The dramatic rise of the Islamic State in Tunisia

TUNIS: On 18 May, a little known Tunisian militant organisation calling itself Mujahedeen Tunisia Kairouan took to Twitter to declare its allegiance to the Islamic State group. It took IS three days to acknowledge the message. Few others paid much attention.

One month, eight days and 39 lives later, that situation appears unimaginable. Last week’s deadly attack on tourists at a beach resort in Sousse by a Mujahedeen Tunisia Kairouan-linked gunman appeared to confirm the group’s ascendancy, and the ability of IS to outmanoeuvre al-Qaeda in wielding local influence.

The appeal of IS among some sections of Tunisian society, especially in the country’s economically deprived hinterland where anger and disaffection is most widespread, was already well entrenched.

Tunisia has contributed about 3,000 fighters to the war in Syria and Iraq. Less well known is the fact that the Tunisian interior ministry says it has prevented a further 12,490 people from joining the conflict. While that figure has been disputed, it offers a yardstick of the groundswell of resentment that the Tunisian state is facing.

Tunisia is no stranger to these issues, with Tunisians long drawn to jihadist causes in Afghanistan, Chechnya and Algeria. But for those leaving for the battlefields of Iraq and Syria in recent years, IS has become the main destination, according to Mohamed Iqbel Ben Rejeb, the president of the Rescue Association for Tunisians Trapped Abroad, a voluntary organisation working with the families of some of those who have gone to fight.

“In the past, they all left to join (the al-Qaeda-sponsored) Jabhat al-Nusra. However, since around July 2013, everybody leaves to join Daesh [IS]. Nobody is interested in anything else,” Rejeb told Middle East Eye.

Domestically too, Tunisia has been a target of attacks in the past. From the bombings of hotels in Sousse and Monastir in 1987 through to last Friday’s massacre, violent extremism has played a periodic role in the country’s public life.

But it was only in 2012 with the establishment of Uqba Ibn Naffi Kaliba (Katibat Uqba), an al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb-sponsored group based along the mountainous border with Algeria, that the threat against the country assumed a more tangible form.

A low-level insurgency has raged along the border ever since. Yet, in recent months security forces appeared to have turned the tide, with much of Katibat Uqba’s leadership killed and its remaining forces isolated in the mountains.

For Tarek Kahlaoui, a former director of the Tunisian Institute of Strategic Studies, the mystery, given Katibat Uqba’s relative weakness and the appeal of Syria as a destination for young Tunisians, is why it took IS so long to assert itself.

“You have to remember that al-Qaeda had all the advantages that come with being the first here. Through their public presence, Ansar al Sharia, they were able to establish pretty formidable networks. Ansar al Sharia might have been formally disbanded [the group was declared a terrorist organisation in August 2013] but their networks remained, ensuring that loyalty within the field remained with al-Qaeda,” Kahlaoui told Middle East Eye.

Aliance against the state

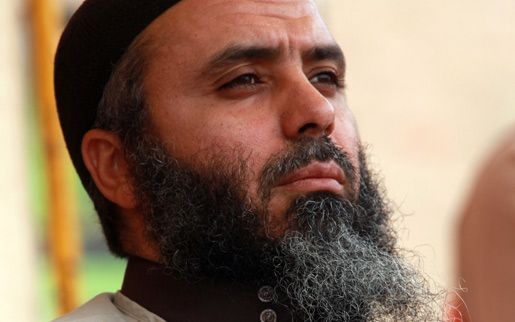

But Kahlaoui said the diminishing influence of Abu Iyadh-Seif Allah Ben Hassine, Ansar al Sharia’s founder, who on Friday the New York Times reported had been killed in June by a US airstrike in Libya, had led to a power vacuum that other factions had sought to fill.

IS declared its aspirations in Tunisia at the end of 2014 when two Tunisians pictured in front of the self-declared caliphate’s flag urged their compatriots to wage jihad in their homeland and to swear allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, IS’s leader.

In another video in April, IS called on its “brothers in Tunisia” to travel to Libya, as those responsible for the attacks in Sousse last week and at the Bardo museum in Tunis in March had done, to train for future operations within Tunisia.

Ludovico Carlino, Middle East North Africa analyst at IHS Country Risk, said the situation in Tunisia appeared to mirror the wider trend of IS’s influence increasing as al-Qaeda’s has diminished.

“It is also a matter of support. Al-Qaeda is probably not able to guarantee the same level of support as Islamic State, in this case from Libya. This clearly translates for al-Qaeda into fading relevance,” Carlino told Middle East Eye.

But with responsibility for the Bardo museum attack still disputed by the Tunisian security services, who blamed Uqba Kalibat, and IS, which claimed it for its own, there exists for Kahlaoui the possibility of a third, more ominous, possibility.

He points to the fact that the gunmen responsible for both the Sousse and Bardo museum attacks appeared to have trained together at the same time in Libya.

“That raises two possibilities. Either we’ve been entirely wrong about who organised the attack at Bardo. Or, if we consider the disputed claims and the fact that some IS-aligned media platforms have been calling for some form of co-ordinated action within Tunisia, we’re left with the real possibility that these two groups may be aligning within Tunisia against the state.”

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.