Resistance and feminism: Five must-read books from Algeria

Algeria spent 132 years under French occupation, a period during which indigenous Algerians and some supportive Europeans fought a multi-pronged battle against the colonisers.

While the military aspect of the independence struggle, embodied in the struggles of fighters like Cheikh Bouamama and Zohra Drif, is what gets most attention, themes of resistance also influenced the arts, especially literature.

In return, poets, such as Moufdi Zakaria, the author of the Algerian national anthem Kassaman, helped define the revolutionary nature of the fledgling state’s cultural output.

Nevertheless, more than a century of colonisation left its mark on Algeria, and like other post-colonial countries, debates continue on the role the occupier’s language should play in the literature of a state after independence.

French is still widely used in Algerian literature, a fact complicated by the huge Algerian diaspora living in France, for whom the language has come to replace Arabic or Tamazight as the main vernacular of everyday life.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Notwithstanding, several contemporary authors, such as Amal Mostaghanemi, the late Abdelhamid Benhedouga and Tahar Wattar stand as fierce advocates of the Arabic language.

Tamazight, the language of Algeria’s Amazigh people, has yet to reach the ubiquity of either French or Arabic, but is slowly making its presence felt.

Such debates aside, the fact remains that for anglophone readers, Algerian literature remains scarce, with only a limited number of works available in English.

Here Middle East Eye recommends five books available in English that serve as an introduction to Algerian literature:

1. Inside the Battle of Algiers: Memoir of a Woman Freedom Fighter by Zohra Drif

There is perhaps no account of the eight-year-long Algerian independence struggle more famous than director Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1966 film The Battle of Algiers.

The movie is an adaptation of Yacef Saadi’s 1962 memoir Souvenirs de la Bataille d’Alger (Memories from the Battle of Algiers).

Borrowing from the title of those two prior works, is resistance fighter Zohra Drif’s more recent memoir, which was translated into English by Andrew G Farrand.

With the passing of her comrade Samia Lakhdari in 2012, alongside whom she fought the French colonialists, Drif came to the realisation that not only was she losing a dear friend, one she considered a sister, but also an important figure in Algerian history; known to few Algerians today.

Motivated by a need to preserve the memory of her country’s struggle, especially from the perspective of its women, Drif decided to commit her experiences to paper, publishing her memoir in 2017.

Her memoirs of her time in the Army of National Liberation (FLN) recalls the ways in which Algerian women used their femininity to aid the cause of liberation, turning the traditional ululations of Arab and Amazigh women into a warrior’s cry to sow fear among French occupiers.

Drif takes the reader to the Casbah and the heart of the resistance, providing a precious account of the role women played in Algerian independence.

The book covers Drif’s early decision to join the resistance, her rise through the ranks of the FLN and her role in the bombing of the Milk Bar, which killed three people.

In 1957, French authorities arrested Drif, along with Yacef Saadi, sentencing her to 20 years in prison but freed her in 1962 after the war ended.

2. Algiers, Third World Capital by Elaine Mokhtefi

Born Elaine Klein to a secular Jewish family in New York’s Long Island, Mokhtefi would go on to capture Algeria’s transition from a French colonial territory to becoming the capital of third world resistance against European imperialism.

Her 2018 memoir Algiers, Third World Capital captures Algeria’s history immediately after independence.

Mokhtefi spent 12 years there working as a journalist but her first brushes with the independence movement came not in North Africa but in Paris, where she moved in 1951.

On May Day in 1952, the American met Algerian labourers excluded from a French trade union march, leading to her recognising the “lie” of the French national motto of “liberty, equality, fraternity”.

From then on, Mokhtefi became an advocate of Algeria’s freedom, becoming close with the post-colonial philosopher Frantz Fanon, who would later succumb to injuries sustained fighting the French in North Africa.

Her memoirs detail her move from New York to Paris to Algiers, but her story comes amid the backdrop of Algeria’s own.

She details, for example, the 1969 Pan-Africanist Festival of Algiers, a conference in the Algerian capital bringing together anti-racist and anti-colonial figures, from across Africa, the Middle East and even the US. Notable attendees included Black Panthers Eldridge Cleaver and Stokely Carmichael.

Mokhtefi’s role as a journalist and bilingual skills in English and French allowed her to witness historic scenes from a unique perspective: that of a white American woman, sometimes at the heart of the action, sometimes not, but always a spectator.

In 1991, Elaine married Mokhtar Mokhtefi, a veteran of the war of independence and author of the book I was a French Muslim: a Memoir, which was translated by Elaine Mokhtefi herself.

