Jordan activists targeted after MP says gay people unwelcome

LGBT activists in Jordan have been targeted with hate speech and threats after a Muslim Brotherhood MP said homosexuality was unwelcome in the country.

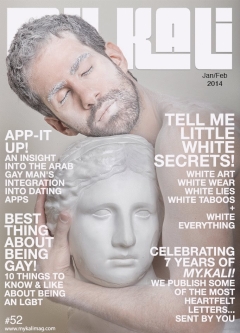

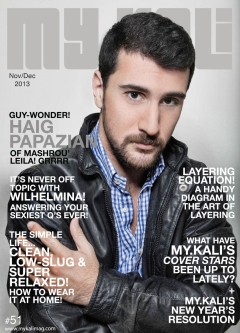

Jordanians took to social media last month as a Twitter feud escalated between My Kali, a local LGBT online magazine and MP Dima Tahboub, who is the English-media spokeswoman for the Islamic Action Front, the political arm of the Muslim Brotherhood in the country.

Last week, Tahboub said My Kali had been shut down when she approached Jordan's Media Commission regarding the magazine's registration status.

In an open letter to Tahboub on Medium, My Kali said it had been blocked for over a year and questioned her motives in claiming credit.

"From where we stand it seems she's trying to pose as the hero, the MP who shut down a pro-LGBT platform in Jordan," My Kali founder and creative director Khalid Abdel-Hadi told Middle East Eye.

My Kali began life as a series of diaries documenting Abdel-Hadi's experiences and grew into a grassroots platform for the LGBT community before becoming an online magazine in 2008.

Tahboub said her actions were "in harmony with the general culture of Jordan," adding: "I had a lot of people sending messages and emails welcoming what I did."

Legal, but still targeted

Jordan was the first monarchy in the region to decriminalise homosexuality when it adopted its own penal code in 1951. Prior to this, same-sex activity was illegal under the British Mandate Criminal Code Ordinance.

In most Middle East countries, homosexuality remains criminalised and punishable by prison sentences or even death. Where is it not, in countries including Egypt, Iraq and Jordan, LGBT people may still be targeted under other laws.

According to Adam Coogle, Middle East researcher at Human Rights Watch, "A lot of countries in the region attempt to scapegoat LGBT people," but historically in Jordan, he said, "authorities choose not to use LGBT issues to appease public opinion.

"This affair is an exception," he told MEE.

However, the issue of LGBT rights in a conservative society remains deeply divisive.

In June, Jordanian authorities cancelled a concert by Lebanese band Mashrou' Leila for the second year in a row, prompting a wave of pro- and anti-LGBT sentiment surrounding the band, whose lead singer Hamed Sinno is gay.

Tahboub was one of several Jordanian MPs who called for the cancellation and told CNN that the lead singer's sexuality was "exactly" the reason behind the move, describing the band's lyrics about sexuality as "against the religion and norms of the country".

Her views then hit headlines again after an interview on DW Conflict Zone with British journalist Tim Sebastian, when Tahboub confirmed her message that homosexuals are not welcome in Jordan.

She later tweeted a picture of a gay couple getting married, commenting: "This is what Tim Sebastian taunted me about in his program!!! What do you know?!?! Shall I say congratulations?!?"

LGBT activist Hasan, who prefers not to give his full name, was among those who responded, tweeting screen shots of Tahboub's posts under the caption: "A parliament member spreading hate speech against the LGBT community in Jordan."

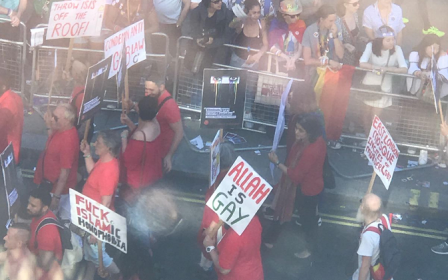

"There are a lot of crises to address in Jordan and instead she focuses on posting tweets targeting the most vulnerable community in the country," said Hasan, who had recently floated on his feed the idea of hosting the first gay pride event in Amman.

'Bats of the night'

Tahboub responded with a tweet in Arabic saying: "Those bats of the night who have no place, and their identities are hidden, challenge the people and the law by publicly marching and condoning homosexuality in Amman."

"After that a lot of her followers started sending me threats," Hasan said.

Tahboub elaborated in a discussion with Roya, telling the local news outlet: "We regard gays from a moral and religious perspective, that they are a community who is completely rejected, alien to our religion and tradition and the Jordanian people's cultural norms."

I don't see them as criminals, I see them as people with mental disorders who need to be treated using psychology

- Dima Tahboub, Muslim Brotherhood MP

She continued: "I don’t see them as criminals, I see them as people with mental disorders who need to be treated using psychology."

