Khaled Said five years on: The state of Egyptian street art

Five years have now passed since the humid night in June 2010 when Egyptian blogger Khaled Said was dragged out of an internet cafe by two police officers and beaten to death in the street just across from his family home.

The grim anniversary was marked by small clusters of protesters who gathered at roadsides holding up small signs with slogans like “Glory to the Martyrs”. Said’s family could not attend a memorial protest in Said’s hometown of Alexandria because the event’s time and location were changed several times to escape police attention.

Five years on from the 28-year-old’s brutal public killing, Egypt’s Interior Ministry has yet to release his death certificate. A lawyer for Said’s family, Mahmoud al-Afifi, said on Saturday that the state’s desire not to disclose his cause of death was behind the years-long delay, which the family intends to challenge in court.

The ministry’s alleged reluctance to release Said’s death certificate has puzzled many in Egypt, especially when campaigners say the cause of his death has been abundantly clear for so long. Almost immediately after his killing, a graphic image began to spread like wildfire on Egyptian social media: Said’s body lying on the metal table of the morgue, his face beaten almost beyond recognition.

This is the image that sparked the rage of millions of ordinary Egyptians, a rage that grew in the months leading up to the revolution of January 2011. It showed, they said, that the security services under President Hosni Mubarak felt empowered to kill in front of a large crowd a man who had recently published a video claiming to show police divvying up the spoils of a drugs bust.

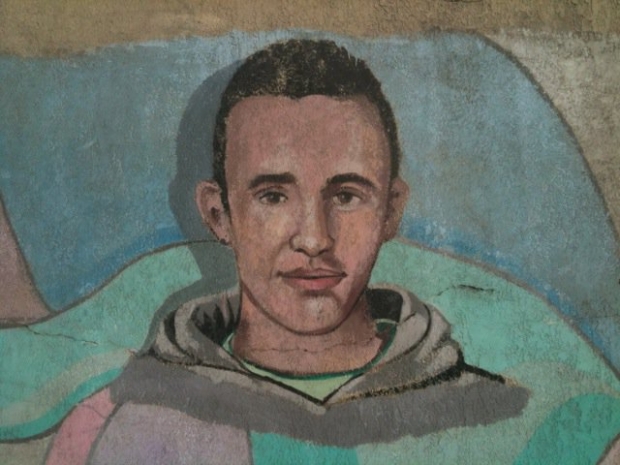

But it was a very different picture of Said that millions of Egyptians saw when they took to the streets in the 18 tumultuous days leading up to Mubarak’s resignation. An image of Said dressed in a plain grey hoodie and wearing a faint smile, a picture based on his passport photograph, became the basis for thousands of multi-coloured murals, graffiti pieces and stencil drawings that sprang up on the walls and pavements of Egypt’s urban landscape around that time.

“Images of Khaled Said were very common just before the January revolution, and during the first year after it,” says Ahmed Nady, an Egyptian illustrator and graphic artist close to the street art scene. “The images appeared mostly in places with some link to the Interior Ministry.”

Said was far from alone in suffering and even dying at the hands of Egypt’s police and security services. But, says Nady, “nobody paid attention to them as they did Khaled Said after the picture of his body in the morgue appeared”.

He was also among the few middle-class Egyptians to be targeted by the state, according to Amro Ali, a PhD student at the University of Sydney who divides his time between Australia and Alexandria.

“You would usually expect this to happen in the slums or the city’s rural outskirts, in prisons or in Islamist strongholds. This, though, happened in a well-heeled neighbourhood. It was highly unusual for someone from the middle class to be brutalised to that extent.”

Said was also remarkable, says Ali, because though he came from a specific sector of society, the secular urban middle class, he did not subscribe to any particular social movement.

Nady reels off a long list of other people, like the Alexandrian Salafi Sayyed Bilal, the senior religious figure Sheikh Ammad Afat and the leftist Coptic Christian Mina Danial, all killed by the security services and all “symbols from each sector of society”.

But Said, unlike the others, “wasn’t affiliated with any political or religious movement: everyone could claim him as their symbol,” says Ali, who comes from the same neighbourhood as Said.

Because of this, says Nady, Said quickly became “a symbol of the victory of the oppressed against despotism”.

