Reviving the forgotten sounds of Lebanese folk legend Roger Fakhr

Lebanese singer-songwriter Roger Fakhr grew up within Beirut’s lively 1960s alternative music scene. Starting out with a high-school cover band, he was inspired to pick up the guitar and start writing his own compositions when a schoolteacher played Bob Dylan’s songs on the guitar to him.

After clashing with his parents over his choice to become a musician, he left the family home aged 17 and spent a few years walking across Lebanon with his guitar, learning from musicians he met along the way.

"Wherever there was music, I would go and take my guitar with me. I would try to be with folks who played better than I did, so that I could progress," says Fakhr, speaking to MEE over the phone from his home in San Francisco Bay in the United States.

"I would walk all across Lebanon, north to south, east to west… anywhere. I would walk the whole day, get to a village and if I found somebody, then I would stay for the night, living in tents. Lebanon, in those days, my God, it was incredible."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

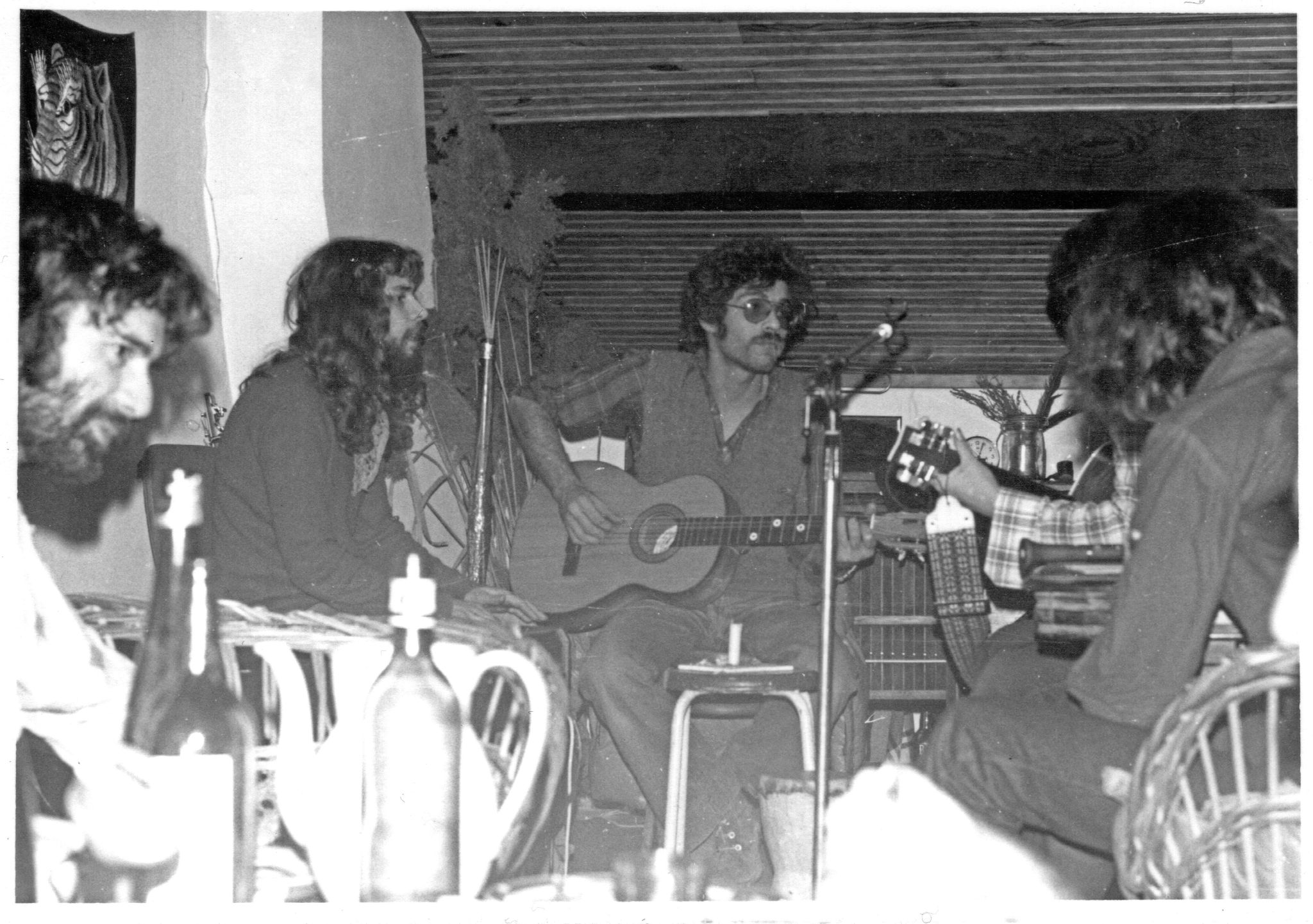

In the early 1970s, he immersed himself in Beirut’s live music community, performing with bands such as The Challengers and The Chargers in Hamra hotels and summer resorts in the Lebanese mountains, and going on to record his own melancholic acid-folk songs solo.

