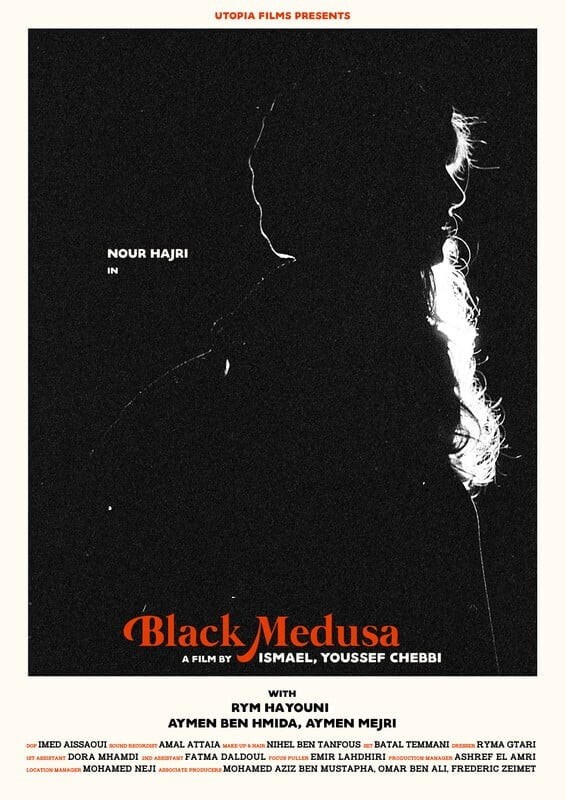

Black Medusa: Will its brutal heroine change North African cinema?

A striking feature debut from Tunisian pair Youssef Chebbi and Ismael is showing the way forward for one of the most worn-out narratives in Middle Eastern cinema, that of the oppressed Arab woman.

Black Medusa is an unflinching work that makes its mark not only with formal boldness but in its genuinely reformist politics.

It opens with a woman sat alone in a bustling bar. She’s young, mysterious looking and undeniably attractive. Her face is stoic, teeming with steely determination but largely undecipherable. Her eyes meets those of a random man. Her look, he promptly deduces, is an invitation to try his luck. The man is inebriated and boasts that he has lost control. She’s indifferent, sober and fully in control.

When they reach his place, he falls on his face unconscious. The woman feels her way around the apartment until she finds a broomstick and starts to rape him, her exultance visible.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

An impressionistic revenge fable gorgeously shot in black and white, Black Medusa is an angry shriek; a brazenly amoral meditation on violence and the righteousness of retribution, and a moody panorama of a lawless Tunisian capital.

With a cryptic narrative that avoids psychological tropes, the feature is a much-needed upheaval of long-held North African narratives on women’s subjugation and the patriarchy.

What makes it distinct is how it breaks free from the "victimised woman" narrative that has dominated North African cinema, giving the female protagonist agency without judging her. In doing so, the directors acknowledge they cannot comprehend the trauma their heroine has endured that results in her using violence as a coping mechanism.

After premiering earlier this year at the Rotterdam Film Festival, it screens at Turkey’s Malatya Film Fest from 10-14 December. It has also been acquired by arthouse streaming service Mubi.

Debt to Abel Ferrara

In her second feature film, Nour Hajri (The Scarecrows) is Nada, an introverted deaf and mute online editor with no visible friends or family. Every night, she allows men to believe they can have her, before she inflicts acts of violence upon them.

Unfolding over nine nights, Chebbi and Ismael's drama doesn’t divulge the motivations behind Nada’s vengeful streak. A sole flashback in the woods implies that she may have been assaulted by a faceless ex-lover, but this suggestion remains hazy, at best.

With minimal dialogue throughout, Nada becomes an empty vessel for the men’s vanities; for their self-centredness, their seedy desires, their pettiness. One divorcee claims he never attacked his wife, but his admission that he did threaten to kill her makes it clear he probably did. Another man pounces on Nada when she doesn’t respond to his advances.

The violence Nada enacts swiftly spirals into murder - a deed she discovers to be quite effortless, if not as gratifying or thrilling. Perhaps her biggest realisation is that she can commit murders without any remorse.

As bloodlust becomes her raison d'etre, she finds respite with Noura (Rym Hayouni), her Algerian colleague and the sole empathetic figure, offering disarming compassion and warmth to the weary, distrustful Nada. But it is only a palliative, for the road Nada has taken has no point of return.

Black Medusa is inspired by Abel Ferrara’s 1981 cult classic Ms .45, about a mute New Yorker seamstress who, after being raped and attacked twice in a single day, embarks on a murder spree, killing random men every night.

Ferrara’s controversial body of work could be summed up as lengthy exploration of the relationship between violence, power and redemption, all filtered from an abidingly Catholic prism similar to some degrees to Taxi Driver writer Paul Schrader.

At the time, Ms. 45 was a revelation: a shock exploitation thriller that places a woman at the centre of the popular, male-dominated vengeance sub-genre of the 1970s. Its predecessor, Meir Zarchi’s much-banned I Spit on Your Grave (1978), also featured a woman vigilante hell-bent on annihilating her rapists.

But Ms .45 was more subversive and more complex in its exploration of the relationship between violence and sex, as well as more unapologetic about its heroine’s lack of motivation for murdering the men who may or may not be blameless. Its influence can be traced to 2007’s The Brave One starring Jodie Foster and Emerald Fennell’s Promising Young Woman, winner earlier this year for an Oscar for best original screenplay.

Black Medusa adopts the Ms .45 premise but goes into thornier, more abstract realms. Its subtle eroticism, broodiness and refusal to make its influences clear are more in line, however, with Brian De Palma’s Dressed to Kill (1980) and Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin (2013), starring Scarlett Johansson.

