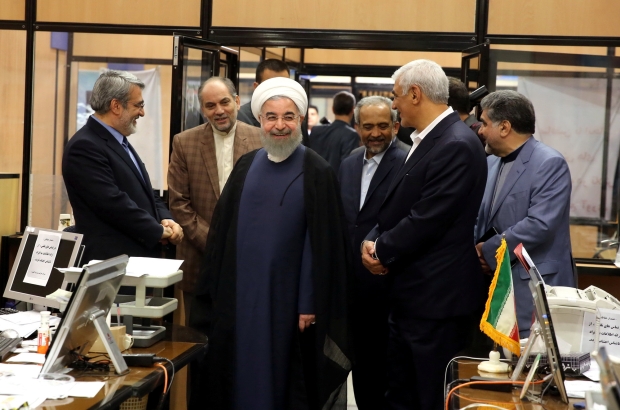

ANALYSIS: Rouhani landslide redraws Iranian political map

Incumbent Hassan Rouhani caused a surprise in the Iranian presidential election by securing just over 23.5 million votes, totalling 57 percent of the tally. While he was the clear favourite throughout the campaign, Rouhani had a late surge in the final phase of the campaign when he deliberately set out to create polarisation by drawing a sharp distinction between "moderates" and "hardliners".

With a turnout of nearly 41 million, just under 74 percent of the electorate, the election is being interpreted as a resounding success for the Iranian political establishment by affirming the public's trust and confidence in the Islamic Republic.

The conservatives may not regain control of the executive branch of government for a generation

Just a couple of days before the elections, the Iranian leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, had called for a high turnout by way of sending a clear message to the country's enemies, notably the United States and Israel.

In view of his incendiary attacks on his main rival, Seyed Ebrahim Raisi, coupled with his big majority, President Rouhani is expected to move nearer to the reformists' camp, thus sharpening the divide between his government and its detractors.

As for the conservatives and the principlists, their loss is considerable and far-reaching, not least in view of their massive mobilisation, particularly in the closing stages of the campaign.

Absent a prolonged period of soul-searching, followed by a recalibration of tactics and messages, the conservatives may not regain control of the executive branch of government for a generation.

Resounding victory

Compared with the 2013 presidential election, Rouhani increased his share of the vote by seven percentage points. This is significant as, historically in the Islamic Republic, the sitting president loses part of his majority as a result of unfulfilled expectations and related issues.

The turnout was also slightly higher than 2013, with Rouhani's centrist-reformist coalition energising voters through scare tactics and polarisation.

By recreating the polarised atmosphere of the disputed 2009 presidential election, albeit under more controlled conditions, Rouhani's campaign team effectively delivered a death blow to the principlists.

The centrist-reformist surge is also reflected in the town hall and village council elections, staged in parallel with the presidential elections, with the reformist "List of Hope" candidates set to dominate Tehran city council.

A principlist with an eccentric streak, the flamboyant Ghalibaf was best placed to reach out to non-conservative sections of the electorate.

The combative mayor performed exceptionally well in the three live televised debates, effectively overshadowing the clerical establishment's candidate, Seyed Ebrahim Raisi. By framing his campaign in terms of social justice and inclusivity, Ghalibaf successfully brought the elitist nature of the Rouhani administration into sharp relief.

Ghalibaf's departure was arguably the principlists' biggest tactical error as a significant share of his votes probably went to Rouhani. Conversely, had Raisi pulled out of the race, most if not all of his votes would have been absorbed by Ghalibaf and, to a far lesser extent, the minor conservative candidate, Mostafa Miraslim.

Although this would not have been enough to defeat Rouhani, it would have at least significantly reduced his majority and could have dragged the race to a second-round run-off. The repercussions may well have been profound as a more modest mandate would have significantly curtailed Rouhani's ambitions as well as his freedom of action in his second term.

Raisi proved to be a singularly uninspiring candidate who was manifestly unable to reach out beyond the principlists' traditional and conservative bastions. This forced him to make unusual gestures, such as meeting Amir Tataloo, a music star famous for mixing Persian rap, pop and R&B styles.

On the face of it, Tataloo is as far removed from the principlist mould as is possible, and the meeting (and Tataloo's endorsement of Raisi) was widely interpreted as a desperate bid to reach out to culturally progressive, if not subversive, segments of the youth vote.

At a deeper level, Raisi's central campaign theme, namely social justice, failed to win traction owing to the gap between the candidate and his message. As custodian of the Astan Quds Razavi, Raisi presides over a vast business and charitable empire (with an estimated annual revenue of $15bn) that is notorious for lack of transparency and tax avoidance.

Whither the principlists?

It is difficult to over-estimate the scale of the principlists' defeat. Rouhani was a vulnerable candidate who was fully exposed on the economic front owing to his administration's failure to turn around the economy. More broadly, the incumbent has serious leadership and personality flaws which the principlists and conservatives failed to exploit.