During the war years, before he emigrated to the United States over 40 years ago, Fakhr worked with the likes of Lebanese composer Ziad Rahbani, formed a close musical collaboration with guitarist and composer Issam Hajali and was even asked to join the orchestra of the iconic singer Fairouz for her multi-city tour across the US and Canada in 1981.

Outside the small scene of musicians with whom he worked and performed with in the 1970s, Fakhri's name was largely unknown until recently, left out of Lebanon’s musical heritage

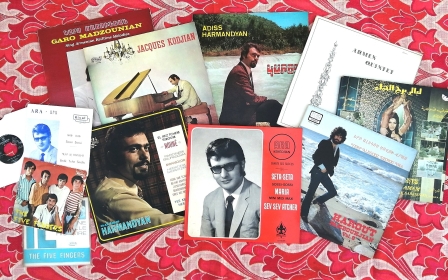

But outside the small scene of musicians with whom he worked and performed with in the 1970s – and a couple of composition and lyric credits on songs by Lebanese singers like Sammy Clarke – his name was largely unknown until recently, left out of Lebanon’s musical heritage.

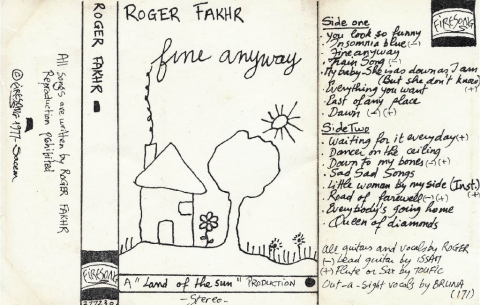

Now, Fakhr’s obscure 1970s album Fine Anyway has been brought to light with a vinyl and digital re-release by Habibi Funk, the Berlin-based record label focused on reissues of music from the Arabic-speaking world.

