Old memories haunt Turkey’s Armenians as nationalist feelings rise

ISTANBUL, Turkey – Painful collective memories continue to haunt Turkey’s Armenian community, and its members face a renewed period of apprehension as the country’s leaders and politicians adopt an increasingly nationalist tone.

The latest surge in nationalism is mostly linked to the renewed war against Kurdish militants in southeast Turkey. Yet attempts to pin even the Kurdish conflict on Armenians are never far off.

The tendency of sections of the media to blame all the country’s ills on Armenians has many of the 50,000 to 70,000-strong Turkish-Armenian community, never fully at ease, on edge.

“I stopped wearing my necklace that has an ornamental cross on it a few months back. Not because I wanted to but due to fear,” said Jaklin Solakyan.

“I am really fed up of being denigrated and discriminated against. This is my country, and I am an equal citizen. Why do we need to be constantly targeted because we are minorities?” Solakyan, 40, told Middle East Eye.

“Just look at the media. Often you will find articles claiming a bible was found in PKK [Kurdistan Workers’ Party] camps or that the actual fighters are Armenian and such,” she said.

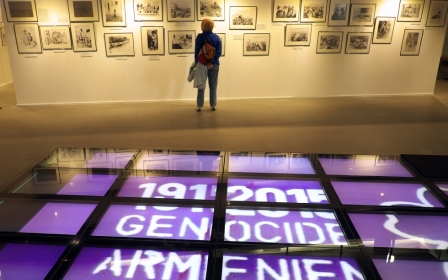

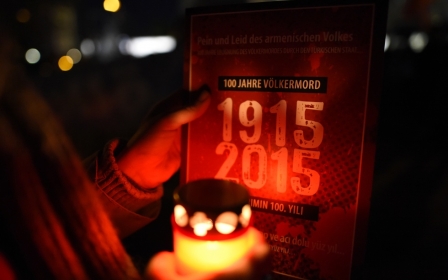

It is a hostility that can only heighten this weekend as Armenians mark 101 years since the deaths of millions of people at the hands of the Turkish empire during World War One. Armenia calls it a genocide. Turkey does not.

Yetvart Danzikyan, the editor-in-chief at the weekly Armenian newspaper Agos, said his community in particular and all minorities in general, become alarmed when nationalistic rhetoric flares up.

“The Turkish state always says Armenians are behind Turkey’s Kurdish issue. It was the same during the fierce clashes of the 1990s as well," Danzikyan said.

"The state wants to make it into a religious issue, and such rhetoric is an attempt to influence and rally to their side pious Muslim Kurds, who make up the majority of Turkey’s Kurds."

In Danzikyan’s view, the media has always been used by the state to further claims that it is mostly Armenians who make up the PKK’s fighters and such.

“The state becomes complicit by keeping silent in the face of such allegations,” he said.

Turkey’s religious minorities have been left with deep scars due to a host of events in the 20th century, including the wealth tax of 1942 on non-Muslim Turkish citizens, and the Istanbul pogrom of 1955 on Greek and Armenian minorities.

Illegal Armenians most at risk

Regardless of the hostility endured by the Armenian community here, it is believed that there are roughly 100,000 Armenian nationals living illegally in Turkey, most of whom are in Istanbul.

Their situation remains precarious despite the goodwill shown by officials. Economic despair pushed many of them to travel to Istanbul despite the fear instilled in them via their own education system.

Visas to Turkey are easier and cheaper to obtain compared with visas for western European countries, and Turkish authorities turn a blind eye when such Armenians overstay and seek employment in the informal economy.

Anna, 35, came to Istanbul in 2011 on a tourist visa with her husband and two young children.

Ever since, she has been living and working illegally. The lack of diplomatic relations between Ankara and Yerevan also means she and her family have no access to consular services in Turkey.

“We had no choice. There was no way we could earn a living at home. We put all our fears aside and came after a cousin told me the people were different and not bad to us,” she said.

“In any case it is better than Europe where they won’t even let us in.”

Anna said that despite the hardships they have had to endure they have never been treated badly, but that in the last few months many friends have told them to consider returning home.

“Our friends say the worsening security situation means we would be among the first to face the backlash. Now we are scared, and this might be our last year here. I don’t want my children to grow up surrounded by hostility.”

Ani Hovhannisyan, 27, who was a teacher back home, came to Istanbul seven months ago with her husband. They are both legally employed. The language barrier means they are spared from understanding the jibes their Turkish-speaking brethren face. Yet Hovhannisyan yearns to return home.

“It is a beautiful city, and the people are very nice. But I would still love to return home soon. I am not happy here,” said Hovhannisyan.

“Even though I know that the people and the government are separate things, we have a collective memory of our national pain, and the Turkish government’s policy of denying the cause of our pain hurts very badly."

General view of Armenians more hurtful

But even more than politically motivated nationalistic remarks it is the remarks of many ordinary citizens that many Armenians find most painful.

“Do you know how hurtful and rude it is when people call you an infidel?” said Avedis Kendir.

Kendir, 57, a world-renowned jewellery designer who even counts Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II among his clients, said this prejudice is so entrenched that people end up insulting Armenians and other religious minorities even while attempting to compliment them.

“I feel pained when people who decide they like me say ‘I wish you were not Armenian’. In their minds that is supposed to be a compliment stating how much they like you as a person,” Kendir told MEE.

Such behaviour and attitudes are sometimes put down to sheer ignorance, but Solakyan believes a large part of it is due to how Armenians are depicted in the education system, and that many of those who behave this way are educated people.

“I went to an Armenian school, and even there the textbooks, which contain a state-imposed curriculum, paint Armenians in the worst possible light. You cannot put it all down to ignorance,” she said.

“Imagine what we feel when even the president of our country uses the word Armenian as if it is a derogatory word.”

Tense times

Even at the best of times, the period around 24 April is one of high tensions between Turkey and Armenia as both countries lobby the international community to have their view heard about whether the tragic events of 1915 constitute genocide or not.

The Republic of Turkey strongly rejects the use of the term genocide to describe the events of 1915 during the final years of the Ottoman Empire.

It has repeatedly called for the archives of both Turkey and Armenia to be opened up to neutral scholars for study.

The current nationalism-tinged statements from officials are in sharp contrast to the not-so-distant past when the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) represented the strongest hope for an inclusive and reformist Turkey where all its people would be embraced.

In 2014 Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who was prime minister then, became the first Turkish leader to express regret and referred to the 1915 mass deaths as “our shared pain".

The present Turkish prime minister, Ahmet Davutoglu, foreign minister at the time, even wrote an article for the Guardian newspaper citing Erdogan’s remarks and calling for reconciliation.

Danzikyan is sceptical of the intent behind such statements but said the AKP is very unpredictable and it would not come as a surprise if a stronger reconciliatory message were to emerge even amidst this surge of nationalist sentiment.

“There are many who will tell you that those remarks of shared pain from 2014 are just another form of denial. There is still no attempt to research and explain the why and how of the deaths of so many people,” he said.

The AKP displays “astonishing levels of elasticity,” and it would not be a surprise if “an inclusive message” came out on 24 April again, according to Danzikyan.

For Kendir, these cyclical waves of nationalist-inspired hate that inevitably end up targeting the Armenian and other minority communities in Turkey is simply an act of political exploitation carried out by both Turkish and foreign actors.

“This shameful problem for my country existed when I was born, and I doubt it will be resolved during my lifetime either,” he said.

“It is really sad, and I hope it is sorted out one day because as far as cultural similarities are concerned you won’t find anyone closer than Turks and Armenians.”

Note: Anna’s real name has been omitted

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.