Lebanese businesses squeezed as US sanctions hit Hezbollah

Last November, Fadi Serhan, the owner of Vatech, an electronics shop in Beirut, discovered he was being named by the US Treasury as having purchased on behalf of Hezbollah “sensitive technology and equipment” such as “unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and accessories, and various electronic equipment”.

He was placed on a list of "procurement agents for Hezbollah" that bar Americans from doing business with him. Within days, all of his bank accounts were closed.

Then in December, Serhan was on holiday in the Gulf when his friends called him to break the news that he had also been added to a list of 99 entities or companies targeted by the “Hizballah International Financing Prevention Act (HIFPA)”.

The US lists Hezbollah as a terrorist group and accuses it of involvement in numerous anti-US attacks, including the bombings of the US embassy and a Marine barracks in Beirut in 1983 and the hijacking of an American airliner in 1985.

The bill signed by US President Barack Obama in December 2015 went into effect in April this year and aims to prohibit US individuals and companies from doing business with those named.

Serhan says the news came as a shock.

“I'm not involved in any way with Hezbollah,” he told Middle East Eye. According to Serhan, Banque du Liban, the Lebanese central bank, told him “they don’t have anything against me, but ‘the issue needed to be solved’”.

Efforts to contact US authorities went unanswered. His shop, which he established 20 years ago, is going out of business, and he plans to close it by the end of the year.

Banque du Liban promptly closed down all the accounts on the list and regulated the closure of further ones suspected of being affiliated with those targeted by the American sanctions.

“It is obvious that more than 99 accounts were closed, otherwise there wouldn’t be such a hassle concerning the practices of the banking sector,” a Banque du Liban employee, speaking on condition of anonymity, told MEE without giving a precise estimate.

“The account of a colleague of mine, who is the daughter of an ex-member of parliament affiliated to Hezbollah, was closed. The mere fact that this happened shows an exaggerated trend in the banking sector,” he added.

Hezbollah is part of the government in Lebanon and has participated in national elections since 1992.

When asked about how individuals were being chosen beyond those designated by the US government, four of Lebanon’s biggest banks, Bank Audi, Blom Bank, Credit Libanais, and Byblos Bank declined to comment.

But at stake lies their access to dollars, and more broadly to the international financial system.

Lebanese banks cannot afford not to enforce American regulations in an economy that has been heavily reliant on the dollar to maintain economic stability since the 1975-1990 civil war.

Bassem El Chab, a member of parliament who was commissioned as part of a delegation visiting the US to speak with representatives concerning the repercussions of recent American financial measures on Lebanese businesses, was more forthcoming with his analysis of these events.

“Lebanese banks have been very compliant - overly compliant. Fact is, should any of these banks not be compliant they'd be cut off from the international banking system,” Chab said.

'Pro-American, anti-resistance'

It was rumoured in the Lebanese media that certain banks had become overly zealous in applying American sanctions out of fear of being blacklisted themselves.

“The whole banking sector was criticised [by Hezbollah] for being pro-American, anti-resistance, but ordinary people are weary of this mindset. If the banking sector collapses, everyone will suffer,” Chab said.

American officials have taken great pains to make clear that legislation is not specifically aimed at the Shia population.

A US Treasury spokesperson said: “The safety, soundness, and security of the Lebanese financial system is a priority for the United States.”

During a visit in May this year to the US embassy in Beirut, Daniel Glaser, the assistant secretary of the Treasury for terrorist financing, added that “the law does not target Lebanon, nor does it target the Shia community. HIFPA targets Hezbollah’s financial activities worldwide, and [the law] will be implemented worldwide”.

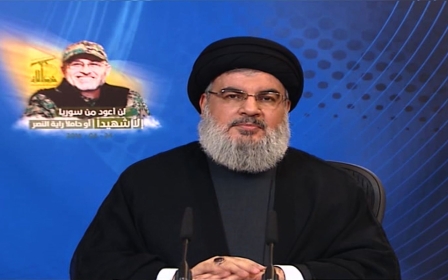

At first, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah responded with speeches criticising the banking system for complying with the American measures and suggesting that Hezbollah supporters could withdraw their money from local banks.