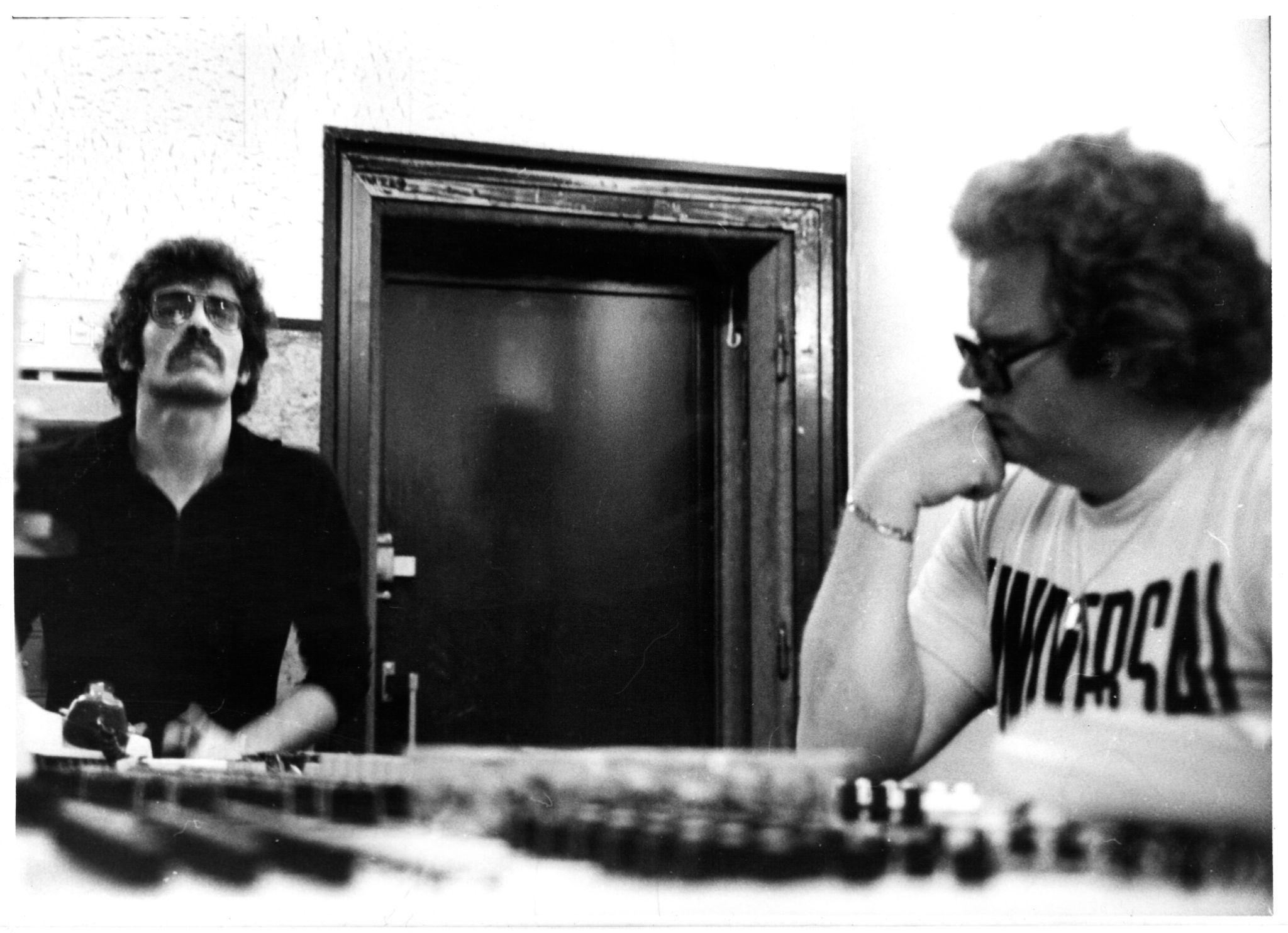

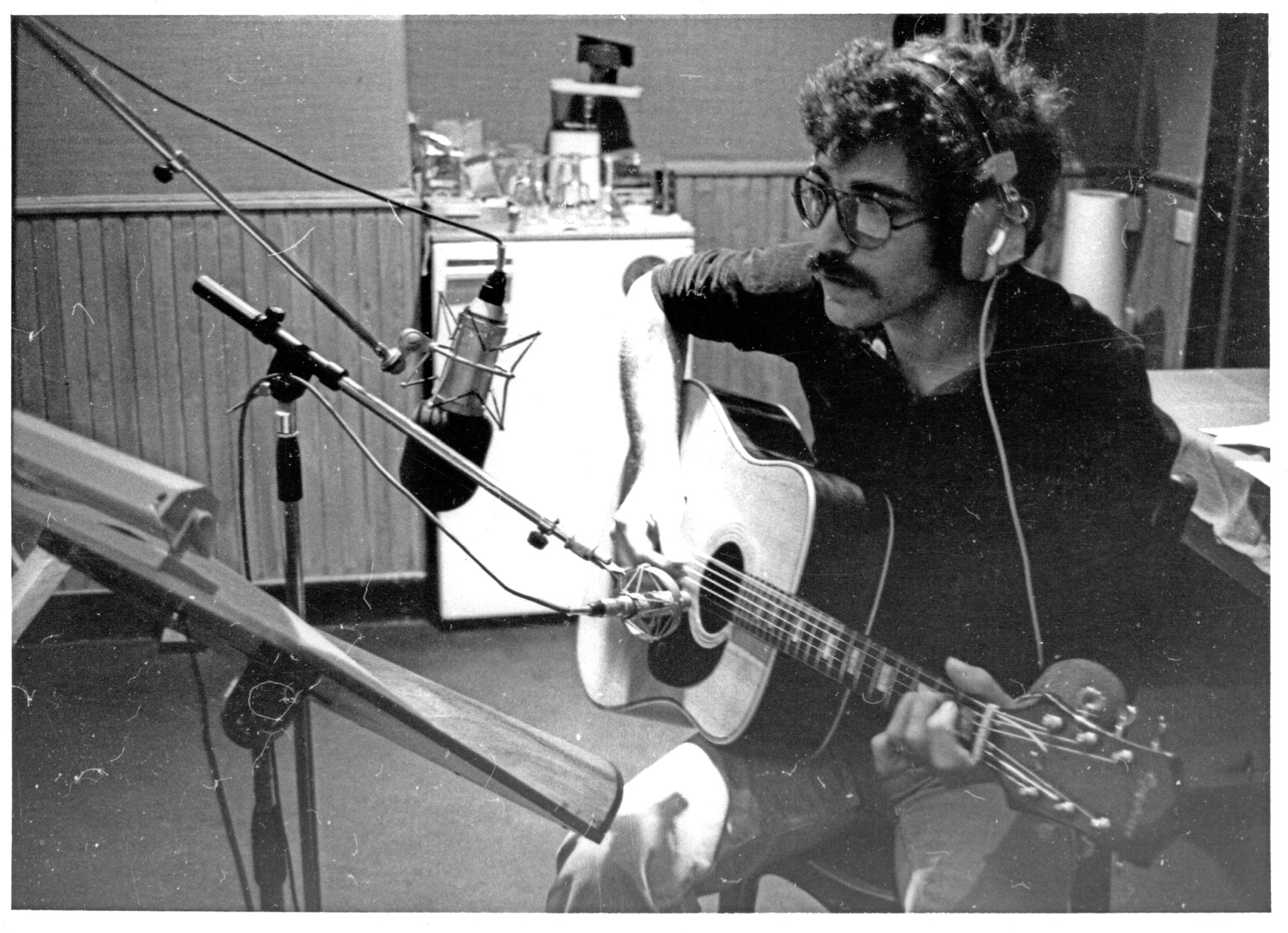

Originally self-released in Beirut in 1977 on a tiny run of 200 cassette tapes, which Fakhr hand-copied and drew the artwork on each cover himself, the album was recorded in a single day’s session in Polysound, the recording studio of Lebanon’s most prolific sound engineer, Nabil Mumtaz.

"We all knew the songs well, but we spent the night before, until 2 or 3am, making arrangements. We never rehearsed," Fakhr recalls.

"We got to the studio and we recorded everything in one day – we only had about 10 hours in the studio altogether. The next day I had two hours in the studio with Nabil Mumtaz to mix it – he said, 'leave it to me' and really did some magic. Mumtaz was a genius – the way that he recorded."