There are two ways to explain this defeat and its repercussions. The first, and more optimistic, assessment is that Iranian politics has stabilised around cyclical transfers of power between the reformists and the principlists. Based on this assessment, a sitting president from either tendency can expect to serve two full terms (totalling eight years) before the competing current regains power.

It is worth noting that this strategic assessment of the state of Iranian politics is only valid if we consider the Ahmadinejad (2005-2013) and Rafsanjani (1989-1997) administrations as either principlist (in the case of the former) or quasi-conservative (in the case of the latter). In reality, neither administration was either principlist or conservative in the strictest meaning of the terms.

The second, and more realistic, assessment is that the principlists are set for a prolonged period of opposition, at least in so far as the executive branch of government is concerned. The scale of Rouhani's victory clearly indicates that core principlist values do not resonate with a majority of the Iranian people.

To be fair, the principlists appear to be taking the defeat in their stride. In a lucid post-election analysis, leading principlist ideologue Abdollah Ganji attributes Rouhani's victory to his ruthless will to power. Moreover, Ganji appears to conclude that Rouhani has shifted to the reformist camp by embracing the principles of liberal democracy.

This conclusion is important in so far as it hints at an aggressive oppositional policy by principlists. The principlists may well be looking at recreating the polarisation of the heady reformist years of the early 1990s and early 2000s when the Mohammad Khatami administration was paralysed by successive crises.

This strategy is all the more credible in view of the principlist ethos of the non-elected power centres in Iran, principally establishment stalwarts such as the judiciary, the Council of Guardians and the Assembly of Experts, in addition to the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC).

By closely aligning with these power centres (as they did in the reformist years), principlist and conservative factions can mount an effective challenge aimed at frustrating Rouhani's policies and ambitions.

However, if the principlists are serious about a come-back they would need to focus less on adversarial policies and instead look inward by reframing their principles and the manner in which they interact with the Iranian electorate.

Whilst principlists by definition cannot surrender their ideological narrative (centred on the foundational principles of the Iranian revolution), they can move more toward the centre ground by softening their rhetoric and embracing the aspirations of the urban middle classes.

The urban middle class is the reformist-centrist coalition's core constituency and to make any headway in electoral terms, the principlists need to refrain from continually alienating this powerful group.

Rouhani: All-powerful?

As the election campaign was centred on economic issues, Rouhani's first priority in his second term is to turn around the economy with a view to combatting structural defects, notably chronic long-term unemployment and pervasive tax avoidance.

Already Rouhani's opponents are casting doubt on his ability to follow through with his promises by critiquing the government's post-election economic priorities plan. The IRGC-connected Fars news agency argues that this plan, which is centred on 14 economic-related priorities, is similar to one published four years ago, and hence never properly implemented.

Beyond the economy, Rouhani has dangerously raised expectations in the political sphere through his calculated polarisation centred on framing his principlist opponents as "extremists". By signalling a shift toward the reformist camp, Rouhani is effectively embracing their political demands, which centre on greater freedoms and the opening up of the political system. In immediate terms, the reformists seek the release from house arrest of Green movement leaders Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi.

Almost inevitably, Rouhani is going to disappoint his energised constituency as he doesn't have the power to satisfy reformist demands

Almost inevitably, Rouhani is going to disappoint his energised constituency as he doesn't have the power to satisfy reformist demands. If, for example, Rouhani lobbies for the release of Green movement leaders, he will run into a wall of opposition from the conservative establishment, as well as the leader, Ayatollah Khamenei.

Rouhani's relationship with the leader will be one of the defining features of his second term. Historically, owing to the structural tensions of the Iranian political system, second-term presidents clash with the leader. In Rouhani's case the clash may well be acute (with unforeseen consequences), particularly if the president proves determined to press home his advantage.

Foreign policy

As the landmark nuclear deal (known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action or JCPOA) of July 2015 was Rouhani's biggest achievement in his first term, he will be determined to safeguard the deal at all costs. This may prove tricky should the Trump administration begin calling for revisions or amendments to the deal.

Equally, in the event of the United States attempting to broaden the scope of the JCPOA, by for example targeting the Iranian ballistic missiles programme, Rouhani's detractors in the IRGC will dig deep with a view to resisting US demands. The ensuing political and diplomatic spats will inevitably hurt Rouhani.

Foreign policy was not a big feature in the election campaign, and as a consequence Rouhani is not under huge pressure to make diplomatic breakthroughs in Iran's regional and international relations.

In so far as regional proxy wars are concerned, the Iranian government does not have the final say on how these complex policies are formulated and implemented. It is the IRGC, and specifically the expeditionary Qods Force, which has primacy in this arena. This is unlikely to change in the next four years.

At a more strategic level, Rouhani supporters in Iranian diplomatic circles see his victory as a quest for normalisation and rationalisation at the domestic level and by extension in Iran's foreign policy.

But crucially they see this as a gradual process and as part of a wider and long-term shift in Iranian politics whereby the central principlist/reformist split develops into a more complex polity underpinned by fully functional political parties.

In short, don't expect Rouhani to perform miracles.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.