Air strikes and guerrilla fighting: The tactics deployed by Sudan's warring sides

Adam Osman remembers it all too well. Now living in Abu Shoak, a camp in North Darfur for internally displaced people, Osman told Middle East Eye about the day his town was taken by forces allied to the Sudanese state.

It was 2004 and Kutum, the town in North Darfur, was subjected to aerial bombardment targeting the Sudan Liberation Movement, which was fighting the government of then-president Omar al-Bashir, for a week. Bashir’s forces believed that the village was supporting the insurgency against him.

After the air strikes came the ground attack. Janjaweed militias, which had been empowered by Bashir to brutally crush rebellions in the remote west of Sudan, attacked Kutum, killing civilians and burning buildings.

“They were allied together,” Osman said, of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Janjaweed Border Guards militia headed by Musa Hilal. “They were responsible for the on-the-ground cleansing of the rebels and civilians.”

Today, the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which grew out of the Janjaweed militias, is at war with its former ally, the Sudanese army. Its commander, General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known as Hemeti, was once a Janjaweed leader in Darfur.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“Hemeti is fighting for himself right now,” Osman said. “He says he is fighting for the Sudanese people, but he is not.”

But like many other people in Darfur, Osman can see the tactics that were used to devastate his land being used once more, and by both sides of the conflict that has torn Sudan apart since it began on the morning of 15 April.

Cycles of war

For decades, civil war in Sudan took place away from the country’s capital, Khartoum. In the South Sudanese civil war, the war in Darfur and the conflict in South Kordofan and Blue Nile states, a particular set of military tactics were deployed.

The Sudanese Armed Forces and other state-sponsored actors would dominate the air, raining down air strikes on rebels and insurgents looking to control the ground by utilising guerrilla tactics.

Now, the streets of Khartoum and its twin city, Omdurman, which house over five million people, are caught in this same deadly dynamic, as the army uses intensive air strikes against its ally-turned-enemy, the paramilitary RSF.

In return, Hemeti's men manoeuvre through the city’s neighbourhoods, still controlling the majority of Khartoum on the ground after they launched an offensive on major army government and army buildings on the morning of 15 April.

Both sides have anti-aircraft guns, anti-tank missiles, artillery and mortars. RSF fighters have been pictured with man-portable air defence systems (Manpads), surface-to-air missile systems, anti-material rifles and machine guns brought back from the war in Yemen, where the paramilitary fought on the side of the Saudi and Emirati-led coalition.

The RSF has released videos featuring North Korean and Chinese rocket launchers taken from the army, as well as battle tanks originally supplied by Ukraine. Aircraft, vehicles and all forms of weaponry from across the world are being used by both sides in Sudan’s current conflict.

Paramilitary vehicles and checkpoints dominate most of Khartoum’s main streets, arresting significant numbers of army soldiers and officers, as well as terrifying civilians stuck indoors. Those residents are starting to feel frustrated at the army’s inability to end the war, several eyewitnesses and activists told Middle East Eye.

On the other side, the SAF is using intensive air strikes to target different paramilitary camps, offices and checkpoints. The army is also using aerial bombardment to try and stop its enemy from bringing reinforcements from Kordofan and Darfur into Khartoum.

Army tactics

A Sudanese military expert, who spoke to MEE on condition of anonymity, said that the army’s tactics depended mainly on air strikes, isolating RSF units on the ground and stopping them from bringing in reinforcements, supplies and logistics.

“SAF intelligence, which has most of the data on RSF deployment, capabilities, sources of supply and logistics, has imposed very painful aerial bombardments against its enemy,” the source said. “I think they will continue until they destroy RSF ground capabilities.”

“However,” the source continued, “the RSF was part of the army’s intelligence war in Darfur and other warzones in Sudan and has understood the tactical lesson very well. They have started using the anti-aircraft guns they have to confront the drones, Russian Sukhoi and Mig jet fighters and helicopters of the SAF.”

The expert said that the RSF is looking to counter the army by drawing it into protracted rounds of street fighting, which is one of the paramilitary’s strengths.

“The RSF is using a lot of manoeuvring tactics in street fighting and guerrilla war, including the rotation of checkpoints to avoid aerial targeting, intensive anti-aircraft fire, deployment of snipers and hit-and-run attacks on SAF bases,” the source said.

From 2017 onwards, the RSF, which was established as part of the apparatus of the Sudanese state in 2013, began to establish military bases in Khartoum. The paramilitary acted as a praetorian guard for the autocrat Bashir, protecting him from the wrath of the people and from internal enemies, both real and imagined.

After Bashir was removed in April 2019 following a popular uprising, the RSF rapidly increased the process of establishing themselves in Sudan’s capital, surrounding Khartoum with bases.