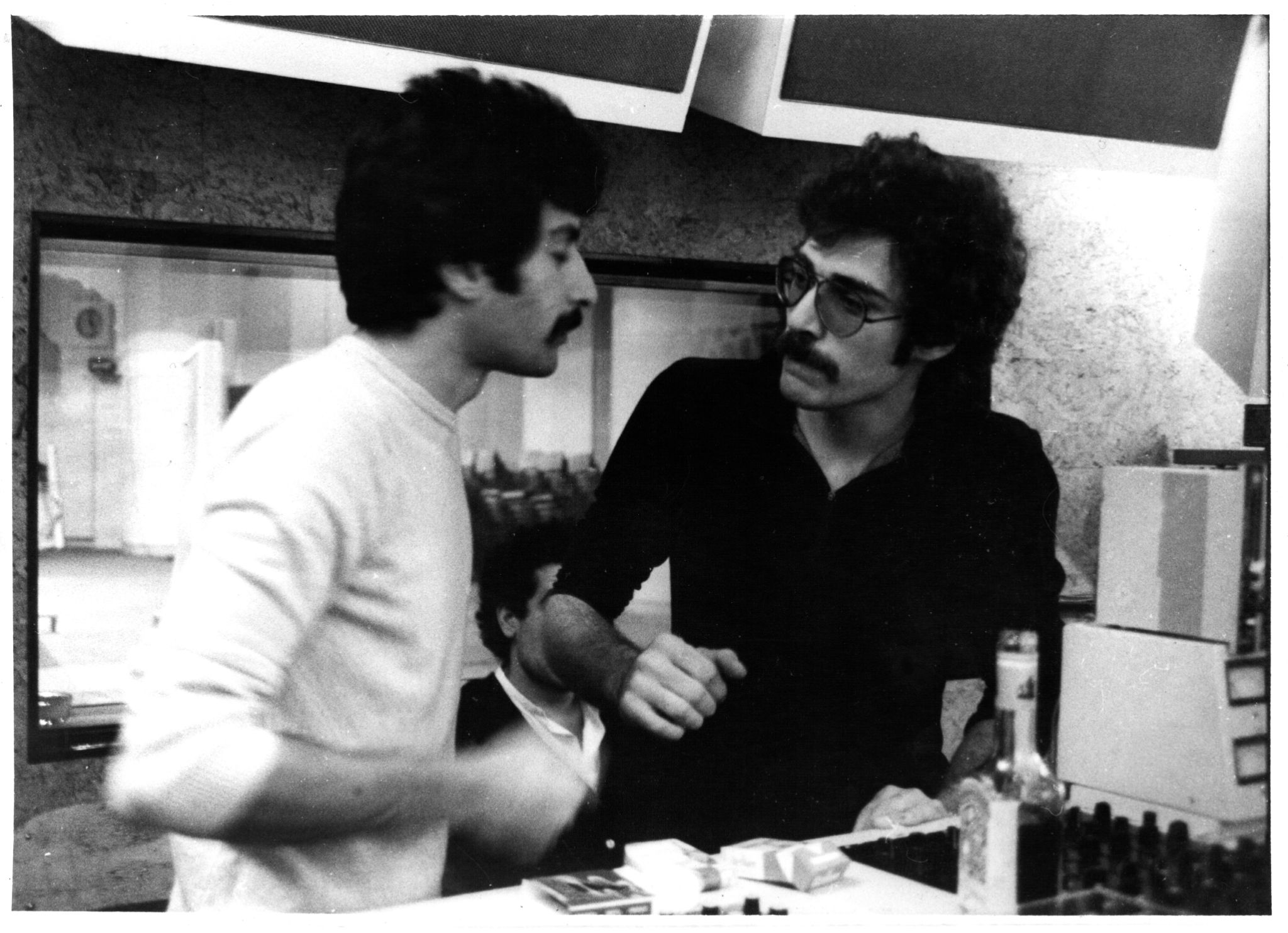

The re-release comes with an eight-page booklet, illustrated with black-and-white photos of Fakhr and friends in the recording studio and the hand-drawn cover of the original cassette release of Fine Anyway.

Accompanying Fakhr on the songs are some of the singer-songwriter’s tightly knit group of musician friends from Beirut: Toufic Farroukh, now an acclaimed jazz saxophonist and composer who teaches at the CRR de Paris; Hajali ,who founded the pioneering Oriental Jazz-fusion band Ferkat Al Ard in the same period; and Bruna Maria, a singer who was also Fakhr’s girlfriend at the time and the muse for much of his songwriting.