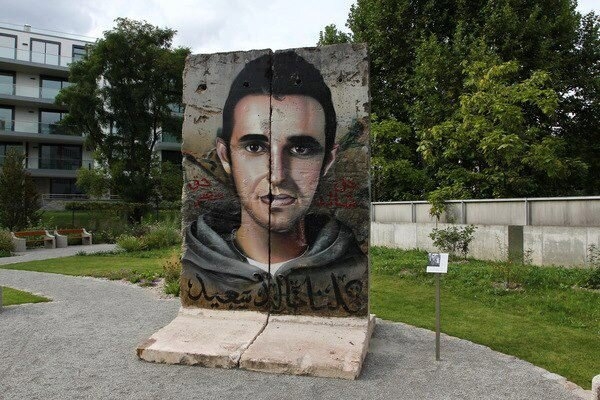

Five years on, though, with two policemen serving ten-year sentences for his murder, Said’s image has all but disappeared from Egypt’s streets and public spaces. The thousands of murals and stencils have gradually been painted over, obliterated either by security services, vandals or activists with other messages to spread. Now, the longest-lasting mural to feature Said’s image is not in Cairo or Alexandria, but in Berlin.

“There are remnants of the graffiti here and there in Egypt,” says Nady. But amid the quicksand of Egypt’s political landscape, street art doesn’t last long.

“There is one mural [of Said] in Alexandria that has survived for about 18 months now. But I don’t expect it to stay much longer,” says Ali.

“He has been forgotten, at least to some extent. A local Salafi recently told me to forget about Khalid,” he says, explaining that the Salafi community was originally “the most sympathetic” to Said’s case, because they had suffered similar abuse for years without attracting nationwide attention.

Part of the reason for Said’s story fading from public view, according to Nady, is that the years since the 2011 uprising have seen “thousands of others” suffer at the hands of the Egyptian security services.

The youth of today, inspired by the same revolutionary ideals as those who rose up against the 30-year rule of former president Hosni Mubarak, have a new set of post-2011 “martyrs” who are adorning the walls.

One figure whose death came close to igniting anger on the same level as that which followed Khaled Said’s killing was Shaimaa Sabbagh, the socialist activist shot dead by police as she went to lay flowers at a memorial for those killed in the January 2011 uprising.

Another native of Alexandria, she is buried in the same cemetery as Said. Like Said’s, her death, also in public and also at the hands of the police, grabbed attention across Egypt and worldwide through a set of graphic images.

“I don’t think people will quickly forget the picture of her falling into her colleague’s arms,” says Ali of the shot that captured Sabbagh’s last moments during the January 2015 protest.

“A lot of pro-regime figures actually attended her funeral,” says Ali. “There was even anger within the Egyptian police force about her killing. She’s a very potent symbol.”

A police lieutenant was sentenced to 15 years in prison on Thursday over her killing.

After her death, even the state-owned daily al-Ahram published a piece criticising the security services and the government of President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. Still, despite the symbolism of her killing during a peaceful memorial protest, Sabbagh’s image did not end up adorning Egypt’s public space. Instead the most prominent mural of the 31-year-old appeared, again, not in Cairo or Alexandria, but in Berlin.

“The current regime does not allow for freedom of expression on the streets of Egypt,” warns Nady. “Doing graffiti has become an adventure so risky that it could lead the artist to lose their life.”

In the immediate aftermath of the 2011 uprising, a string of high-profile street artists were arrested, many of them tried with offences like defacing military institutions and eventually tried before military courts. Now, a year into the presidency of former army general Sisi, the situation has grown even worse, according to Egyptian graffiti artist Sifa Abu al-Abbas, active during the revolution and since.

“The police are now cracking down on street artists, especially when there are few of them,” she told Egyptian news site Tahrir News earlier this year. ”The truth is that everyone is in low spirits at the moment, and while people are being arrested at random under the protest law, it’s not the right time for any steps that might escalate things.”

In this environment, Abbas says, street art has now become sanitised - more about party politics and social issues than the huge challenges facing Egypt’s youth.

“The regime uses graffiti as political propaganda, and shuts young people out of it.”

In the midst of the state’s struggle against an armed insurgency in the country’s remote eastern Sinai province, and with an act of political violence committed on average every 1.5 hours, Nady says the government is now using street art to create an aura of safety and security.

“The government is attempting to sow culture through oppression, as a synonym for stability amidst the fight against terror.”

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.