International markets offer ray of hope to beleaguered Tunisia artisans

TUNIS, Tunisia - Fakher Baklouti’s father taught him to work with olive wood as he was growing up outside of Sfax, an industrial city about halfway down Tunisia’s Mediterranean coast. The texture and patterns in the wood appealed to him, and he found it easy to turn into beautiful, artistic products. Now, Baklouti is proud to be a third generation olive wood artisan carrying on a traditional Tunisian craft. “It’s important for me that it’s purely Tunisian,” he said.

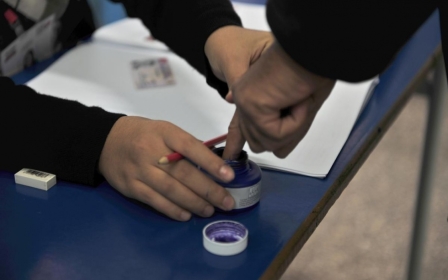

Since the country’s 2011 revolution, Tunisia has experienced a prolonged period of economic malaise that has made life more difficult for Baklouti and other artisans. Tourism has declined, shrinking an important client base, inflation has increased the cost of raw materials and cheap, and smuggled goods from Libya and Algeria have flooded the market.

“It’s been hard to keep up,” Faisel Ben Ghorbel, a silversmith in Tunis’ old city, told MEE. For him, the price of silver per kilogram has risen in the past four years from around 300 Tunisian Dinar ($160) to between 1000 and 1500 ($540 to $816).

“Mainly, what keeps us doing this is the passion,” said Ben Ghorbel, who specialises in making silver goods with traditional designs from Tunisia and Libya’s Jewish communities.

Preservation and opportunity

The challenges facing Tunisian artisans are of great concern to Leila Ben-Gacem, a Tunisian entrepreneur with an interest in historical preservation.

The current economic situation, according to Ben-Gacem, is threatening Tunisia’s heritage. Many artisans have started to work as traders, food sellers or taxi drivers. “If we don’t do something now we might lose a lot of national skills in a few years,” she said.

Ben-Gacem started two social enterprises, Blue Fish and Blue Fish & Bro, to help Tunisian artisans develop their products and connect them with new markets abroad.

Blue Fish organises trainings for artisans and functions on grants from international organisations and, increasingly, the reinvestment of profits from a boutique hotel Ben-Gacem runs in Tunisia’s old city.

Blue Fish & Bro searches for international buyers for artisanal products. The company pays artisans upfront when they receive an order so the artisans have enough cash on hand to buy raw materials, pay labour costs and live. In return, Blue Fish & Bro sells the products at a marked-up price and keeps the profit to cover the costs of operation.

“We are a social enterprise. So, our main goal is to help support the artisans,” explained Nicole LaGrone, an American living in Tunis who works with Ben-Gacem. “But, it’s not an NGO, it’s not a charity. So, we need to make some profit to survive.”

Confronting the challenges

Without support from companies like Blue Fish and Blue Fish & Bro, it would be very difficult for artisans to sell their products abroad, according to Nizar Jouini, a professor of economics at Jendouba University and the Tunis Business School. The challenges exist on several levels.

Most artisans work in the informal economy, which means they cannot directly export their own products. “To move to the formal sector is a risk for them,” Jouini said.

Taking out a loan from a bank to cover the costs of moving to the formal sector is not a viable option. “The macro-banking situation is not stable,” Jouini added. Tunisian banks are relying on the central bank to give them money to stay solvent, but the central bank does not want to lend too much because of inflation, he said.

As a result, it is difficult for individuals and small businesses to get loans. When banks do give loans, “it’s not enough to help”, according to Ben Ghorbel.

Loans from microfinance institutions such as ENDA are another option for artisans that avoid many of the difficulties associated with the formal sector. Since the market for artisanal goods has declined after the revolution, according to Ben-Gacem, many artisans are using microloans to start new businesses instead of continuing to work in their crafts.

“There’s a lot of unwritten laws in exporting and importing,” Ben-Gacem said.

Navigating that without help is nearly impossible, according to Ben Ghorbel, “You need a lot of money,” he added, and connections to obtain the right licenses and push your products through the notoriously corrupt Tunisian customs system.

“I hate to admit it, but it’s because of this complexity that companies like Blue Fish & Bro exist,” Ben-Gacem said. “Otherwise, artisans can export [on their own].”

Need for reform

In order for the Tunisian economic situation to improve overall, which would be the most sustainable solution for artisans, the newly-elected government is going to have to tackle large-scale economic reform, Jouini said. “The Tunisian economy is like a car,” he said. “This is the maximum speed that the car can go. So, we need to change the car.”

Long term economic downturn will fuel political instability, Jouini added. The Tunisian revolution was largely motivated by economic grievances. “The problem is still there. We need to find solutions,” he told MEE.

For Baklouti, the question is not just about economic and political stability. It is also about heritage. He hopes that, if they are interested, his four- and six-year-old daughters will be able to choose to carry on the family tradition of making something authentic and beautiful from Tunisian olive wood.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.