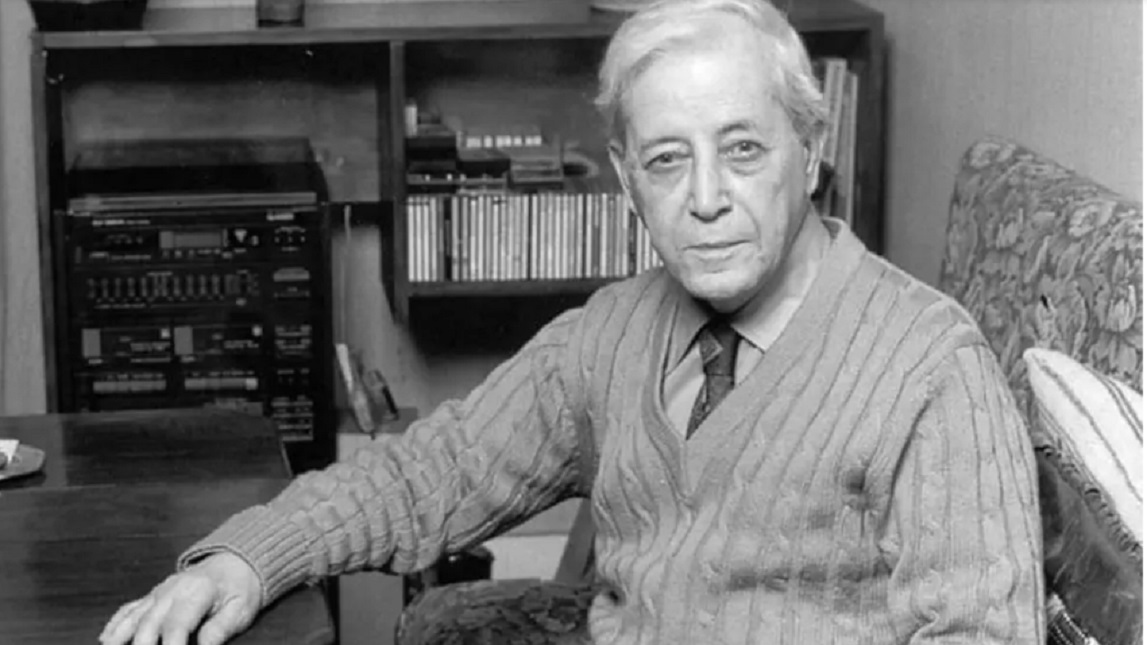

3. At the Cafe and The Talisman, by Mohammed Dib

Mohammed Dib is one of Algeria’s most famous authors, having published 30 novels, as well as collections of short stories, poetry and children’s literature, before his death in 2003 at the age of 82.

His most acclaimed work is The Algerian Trilogy, which is comprised of 1952’s La Grande Maison (The Big House), 1954’s L’incendie (The Fire) and 1957’s Le Metier a Tisser (The Weaving Loom). The trilogy has been adapted for the small screen, starring the late actress Chafia Boudraa and singer Biyouna.

Dib was among the first Algerian Francophone writers who focused on relaying a realistic account of the Algerian experience; centring stories around regular Algerian characters had been rare until that time.

At the Cafe was published in 1957 during the Algerian War of Independence and The Talisman, published in 1966 after independence, was translated into English by C Dickson.

The two collections of short stories are good examples of Dib’s unique writing style, one that seamlessly shifts from a verite approach that addresses the realities of colonialism to a more nebulous style, which could be described as magical realism.

Each of Dib’s characters form a singular part of the diverse mosaic of Algerian life.

In one story, an unemployed man spends his days in a cafe to kill time and avoid being around his family, for whom he cannot provide.

Another describes the emerging social consciousness of Algerian peasants oppressed by French colonialists, an awakening that is mirrored mystically in the rising of the land itself.

Politics is at the forefront of these stories but the later work shifts more towards esotericism. At the Cafe ends with a character moving away from a rational reality towards a more fuzzy, dreamlike state, in which he tries to connect with his ancestors. The stories in The Talisman further indulge this enigmatic approach.

4. Children of the New World by Assia Djebar

Assia Djebar, the pen name of Fatima Zohra-Imalayene, is one of Algeria’s most distinguished female writers, with at least eight of her books translated into English.

Translated by Marjolijn de Jager and published by Feminist Press, Children of the New World is typical of her style, which centres female characters who are drawn from her own life experiences.

The author’s third novel offers a kaleidoscopic and nuanced image of revolutionary Algeria.

Set in an unnamed city, later identified as Blida, Algeria’s “city of roses”, in May 1956, the book explores a single day in the life of five main female characters and four male ones.

As the book’s title and setting during the Algerian War of Independence suggest, the story follows the characters as they entertain the possibility of a new reality; one in which they are free from French colonisers but also one in which the restraints placed on women by both colonial and Algerian society are lifted.

The characters' stories intersect as the labyrinthine plot unwinds, revealing the divisions found within Algerian society at the time. Youseff, character Cherifa’s second husband, joins the resistance to the French, while Hakim, the police officer, remains loyal to the colonial authorities.

Djebar’s eye is equally fixated on the role of women in the independence movement; Cherifa wears the veil but refuses motherhood and has to put up with male stares, Algerian and French, as she makes her way to a town centre to warn Youseff about a looming threat.