The paramilitary has four big camps around the city, including Hatab camp in the north of Khartoum, Taiba in the south, West Omdurman camp and Suba camp in the east. These four bases place the RSF at the four main entrances of Khartoum state.

Hemeti’s men also have many offices in different Khartoum and Omdurman neighbourhoods, as well as the RSF tower inside army headquarters, which is close to Khartoum’s international airport and a slew of other official buildings.

The two sides have traded accusations over the use of human shields and of fighters hiding inside residential neighbourhoods.

The RSF has accused the army of being irresponsible with its use of random air strikes, which have led to many casualties.

Meanwhile, the army says its paramilitary enemy has deployed its forces inside residential neighbourhoods without any thought to the consequences that this would have to civilians. Eyewitnesses in Khartoum have told MEE that they have seen RSF fighters moving into residential homes in their neighbourhoods.

Neutralising air power

An army officer, who did not want to be named, told MEE that the RSF’s focus was on neutralising the army’s air force capabilities, which give it the upper hand in the war.

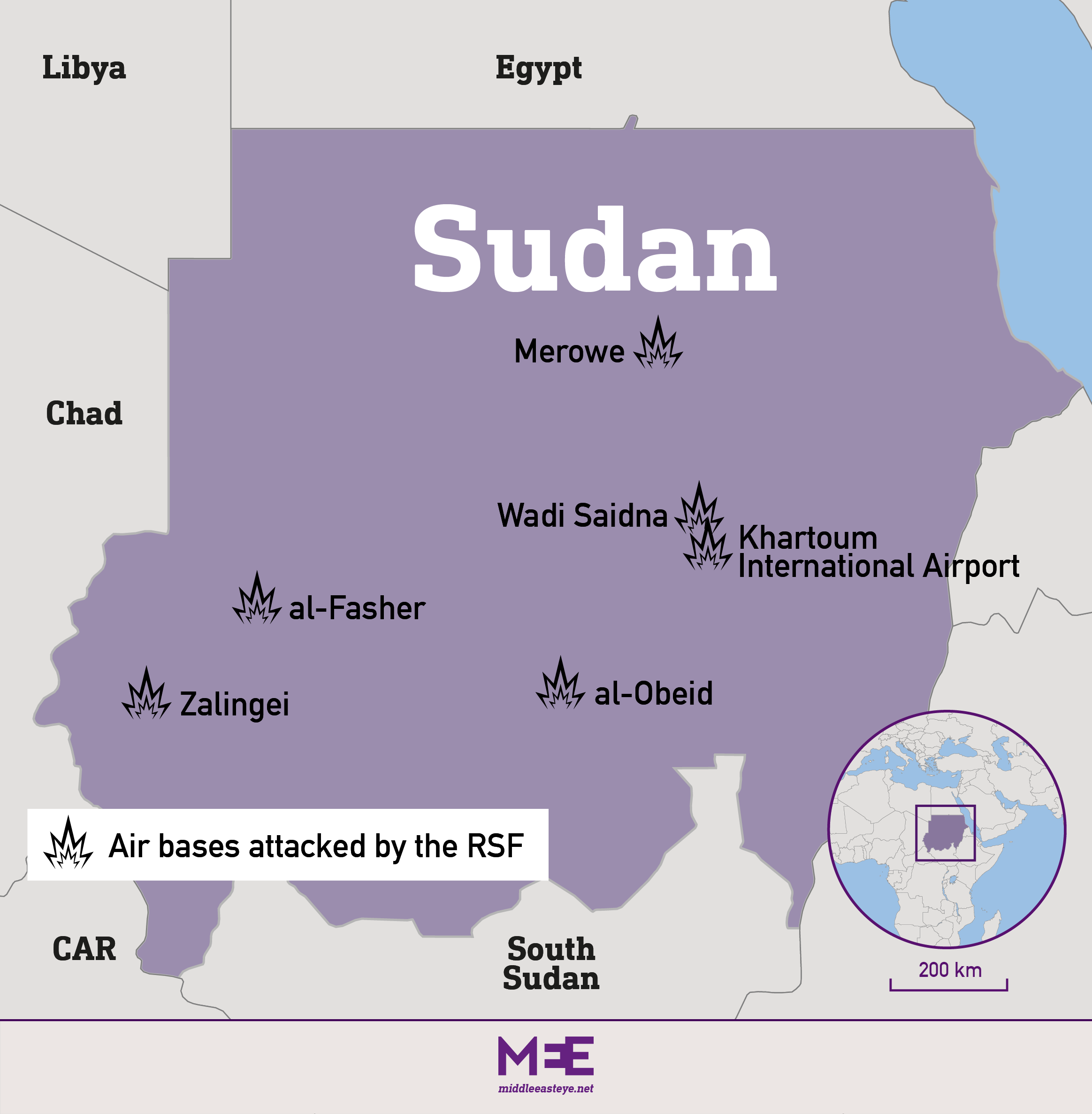

“RSF tactics depend on capturing the airports and destroying the runways in order to stop strikes. This is why we saw RSF very keen to capture the airport of Merowi before the eruption of the fighting and [it] also fought aggressively to capture the airports of Khartoum, Wadi Saidna in Omdurman, El-Obeid in North Kordofan, Al Fashir in North Darfur, Sabir airport in West Darfur and others,” he told MEE.

