How the killing of a Palestinian youth became a play read by African Americans

Last month marked the 20th anniversary of Israel’s killing of 17-year-old Asel Asleh, a Palestinian citizen of Israel whose youthful idealism had prompted him to join the Seeds of Peace leadership camp with fellow Palestinians, Israelis and Americans.

Asleh was one of 13 unarmed Palestinians shot by Israeli security forces inside Israel that month, along with dozens of other Palestinians in the occupied West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza as protests erupted across historic Palestine in what became known as the Second Intifada. He died while still wearing his green Seeds of Peace T-shirt.

She uses her friend's story to launch an international conversation about all families, from Palestine to the US, who have lost loved ones to state violence

In 2016, after years of interviews with Asleh’s sister, Nardeen, and others, American playwright and activist Jen Marlowe, who was a Seeds of Peace camp counsellor, produced a play titled There is a Field about her friend’s murder and the Asleh family’s failed attempts to obtain justice.

This year, Marlowe completed a documentary based on that play. It premiered in Palestine on 2 October, the exact anniversary of Asleh’s killing, and in the US on 18 October, with additional virtual screenings during the month and discussions with activists, organisers and members of the Asleh family. The US premiere featured a powerful, inspiring talk with, among others, the victim’s brother, Baraa Asleh, and Gwen Carr, the mother of Eric Garner, whose dying words, “I can’t breathe”, have become a rallying cry against police brutality.

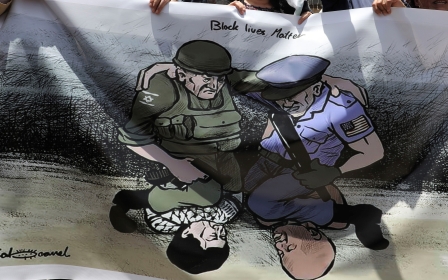

The documentary is a filming of one reading of the play, performed in New Mexico by Black Lives Matter organisers and activists, and interspersed with archival footage from that fateful day in October 2000 and its aftermath. It includes commentary on the many similarities between the circumstances of Palestinian citizens of Israel and Black Americans, as each community confronts systemic racism and a state apparatus that deems them undesirable and disposable.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

This is not to suggest that the film, or the conversations around law enforcement, violence and systemic racism, are highbrow abstractions. Marlowe excels at detailing the personal, the intimate, the human. Her work, in this film and elsewhere, is a subtle critique of the fact that political movements can obscure personal tragedy for the purposes of large-scale mobilising: murdered sons, brothers and close friends often become symbolic martyrs belonging to the community, with little opportunity for their closest relatives to mourn.

In a heartbreaking scene, as the procession for Asleh’s funeral goes through their village, the crowd blocks Nardeen’s view of her beloved brother, while Baraa can’t even catch a glimpse of the casket and has to watch the procession on television instead.

Supremacist systems

Marlowe uses such private details to launch heartfelt conversations among the actor-activists and the audience, who are able to recognise, in the plight of the Asleh family, aspects of their own pain and loss, as they, too, must confront a supremacist system bent on killing them.

She uses her friend’s story to launch an international conversation about all families, from Palestine to the US, who have lost loved ones to state violence, and all people whose lives have been shattered by callous, murderous racism, and the indifference of the justice system to their plight.

The film gives us an intimate look into one bereaved family, humanising individuals whose pain is routinely glossed over by western media. But There is a Field is also much more than a documentary, and more than the story of one martyr and his family. It is a prime example of “artivism” - art for social justice, and for building solidarity through storytelling.

The commentary from the Black Lives Matter activists is poignant, as they articulate the fundamental reasons for transnational solidarity and joint struggle. One actor put it best as she explained that, as a Black teenager in the US, she always felt she had a target on her back - and she realised, through Asleh’s story, that Palestinians throughout their historic homeland feel the same way.

There is a Field was produced by Donkeysaddle Projects, which Marlowe founded, and which - until the Covid-19 pandemic and ensuing lockdown - had been facilitating a series of intensive theatre-based community residencies and performances, using the play as a framework for deep political education and movement-building. The project’s website notes that it aims to “build Black-Palestinian solidarity, and strengthen local Palestine organizing and cross-movement building”.

Interconnected battles

Asleh’s story, as told by Marlowe, is connected at once to the struggle for Palestinian liberation, Indigenous sovereignty on Turtle Island, and the Black Lives Matter movement. It is a strong denunciation of the pattern of unarmed youth - Black and brown and Arab - being killed with impunity by a hyper-militarised police force that sees them as threats or criminals, not as young idealists or teenagers simply walking home from the store.

The play also critiques Seeds of Peace and similar encounter programmes between Palestinian and Israeli youth. Nardeen’s frustrated comment to her Israeli coworker that “I didn’t move to Israel, Israel moved to me” recalls the settler-colonialism of Indigenous North America, but also Malcolm X’s statement that “we didn’t land on Plymouth Rock, Plymouth Rock landed on us”.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.