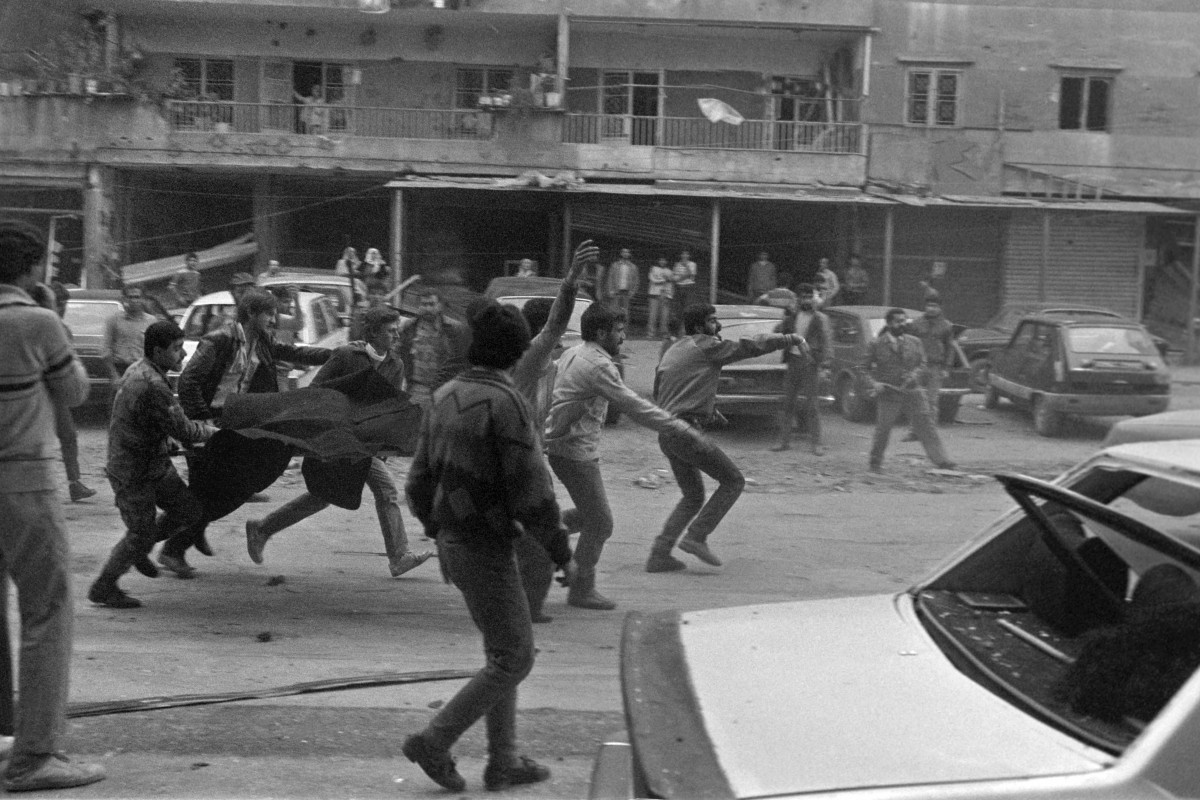

Released a few years into the Lebanese Civil War, the album almost disappeared into the depths of time; with all 200 cassette copies of the release, as well as the master recordings, lost. Fakhr had only managed to distribute a few copies among friends when the Lebanese capital was subjected to a particularly intense period of bombing.

Though he never managed to track down any of those original albums, a friend of his had kept a copy of the cassette and so the original recordings were salvaged. Along with 11 songs from the album, Habibi Funk’s re-issue of Fine Anyway, the 16th release from the label, features seven previously unreleased tracks from other recording sessions in the 1970s – including a couple of songs recorded in Paris with Fakhr’s close friend Raymond Sabbah, a Lebanese musician and sound engineer.

Jannis Sturtz, the founder of the Habibi Funk label, first heard about Fakhr while working on a re-release of Hajali’s debut 1977 release Mouasalat Ila Jacad El Ard, which the singer-songwriter collaborated on while the two of them were in Paris together, having both fled the civil war in Lebanon.

Although Fakhr was initially not interested in re-releasing Fine Anyway – feeling it was incomplete, given the rushed circumstances under which it was recorded – he contributed two tracks to the label’s fundraising compilation following the Beirut Port Explosion in 2020, and eventually came around to the idea.

'Friends and musicians were in and out at all times and music was playing non-stop'

- Roger Fakhr, Lebanese musician

Like all Lebanese artists of his generation, his career was undeniably marked by the civil war. Between 1976 and 1977, escaping the worst periods of fighting in Beirut, he lived on and off in Paris where he used to make money playing on the metro.

But he continued returning to Lebanon to join his musical companions. In the late 1970s, Fakhr moved into his family’s large apartment in Qantari district in West Beirut and it became a kind of artist’s house with musician friends moving in. That creative environment helped to push his music further.

“I confined myself with musician friends, most notably Issam Hajali, Toufic Farroukh, Ibrahim Jaber and Raymond Sabbah,” writes Fakhr in the sleevenotes.

“This was the beginning of a few years of creative heaven. I call these days the ‘Qantari Daze’. Friends and musicians were in and out at all times and music was playing non-stop.”

Though live gigs were scarce, the musicians formed a band and had a six nights a week residency at Hamra restaurant Pizza & Vino, with Ziad Rahbani occasionally joining them, and Fakhr also organised a couple of successful shows in the West Hall of the American University of Beirut, a popular venue for concerts during the war.

Fakhr later spent six months touring Norway with a Top 40 band before he left to go to the United States.

The album is testament to the diversity of Beirut’s music scene in the 1960s and 1970s that saw a whole host of musical influences wash over the city, from beat, rock and folk to jazz and Oriental music.

“Beirut’s music scene was extraordinary. Lebanon was very rich culturally and we received music from all over the place,” says Fakhr. “[The radio DJ] Joe Rihan introduced us to a lot of music from the UK and US, names you’d never even heard of. We all waited for his show on Saturday evenings.

"We had a lot of artists visiting Beirut and an amazing live scene with so many bands. And then you had Arabic music all over the place – Fairouz, the Rahbanis, Sabah, Oum Kaltoum, Wadih El Safih – playing in the taxis, restaurants and on the street. You were exposed to everything.”

In the early 1960s, the Beatles were a “big inspiration” on Fakhr and his friends. When they couldn’t find the records themselves, they got their hands on songbooks and learnt their chords directly.