'The RSF has succeeded in bringing some reinforcements and supplies in from Darfur and Kordofan despite some of its vehicles being attacked'

- Sudanese military expert

“Unfortunately, the RSF has partially succeeded in this tactic: they only need to control any airport for a few hours in order to destroy it and flee,” the SAF officer said.

He further noted that his paramilitary rivals have not just destroyed runways, they have also burnt down some aircraft and planes in military airports like Jabal Awliya, south of Khartoum.

However, a source close to the RSF denied the accusations and said that the paramilitary was controlling the majority of military and civilian airports in the country and had not destroyed them intentionally.

“We have the right to stop these air forces from destroying our fighters by burning planes or blowing up runways because we have no pilots to use them and the enemy is using them against our forces and against the civilians,” the RSF source said.

“But in fact, we haven’t done that because we are controlling the majority of airports in the country.”

Supply routes

The battle to control or disrupt supply routes is another key element in the conflict, as both sides continuously look to prevent the enemy from securing supplies, logistics and military reinforcements.

A senior retired army officer told MEE that the control of supply routes was one of the most important strategic considerations in any war, adding that the position of the SAF seemed to be better than the RSF in this regard, and that the army as dominating government institutions including ministries, governors of states and more.

“In terms of supply, the SAF is in a better position as the government institutions are on its side, it has its military bases in Khartoum and other states, so it can secure the fuel, munitions, food and other needs for its forces,” the retired officer said.

“Another thing is that SAF soldiers have a way to get some rest, while that looks to be more difficult for the RSF,” the source, who could not be named, said.

“Using the air strikes, the army has destroyed many RSF convoys of reinforcements and supplies coming from Darfur and Kordofan through Omdurman. The SAF has also blocked most of the borders, especially with Libya and Chad because fighters joining the RSF could have come in from these countries,” he said.

In the first week of the war, the army captured Chevrolet, an RSF base located in the strategic triangle border region between Sudan, Libya and Egypt. Hemeti, whose family hails from Chad, has long drawn young men from the wider region into his paramilitary.

Both sides have accused the other of receiving external support. An Egyptian military source told MEE that Egyptian pilots were flying Sudanese air force planes targeting the RSF, which has said openly that its base in Red Sea state was bombed by the Egyptian air force. Egypt and the Sudanese military have denied the allegation.

The paramilitary is getting support from UAE-backed Libyan commander Khalifa Haftar.

The military expert said that the mobility of the RSF and its guerrilla tactics gave it some advantages, as it has no responsibility to protect government institutions and does not need to consider the running of the state, including the payment of salaries and other basic needs.

“The RSF has succeeded in bringing some reinforcements and supplies in from Darfur and Kordofan despite some of its vehicles being attacked,” the military expert said. “The RSF has also attacked army bases, enabling them to get weapons, munitions and supplies before they flee.”

Central Reserve Police

Just as in the Darfur war, the Sudanese Armed Forces have decided to deploy the infamous Central Reserve Police (CRP) to counter the insurgency tactics used by the RSF.

The armed police force, feared at home and abroad, was sanctioned by the United States for alleged crimes committed in Darfur, and has been accused by Sudan’s resistance committees, the organising force behind the country’s pro-democracy revolution, of committing a series of atrocities against protesters since the October 2021 coup.

The RSF has warned the armed police force not to interfere in the war, saying in a statement: “Don’t engage in a war that you have nothing to do with and do not enable the coup leaders and the associates of the old regime to use you.”

Eyewitnesses in different parts of Khartoum said that the war has aggressively entered deep into residential areas and that clashes are continuous between the central police and the RSF.

The army has also asked residents to leave their houses, with worse clashes expected in the coming days, according to Khartoum residents.

From his camp in Darfur, Osman Adam told MEE that the deployment of the CRP also echoed what had happened to him and his people. With army soldiers not seemingly equipped to handle vicious street fighting effectively, SAF air strikes are being followed up by central police fighters, who are not as afraid to die.

Two decades ago, in Darfur, Hemeti’s fighters were the men sent in by the state in the wake of intensive air strikes. Today, his men are on the other side, standing in the way of the men sent in by the army to follow the bombs that rain down from the sky.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.