Drones, dogs and fences: The security ‘shepherds’ guarding Europe's borders

BUDAPEST, Hungary - "They do have a certain scent, the illegals. They may not have had a wash for a while, or they may have been sitting round a campfire for days on end," explains Collin Singer, the managing director of WagTail, which supplies "body detection dogs" to the UK Home Office.

The dogs are stationed at UK border posts on the French side of the English Channel, and tasked with sniffing out people intent on reaching the UK undocumented. So far they have detected "thousands of illegal immigrants", Singer says, although he adds that he isn’t allowed to say exactly how many.

WagTail is one of several businesses advertising their services at the Borderpol Global Forum, a conference held at a hotel in the Hungarian capital Budapest earlier this month.

WagTail’s spaniels and Labradors have a tough job competing with the high-tech border control solutions which pepper the trade floor, and the dogs do sometimes get confused, Singer admits.

“How can a dog tell that this person standing by the cab of the truck is okay, but this one hiding under some pallets inside the truck isn't?" he asks, rhetorically.

Thankfully for WagTail, the Home Office believes in the project. "We have a good relationship with Barbara," Singer tells me, smiling broadly in his sharp pin-striped suit.

'We make our own bread in the UK'

"Barbara" is Barbara Wilson, deputy head of the UK border force's "Business Change Projects" division. She was awarded an OBE (Order of the British Empire), one of the UK's highest honours for public service, by the Queen in 2014 for “services to border security”.

WagTail likes Wilson – and Wilson likes them: during their speeches she and a colleague praise the "marvellous" job done by the contractor’s sniffer dogs.

Wilson’s turn at the podium in the conference hall, which occupies half of the exhibition space, is a change in tone from the generally terse presentations that came before, delivered by a parade of men in grey suits.

Her all-black Border Force uniform looks almost glamorous by comparison, its silver epaulettes gleaming. “I do all my own choreography,” she quips as she takes to the stage. She projects a slick video produced by the Home Office, showing border guards dismantling vehicles thought to contain drugs, and pauses at certain points to explain what is on screen.

Wilson’s going for the hard sell – the Home Office is currently advertising training services to other governments, and hopes that the Irish border guards it trained this year will be "the first of many".

“The UK border force considers itself world class in terms of searching,” she says, flicking through photos of the outlandish drugs-smuggling methods her staff have uncovered.

“Bread isn’t always what you think it is,” Wilson warns as she pauses on an image of what looks like standard loaves, but turns out to be hollow doughy shells concealing illegal drugs. “And we make our own bread in the UK, so you don’t need to bring it to us.”

Wilson is followed on the podium by her colleague Rebecca Stevens, who specialises in searching for smuggled people. "The concealments that we are seeing now are becoming far more challenging to detect," she says.

She shows pictures of young people who have curled their bodies around the insides of car engines, or concealed themselves inside car seats, reminiscent of methods used to flee East Germany during the Cold War.

Others who stuffed themselves into suitcases, Stevens says, "gave the French security firm a bit of a fright".

The use of carbon dioxide detection technology means some people are dressing up in scuba gear, she says – some wrap their entire bodies in plastic sheeting to cross the border. “This is obviously very, very dangerous,” Stevens says. “Once they’re wrapped in plastic they haven’t got long before they start getting seriously ill.”

'Market demand' in Middle East

At the end of these presentations, Tony Smith bounds onto the stage. Smith, who holds a CBE (Commander of the British Empire), retired from public service in 2013 after seven months as head of the UK Border Force – he is now deputy director of a private border security consultancy, Fortinus Global. “How brilliant was that eh?” he extols. “UK Border Force.”

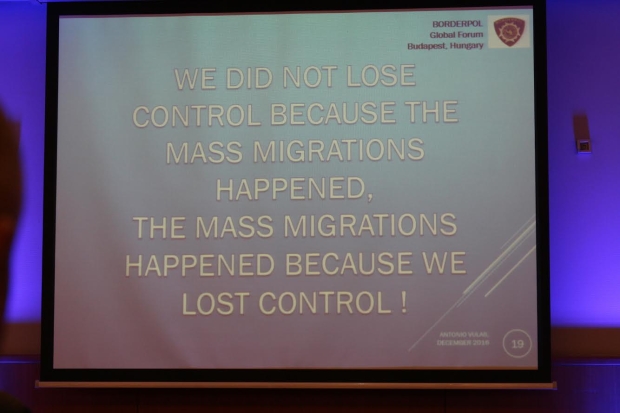

This air of theatricality runs through the whole three-day affair. Speakers use a range of colourful metaphors to describe migration: border guards are “shepherds” protecting ordinary sheep from the wolves who would do them harm; migrants flow across borders like “water in the desert”; they are also, apparently, cancer-like, and there is a “metastasising growth” in the numbers of arrivals. “Detained asylum seekers” and “detained cigarettes” are talked of in the same breath.

An official from the Hungarian interior ministry dons a safety helmet and has a go on one of the Segway scooters on display, doing jerky circles of the carpeted room before climbing off with a look of relief on his face.

At one point a man dressed as Santa Claus approaches the room, and then wanders off again.

READ: 'Muslim' meals could be used to profile passengers, airline tells authorities

Among the companies exhibiting at the conference is one that sells the “prison fence” used to build a new razor-wired frontier between Oman and Yemen. At a stall opposite, the Seven Technologies Group is displaying tracing and tracking devices designed primarily for police but which could, a salesman tells me, “be used in any place you deem fit”.

