Jews of the East: Paris exhibition sheds light on Middle Eastern Jewish history

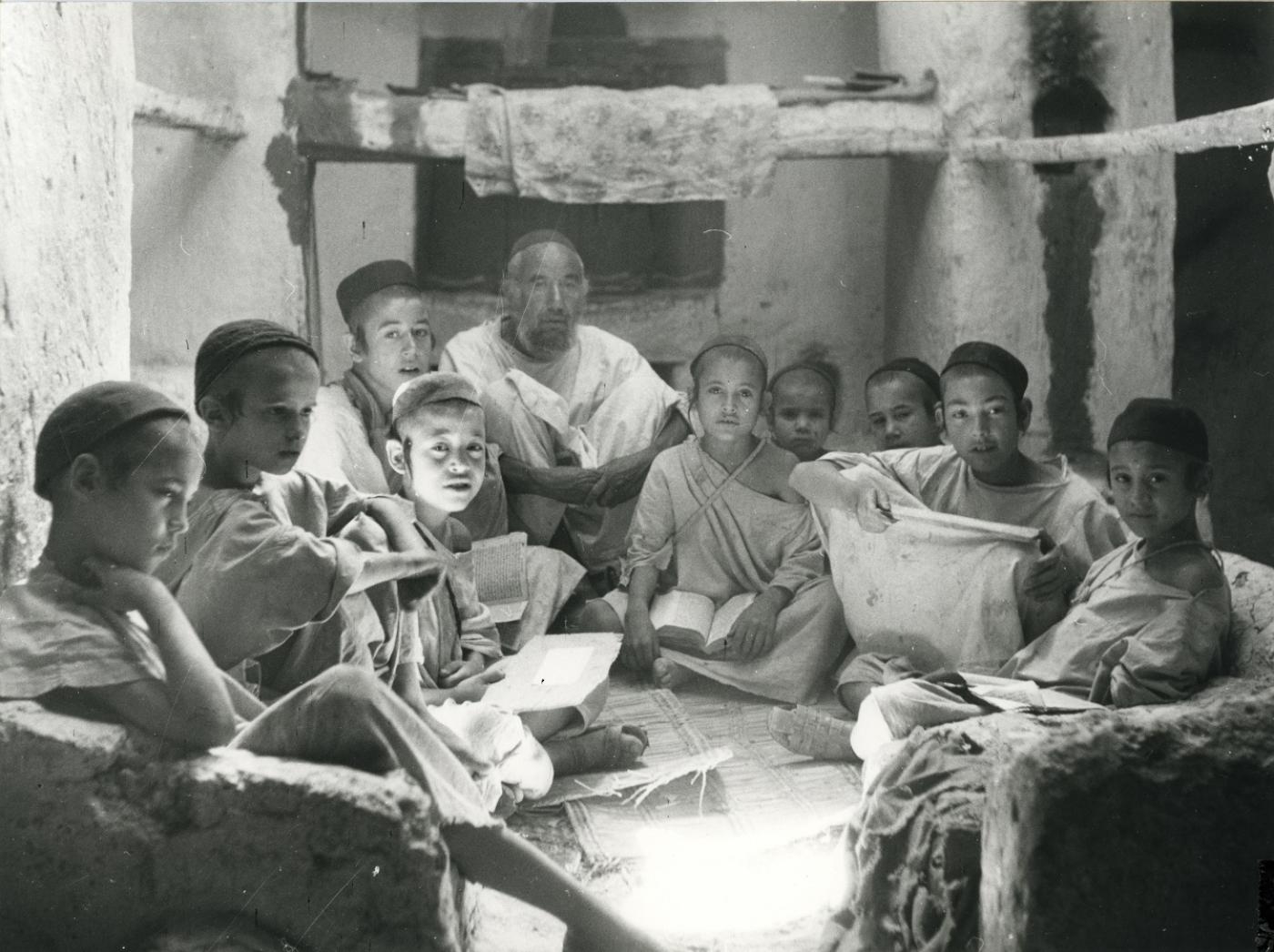

Covering a 2,000-year-long period of Jewish history from antiquity to the present day, the Jews of the East exhibition at the Institute of the Arab World demonstrates the deep history of Jewish communities in the Middle East and North Africa.

The Paris exhibition, which runs until 13 March, presents a story of coexistence between Jewish and Muslim communities, often flourishing (such as during the medieval caliphates in Baghdad, Cairo and Cordoba) and sometimes fraught (under the rule of the Almohad Caliphate in Iberia).

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Historian Benjamin Stora, who curated the exhibition, says the contemporary focus on the Israeli-Palestine conflict and the departures of Jewish communities during the independence of countries like Algeria in 1962 has overshadowed the centuries-old history of Jewish people in Middle Eastern and North African countries.

In an interview with Middle East Eye, Stora discussed the motivations behind the exhibition and his hope that it can spark new dialogue between Muslim and Jewish communities about their shared history.

Middle East Eye: You deplore the fact that so little is known of Jewish history in the Middle East and North Africa. What can this lack of knowledge be attributed to?

Benjamin Stora: By focusing exclusively on the closing stages of Jewish history in the East, on the departures, exiles, and conflicts, we are basically refusing to see it as part of a much larger history comprised of thousands of years of Jewish and Muslim coexistence.