It was the records of American singer-songwriter James Taylor, though, that left the biggest impact on Fakhr musically: “I was flabbergasted. I heard this lonely voice with the guitar, and I said that’s it… I’m going to be a guy with his guitar and write songs like this. This guy really spoke to me,” Fakhr tells MEE.

Zen in the midst of confusion

Connected to the counterculture hippy movement of the 1960s and 1970s, Fine Anyway is a beautiful, introspective, psychedelic-tinged folk album, taking in elements of blues, country, rock, soul and pop, with poetic lyrics sung in English about travel, Zen in the midst of confusion, love, drinking, broken dreams and boredom.

The album could easily have come out of the folk scene that swept across the UK and America in the same era, with a similar sensibility to artists like Donovan, Shawn Phillips, Nick Drake, as well as, of course, James Taylor, and other more obscure psychedelic-folk artists.

There are only a few hints that the album came out of Lebanon – a looping maqam melody (a type of improvised Arabic melody) on the impactful song Sitting in the Sun and a few lines in Arabic on Keep Going, which ends with the sounds of a bomb siren and gunfire.

Fakhr’s softly sung vocals, poignant storytelling and caressing compositions on guitar creates a certain immersive atmosphere across the whole album, particularly the 11 tracks from the Beirut recording session. The intimate compositions were likely further accentuated by his isolation during wartime.

“The bombing was non-stop and the nature of the youth around me changed. People who were my age, most of them were proud that they went downtown and carried a weapon and started shooting,” Fakhr says.

'The bombing was non stop ... so I confined myself a lot and played guitar alone… did a lot of writing'

- Roger Fakhr, Lebanese musician

“I thought, you know, I can’t relate to this. I played marbles with these guys; I was with Issam joking the other day… you want me to go down and shoot at people because they’re Muslim? It doesn’t make any sense. So I confined myself a lot and played guitar alone… did a lot of writing.”

Opening the album, is the track Lady Rain, a beautifully reflective folk song with lyrics that contemplate the changing of the seasons from winter to spring, female harmony and mystical flute melody lines. The recording was taken from the 1975 LP Toute La Ville Chante (All the City Sings), a compilation of songs from a songwriting competition, which Fakhr won.

Lady Rain sparked the interest of a major label in Paris, CBS Records, but when they started making demands to repackage the songs into something else – wanting French lyrics, and to bring in their own producer, arranger and songwriter – Fakhr refused and the deal fell through.

Title track Fine Anyway is a mesmerising acoustic folk song with spiralling chords and vocals – one of the highlights on the album. Songs such as Waiting for it Everyday, Sad Sad Songs and My Baby, She Is As Down As I Am, wander more into acid folk territory. And there are touches of blues in tracks like Express Line and the Beatles in Insomnia Blue, a jangly folk song with harmonised vocals.

Towards the end of the album, there’s a noticeable shift in style with the final four tracks recorded in a studio in Paris in 1978 with a full backing band of drums, bass and electric piano. Reminiscent of Steely Dan, The Wizard – which reflects on the empty streets of Lebanon in the civil war – Had to Come Back Wet, Gone Away Again and the stunning Sometimes You Feel Bad, a digital bonus on the album, are funkier pop-rock songs with a faster beat and groovy bassline.

The album isn’t without its imperfections – due to the difficulty of raising funds, each recording session in Beirut and Paris was done in just one day with no time to return to the studio to fix mistakes. On a couple of the tracks, such as My Baby She Is As Down As I Am, Farrouk’s flute was “rendered untuneable, because someone sat on it in the studio,” Fakhr writes in the album’s sleevenotes.

And the singer-songwriter believes the songs recorded in Paris were “too mechanical” given the musicians they hired only had half a day to rehearse the songs. But because of those flaws, there’s a certain rawness and charm to the album.

Still, Fine Anyway has clearly resonated with people – the album sold out of its initial vinyl run, with a second pressing in the works and the re-release has allowed Fakhr’s music to travel beyond a small scene of musicians in 1970s Beirut, to the outside world.

Fakhr, who continues writing new music until today, says he would love the chance to rework the songs: "I would like to add colour to them. We never really showed what we could do. It was always done very quickly – it was always drafts and demo tapes. And of course, I’ve changed over the years and hear the songs in a different way now," he says.

"But by the time I do it the way I want to, I will have gone somewhere else in my head.’

'Fine Anyway' is available from Habibi Funk

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.