The birth of Black Medusa

The film was conceived five years ago, when Chebbi suggested to Ismael - his co-director on the feature documentary Babylon (2012) - that they remake Ms .45 in Tunisia, the Arab country that has made the most advances in women’s rights in North Africa. Ismael confessed that he was neither familiar with the film nor a fan of Ferrara. “I honestly wasn’t very interested in the prospect of remaking Ms .45,” he told Middle East Eye.

The pair met again in 2019 and discussed the idea further. Soon, Ismael started to piece together specific scenes in his head. "For me, the origins of film projects are never rooted in specific narratives or themes or ideas. They always spring out of particular images, and this is how Black Medusa was born.”

For their debut feature, Chebbi and Ismael wanted to sidestep the usual route of international co-productions and script development labs, opting instead to self-finance their small-budget project and shoot it quickly.

After one month of discussion and a couple of weeks' writing, the screenplay was ready. Two months of pre-production and 12 days of shooting later, the film was almost ready. This rare freedom is what allowed the pair to realise their vision.

Although Black Medusa does share some similarities with Ferrara's film, Ismael sees it as the opposite of Ms. 45 in characterisation, and distinct from the latter’s overly Catholic resolution.

“Thana, the heroine of Ms. 45, starts off as being vulnerable and lonely, but gradually grows stronger, finding self-empowerment through the murders,” he said. “Nada is the polar opposite. She’s very well organised at first, in full control of her ritualised actions. Her veneer gradually starts to crack, as she begins to feel with Noura the kind of genuine and profound emotions she has not experienced before.

“Another distinction is how Ferrara at the end chooses to punish Thana, seeing it as the sole means for her absolution. That’s not the case with Nada.”

With its cryptic narrative, Black Medusa offers a radically revisionist take on the victimised Arab woman battling, mostly in vain, the unconquerable patriarchy.

Here a female protagonist is given agency. The film-makers also refuse to judge her, acknowledging that they cannot comprehend the trauma their heroine has endured, and which results in her using violence as a coping mechanism.

Black Medusa's politics are more in line with commercial films of the 1980s and 1990s which centred on neglected Egyptian women. These were fronted by a group of the country’s biggest female film stars at the time – including Nadia El Gendy, Nabila Ebeid and Naglaa Fathi – and included the likes of The Lost One (El Da'eaa- 1986), The Woman and the Cleaver (Al-Mara’a wa Al-Satour, 1996), The Iron Woman (El-Maraa Hadideeya, 1987), about heroines taking it upon themselves to avenge the men who had wronged them.

Like Nada, these Egyptian characters sidestepped the authorities to take the law into their own hands. Unabashed about using their sexuality to achieve their goals, they took a vigilante path that allowed them to assert their individuality and feminism away from an indifferent system.

But Ismael is keen to draw a contrast between Black Medusa and these earlier works. “These [North African films] may seem to empower women, but they do it through a bourgeoisie or capitalist framework. Nada lies outside these social, moral or historical frameworks.”

Chebbi and Ismael put Nada in full control of her own destiny. Nada assaults these men not because she’s compelled to, not out of any ethical or ideological or even feminist duties: she does it simply because she enjoys it.

The story does not delve into the character's psychological motivations but instead works on a symbolic level. Its one-dimensional, villainous depiction of her male targets is therefore justified.

“She’s an editor, she assembles images together," says Ismael. "She mixes and makes up her own reality. She’s honest about her own twisted sexual desires. She’s content with lying in the margins of society… of reality, even.”

The slippery narrative, the vagueness of motivations, the clashing sentiments Nada endures… these are not just part of the film’s formal design that stand in contrast to the narratives outlined above; collectively, these elements represent a philosophical decision reflecting the film-makers’ recognition that as men, they can neither fully comprehend nor accurately convey the harrowing traumas women like Nada are forced to live with.

'There are a lot of male directors everywhere who are doing these pseudo-feminist movies that are in fact very patriarchal'

- Ismael, co-director

“Naturally, I’ll never know what being a woman means or feels. I can never put myself inside the woman’s shoes. It would be conceited to claim otherwise. There are a lot of male directors everywhere who are doing these pseudo-feminist movies that are in fact very patriarchal. We were very conscious of that. Psychologising the female experience is synonymous with moralisation for us,” Ismael said.

“We also didn’t want to fall in the trap of presenting sexual trauma and being obliged to explore it in literal terms. What happens to Nada can be interpreted in different ways, but I don’t personally see it as rape. When directing Hajri, we even told her that the character could be a virgin. She is clearly suffering from a grave trauma, but it may not be sexual.”

There’s a palpable unease with which Nada interacts with the world through her body. Only when she inflicts violence on men can she attain the agency of her body. The role of violence in Black Medusa is thus multi-layered.

For Nada, there’s a cathartic effect when she first inflicts pain on the men but that proves to be short-lived, and is overtaken by monotony. The use of violence, choreographed without a hint of sensationalism, is transformed from an instrument of cleansing to repetitive work; an increasingly meaningless yet devouring addiction.

Tunis is another principal character in the film. Shown mostly in a composite series of spare nocturnal panoramas, the Tunisian capital emerges as a discordant urban wasteland – a series of scattered facades as chaotically structured as the lives of the people who inhabit them.

The city, in the imagination of Ismael and Chebbi, is a depraved jungle, abandoned by law and scorned by its disenchanted denizens. The methodical homicidal measures Nada follows stand as a reaction towards the disorderliness of her city.

Nada in Spanish means nothing, and at the end of Black Medusa this enigmatic heroine evolves into an empty vessel through whom the audience project their own traumas, fears, perversions, anger and loss. Nada is the avenging angel, the impenitent killer, the anguished wanderer - call her anything but a victim.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.