The fact is, the clamour of immediacy tends to hold sway over the recounting of history today, with the events of the more distant past being swept aside, one after the other. Why did Middle Eastern and North African Jewish history fall into oblivion after independence, that is the question we need to ask ourselves. But to understand the history of the ancient Jewish presence across the Middle East and North Africa, we need to re-address the past.

The most pressing challenge colonised nations faced at independence was the building of a consistent national narrative. Lost sovereignty needed to be reclaimed. The problem of minorities, as well as issues like diversity and plurality, would come later, in due course.

MEE: Middle Eastern and North African Jewish history was not passed on in former colonising countries either. This is the case in France, for example, where hundreds of thousands of Jews emigrated after former French colonies gained independence in the 1950s and 1960s. What happened?

BS: This lack of inquiry into the Jewish exoduses from the former colonies of North Africa and the Middle East goes hand in hand with the silence surrounding the history of colonisation itself. It was only two or even three generations later that the reasons for the departures, expulsions and migrations began to be addressed.

In the 2000s, younger generations of Jews began to question this missing link. The historical narrative of the Jews descended from Arab and Muslim nations was at once conspicuously absent and present in the minds of second and third generation Jews, who felt a need to reconnect with a greater, common heritage.

Though older members of the Jewish community in France often spoke Arabic and listened to Arabic music, little was known about the myriad puzzle pieces comprising their past.

When teaching classes on the history of North Africa at Inalco [National Institute for Oriental Languages and Civilizations in Paris, France], this lack of transmission was obvious to me. Students repeatedly asked about the motives and circumstances surrounding the Jewish exoduses from the Arab world.

This younger generation of Jews knew that their history was marked by their eastern heritage, but they didn’t know how or why; owing perhaps to the fact that it had been confused with that of the the Pieds-Noirs [the people of French and other European origin who were born in Algeria]. But deep down, they knew well they had different customs, ways of speaking, and so forth.

MEE: With [the late academic] Abdelwahab Meddeb, you published the encyclopaedia A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations: From the Origins to the Present Day. What kind of impact did the book have?

BS: The book sparked a great deal of interest among Jewish and Muslim communities alike. It was a runaway sales success and prompted a series of conferences. Abdelwahab Meddeb and I spent a year travelling around France, Algeria and Morocco, where we were greeted by sold-out venues. The exhibition at the IMA has also been drawing large crowds since its inauguration.

Young people within the Jewish community who have never lived in Arab countries are thrilled to discover their age-old rich heritage, marked by such learned figures as Moses Maimonides (the Sephardic Jewish philosopher and scientist, who was personal physician to Saladin).

The exhibition is also a testament to the ancient Jewish presence across the Arab and Muslim world, with incredible artefacts from the Roman Empire, such as stones with Hebraic inscriptions brought back from the Roman ruins of Volubilis, in Morocco, and the reconstruction of the ancient Dura-Europos synagogue in Syria, one of the oldest synagogues in the world.

Lastly, it evokes the shared history among Muslims and Jews, although there were notable periods of conflict, including (during) the Almohad Caliphate. The opposite was true during the Ottoman Empire when Jewish communities flourished.

MEE: The example of Maimonides and others highlight the intersecting worlds of Jewish and Muslim communities. The exhibition also traces major periods of tolerance and integration. But these have been obscured by darker narratives of division and conflict. This is particularly true in Algeria. Why?

BS: The case of Algeria is very specific. Algeria was administered as an integral part of France from the first days of colonisation, but the Cremieux Decree in 1870 granted French citizenship to Algerian Jews, which led to their rapidly assimilating and embracing French culture, unlike the Jews of Morocco and Tunisia.

This special status led them to gradually abandon the Arabic language. When the Algerian war broke out in 1954, the Jews of Algeria had already been French for six generations. Though the efforts to differentiate them had succeeded, it was a painful separation, even for Algerian Muslims. I got a sense of this when I returned to Constantine, where I encountered Algerians of my generation who blamed the Jews for having left.

MEE: Your recent graphic novel recounted the journey of the Jews of Algeria, from their arrival with the Phoenicians until their departure in 1962 and was inspired by your own family story. Is that account a way of addressing a certain feeling of uprootedness?

BS: The comic book is an adaptation of my book Les Cles Retrouvees, which recounts my childhood in Constantine during the Algerian War of Independence [1954-62]. By using images, I wanted to impart to younger readers my experience of a world where Jews and Muslims lived together, side by side, even during the war.

The book also aims to help lessen the burden of those who remember, who imagine they are the only ones to have a humane, multicultural vision of the world. Therefore, it does perhaps address a certain sense of uprootedness.

MEE: Has the fall-out of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict permanently undermined the revival of the collective memory of the Jews of the East?

BS: The thread of culture, knowledge, and learning needs to be maintained, regardless of whether the political issues are resolved. If the thread is broken, barbarism and obscurantism will prevail and, ultimately, the resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict will be obstructed for good.

The fact is, an ancient Jewish-Muslim heritage exists, a history wrought at times with great difficulty but that deserves nonetheless to be rediscovered.

For it is through this shared historical prism dating back some 1,500 years that we can hope to forge a new identity - a complex, multifaceted identity that cannot be reduced to a standardised narrative.

The article is an abridged version of a story that was originally published by Middle East Eye's French website. Questions and answers have been edited for clarity and brevity

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.