In the country's capital, Amman, there are a few discreetly LGBT-friendly cafes, but despite small pockets of acceptance, Jordanian society remains largely resistant to sexual freedoms that fall outside perceived norms.

"Jordan is like any other country in the MENA region with judgemental citizens who won't fail to let you know if they think you’re different," Abdel-Hadi said.

In a 2016 report on digital security, Abdel-Hadi, who also runs digital security workshops, writes that local media is partly to blame.

"The constant association of LGBT people with drugs, sex scandals, and prostitution reinforces a public image of LGBT people as uniformly deviant."

An 'other' within Jordanian society

But many outlets choose to ignore the LGBT community in Jordan altogether.

"Journalists only cover LGBT issues in the context of Western LGBT rights movements, reinforcing opponents' views that LGBT people are a distinct 'other' in Jordanian society," the report said.

It cites an incident in May 2015, when then US ambassador to Jordan Alice Wells attended an International Day Against Homophobia and Transphobia event hosted by activists in Amman.

Many local media, forced to acknowledge the event by Wells' presence, ran derogatory headlines, such as "Meeting for Homosexuals and Perverts in Jordan Sponsored by the US Ambassador".

The widespread negative coverage preceded a noticeable uptick in physical and verbal attacks against LGBT people, the report said, with several videos surfacing on social media, including one showing an assault against a man in a conservative area of the capital.

According to activists, incidences of bullying, blackmail and violence against LGBT people are common, but rarely reported, with many fearing the consequences of being outed.

Talking to MEE, a My Kali contributor who goes by the pen name AW Rahman, said: "It's one thing if you come from an affluent, educated family in Amman, but if you live in a small village you can't afford to be visible."

Legal grey area

The online environment is little safer.

The report references an incident in 2014, when an unidentified source published a post exposing the profile pictures of Jordanians using LGBT dating apps Grindr and Scruff, sparking panic in the community. It also describes other instances of people approached through the apps and blackmailed or attacked.

According to Rahman, the law offers little protection. "Homosexuality is not illegal but it's not exactly legal either," she told MEE, explaining that LGBT people are noticeably absent from the list of minority groups eligible for protection under Jordanian law.

Nor has the country signed any international treaties safeguarding LGBT rights.

How can you give a group of people rights if they don’t exist?

- AW Rahman, My Kali contributor

Many deny the presence of LGBT people in Jordan entirely, Rahman said, "and how can you give a group of people rights if they don’t exist?"

As a minority within a minority, transgender people are particularly vulnerable, activists say.

"Society here doesn't differentiate between being lesbian, gay, transgender, bisexual and intersex. There is a lack of education and awareness about what LGBT means," said political activist Sanad Nawar.

This is the void My Kali has sought to fill since it launched over 10 years ago.

"We are trying to bridge the gap between LGBT and non-LGBT society and reach out to people who want to learn more about this community. We do not speak for one group only. My Kali covers freedom of speech, feminism, art, music and culture," Abdel-Hadi told MEE.

However, people often misinterpret the publication's position. "They go to the website thinking they'll see pornographic pictures but what they find are interesting images, intellectual articles and different perspectives."

Growing up in Amman, Abdel-Hadi said, there was no outlet for LGBT expression.

"Local media doesn't speak about this subject, so you don't really have that sense of ownership – of claiming an LGBT identity."

My Kali has been instrumental in carving out a space for the community online, "providing a Jordanian reference to being LGBT so you don't have to look to the West," he said.

"It's also a medium for a lot of people in Jordan and the MENA region who cannot express themselves freely or use social media to put their words out there."

Messages of support

The impact of this has been evident in the messages of support flooding in.

Prominent Egyptian-American journalist Mona Eltahawy tweeted her "Love and solidarity with the magazine & LGBT community," while LGBT group All Out posted on its Facebook page: "My Kali is an important voice for love and equality in the Middle East ... This incitement to hatred is dangerous for the whole LGBT community in Jordan and it is despicable."

Many My Kali supporters in the region have shared the publication's open letter, which calls for "A Jordan that is safe for all - a country governed by the rule of law, justice, and pluralism".

It laments the state of freedom of speech in Jordan, citing its fall to number 138 on the 2017 World Press Freedom Index. Tahboub said: "Democracy gave you the seat to fight for the things you and your constituents believe in. We only ask that you give all Jordanians the space to exercise our opinions in the same way."

Despite a decision to delay My Kali's planned re-launch till next month while sensitivities subside, the team said it welcomes the visibility Tahboub's comments have generated.

"Ten years ago, Jordan did not have this kind of dialogue or discussion regarding LGBT issues. Now you're talking about a member of parliament who represents the Brotherhood actually trying to take action against our platform," said Abdel-Hadi.

"That on its own is an acknowledgement."

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.