They also sell thermal imaging cameras “good for use in hot climates” - the company, based in Northern Ireland, has just opened up a new office in Abu Dhabi, and has translated its glossy sales pamphlets into Arabic.

“With everything that’s going on in the region, there’s obviously a lot of market demand,” a representative tells me.

Next door, a group of suited men sell what look like automatic weapons – but turn out to be the sights used to help aim them.

“We sell them to border agencies in the Middle East, where border guarding is a bit different,” one of the salesmen from Schmidt and Bender tells me.

Making the world 'a better place'

Yet despite the sometimes parochial feel of the forum, Smith says he hopes the conference will help make the world "a better place".

He also believes that this is where big border management decisions are made. The event is advertised to industry as a "direct route to senior border security professionals," and promotional material promises exhibitors "unprecedented access to senior figures making serious investment decisions on the future of border security".

“We find that some of the engagement that suppliers have here with border agencies is really helpful,” Smith tells me. "We’re certainly not in the business of becoming a trade fair - but we do encourage collaboration.”

The event is sponsored by Securiport, a US company that makes immigration control systems and biometric technology. They have sponsored this forum for the past three years, and employ a dedicated “conference coordinator”. “We’re family,” the coordinator says of Securiport’s relationship with Borderpol. “We help Borderpol out, and they help us out.”

The head of Securiport, when he takes the floor, has a bouncy energy reminiscent of a preacher. Attila Freska shuns the fixed podium to rove about the front of the room.

After a short tangent to advocate the use of profiling at airports - which, he says, is "very politically incorrect" - Freska moves onto the meat of his presentation: the advantages of Hungarian-style border control, and the technology that can make it happen.

“We recommend that physical barriers, as per the Hungarian example, are effective,” Freska says, in reference to the fences Hungary has erected along its borders with Serbia and Croatia. “But we know that these physical barriers can be breached - this is why thermal imaging and radar systems are necessary. And then of course we have drones.

“These are the solutions - and remember, all these tools are here because we’re shepherds,” he adds.

It’s a vision of border management that is enthusiastically espoused by Smith and the rest of the Borderpol leadership. “It’s well worth your time speaking to people like Attila,” Smith tells the assembled crowd after Freska’s presentation. “The importance of these kinds of technologies cannot be underestimated.”

It seems appropriate that this year’s conference was held in Hungary – a country that last year spent $106m building a fence along its entire 175km border with Serbia - and jointly hosted by the Hungarian interior ministry, which welcomed delegates to a drinks reception at its headquarters on the first night. Budapest is, Smith tells me, Borderpol’s “spiritual home”.

“We’ve always found the Hungarian authorities to be hugely welcoming and supportive of our cause,” he says.

The 'Hungarisation' of border security

That cause, says Martin Lemberg-Pedersen, assistant professor of global refugee studies at Aalborg University, is one that promotes the “Hungarisation” of European borders at the cost of a humanitarian approach to border management – in a year that has seen more people die at European borders than ever before.

The United Nations said this week that 2016 had the “worst annual death toll ever seen” for people dying during attempts to reach Europe, with more than 5,000 people drowning in the Mediterranean - or a daily average of 14 deaths.

READ: 'They started to die together’: Can Egypt protect migrants in 2017?

“The number of deaths at the external European borders has never before been this high – and at the same time, there has never been this much control over those borders,” Lemberg-Pedersen tells me by phone after the conference.

“The Hungarian approach last year was to build a border fence. But a fence is not just a fence – it’s an infrastructure that comes with contracts, which these companies then converge on.

“This Hungarisation of border control in Europe is happening. We're seeing it at the political level as well - but it is also flanked by an infrastructure push. The push towards building walls and fences feeds very well into the framing that these private security companies are eager to promote."

“That's what this kind of conference is all about. It's not surprising that it was sponsored by a private security company - but any notion that it could be a neutral or open conference is impacted by this sponsorship.”

Lemberg-Pedersen says the conference – at which the main sponsor also gave a speech advocating the use of its hardware for border control - also reflects an attempt by industry to militarise national borders, in the face of falling profits in the traditional military sector, by acting at once as advisers and as merchants.

“It's not easy for politicians to distinguish between scientific experts and industry. Companies are selling products at the same time as advising governments on what to buy,” he says, citing the Group of Personalities, a European Commission project that brings together politicians and the heads of military hardware companies like Airbus and BAE Systems to advise the EU on how to spend its defence budget.

READ: Security chiefs use bomb fingerprints to screen refugees

“It's a good position for them to be in,” Lemberg-Pedersen says. “And because of this kind of push, which seeks to link up police and civilian tasks with traditional military tasks, border control has moved from being perceived as a largely civilian issue to become a more militarised one. At the same time this push is supported by large European credit institutions and banks, as it creates a lucrative export market for the European arms industry.

“The idea that we should model our approach on Hungary implies that we shouldn’t talk about things like resettling asylum seekers – instead we should just fortify and militarise the external borders.”

But it’s an approach that isn’t finding a foothold everywhere. The stall-holders for MSA Global, the company behind Oman’s border fence, say they haven’t had many takers at the conference. “I can’t see France building a border fence,” one of their salespeople says. But if Trump keeps his promise to build a “great, great wall", they might get some interest from the US. “You never know,” he ponders.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].