A bomb blast outside the headquarters of Blom Bank in Beirut on 12 June was interpreted as a retaliatory move by Hezbollah, prompting worry that the dialogue between financial officials and the Lebanese political party was broken.

However, after the explosion Hezbollah toned down its criticism of the banking sector. When asked to comment on the current implementation of the US law, Hezbollah’s media office said: “Hezbollah is currently negotiating with the central bank and commercial banks as a group. When they are done, Hassan Nasrallah will address the issue of negotiations and their outcome in a speech.”

On Friday, Lebanon's Daily Star newspaper reported that Hezbollah was seeking a truce with the central bank and had reached out to the governor of the bank, Riad Salameh, to thank him for the way in which the bank had handled the US sanctions issue.

Even if it seems like Hezbollah has entered negotiations, many worry that implementation of the law will only further destabilise Lebanon’s economy, which has been hit hard by the war in Syria.

“If you take a look at Lebanon’s economy today, the only sector that’s still kicking is the banking sector. Tourism is dead. Real estate is paralysed. Agriculture and industry have no access to international markets because of the war in Syria,” said another Lebanese MP, who was part of the delegation to Washington but asked to remain unidentified.

According to Ali Hamdan, an adviser to Nabih Berry (chairman of the Shia Amal movement and speaker of parliament), many issues are at stake.

“There are some important hospitals in Lebanon that are linked to Hezbollah. They used to deal directly with the government for all financial matters. Now, the Central Bank has to act as an intermediary,” he said.

The main Hezbollah-affiliated hospital, Arrassoul al-Aazam, located in the southern suburbs of Beirut, declined to confirm whether they had financial problems.

The nearby Bahman medical centre, which is affiliated with the al-Mabarrat foundation established by late Shia cleric Sayyed Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah, was quick to clarify that it had not experienced financial problems.

“I can assure you that our accounts are running fine,” said its director, Ali Krayem.

While the al-Mabarrat foundation is not on the OFAC list, in May it told the Reuters news agency that some of its accounts had been frozen by Lebanese banks.

“The problem is the same for Hezbollah municipalities,” said Ali Hamdan. “Will people be sanctioned for paying their taxes?” he said, before adding that the central bank had managed to find a solution for that problem, but had yet to present it publically.

Cash only

What mostly worries Hamdan is the development of a parallel economy.

“It will not benefit anyone to encourage the development of a cash economy in Lebanon. Nobody wants to support terrorism and Lebanon suffers from it. But [the way the Americans are going about it] is comparable to me trying to shoo a fly off your face by hitting you with a heavy ashtray.”

Fadi Serhan’s shop has operated only in cash since November.

Lebanese economist and former finance minister Georges Corm is less alarmist.

“This law cannot impact the banking sector. The Lebanese diaspora will continue to transfer money into the country,” he said.

Lebanon’s economy is heavily reliant on remittances sent from almost 14 million citizens around the world. However, the level of remittances have been decreasing: according to the World Bank, in 2015 the amount totalled $7.2bn, down from $7.4bn in 2014.

While the fall has been mostly attributed to a sluggish world economy, some fear that the sanctions will exacerbate the issue.

“Remittances are already affected by the American sanctions. It’s getting increasingly complicated to send money in and out of Lebanon now,” said Hamdan.

For Corm however, the real issue at hand is that the law will not meet its end goal, which is to weaken and isolate Hezbollah.

“It’s not by sanctioning Hezbollah financially that they will disappear. They are cooperating with the Lebanese army on preserving the safety of the country,” he said.

Instead, to weaken Hezbollah without damaging the economy, he suggested focusing on maintaining stability within the country.

Hezbollah’s popularity spiked during its 2006 war with Israel, despite the widespread damage caused by the conflict, and Corm said a lack of security remained key to the group’s enduring influence.

“As long as the environment of Lebanon remains so dangerous, support for Hezbollah among large parts of the Lebanese population, both Christian and Muslim, will remain.”

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.