Thousands of mourners, including leading politicians, attended Djebar's funeral in her hometown of Cherchell after her death in 2015

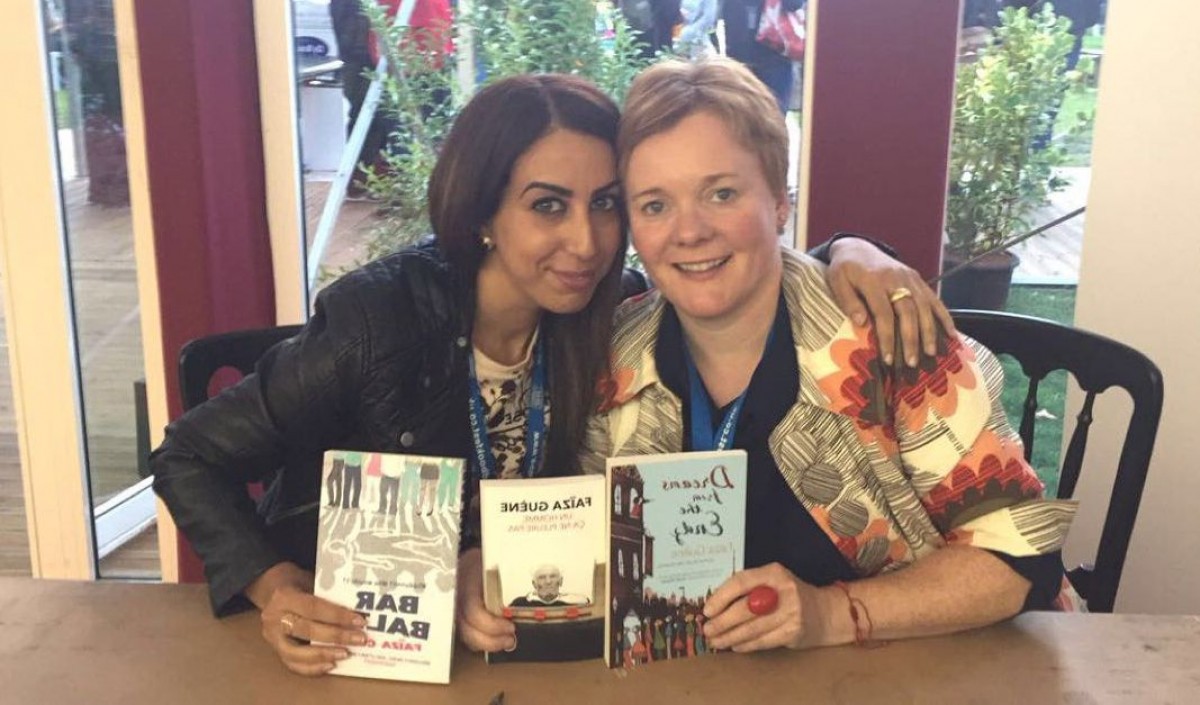

5. Discretion by Faiza Guene

Faiza Guene’s latest novel Discretion was translated by Sarah Ardizonne and published by Saqi books.

Whereas all of the author’s previous books were stories set in Algeria, Discretion is set in France and is populated with a cast of French-Algerian characters.

The story revolves around Yamina, an Algerian woman who lived through Algeria’s struggle for independence and the post-independence period, during which Algerians suffered extreme poverty.

Guene takes up a time-shifting approach, jumping from Yamina’s present in 2019 and her past in 1954; the latter serving as an expositionary tool to explain the character's current disposition.

The book essentially deals with the issue of lingering trauma resulting from colonialism and the related racist discrimination Algerians in France face, as well as the generational divide in dealing with the issues.

Yamina gets married and moves to France with her husband, a place where she feels invisible and like a guest. But for her children, it’s a different story.

Her daughter Hannah is the polar opposite of her discreet mother.

Angry, confident and defiant, she declares: “We’re not ‘guests’! Did you ever receive an invite? Because I didn’t! […] We were born here! And our coming here was hardly a coincidence!”

In popular parlance, children of the North African diaspora are referred to as being from an "immigrant family". Hannah sets out to correct that perspective. To her the Algerian diaspora in France is not the result of immigration but of colonisation.

Yamina, however, struggles to be as outspoken as her daughter; repressing her anger and becoming invisible are survival skills learned during her childhood under French colonial rule.

The flame of her anger never disappears though and is instead passed down to Hannah, in whom it lives vicariously.

Guene’s tender novel describes how “discretion” can be used as a weapon, a means of resistance for a generation that could not afford to be as loud as the one that succeeded it but also does not want anger to turn into a hatred that consumes its children.

Discretion’s opening epigraph is a quote from James Baldwin's The Fire Next Time, which reads: “It demands great spiritual resilience not to hate the hater whose foot is on your neck, and an even greater miracle of perception and charity not to teach your child to hate.”

The author dedicated the novel to her father Abdelhamid Guene, who she says died of “discretion”.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.