London on fire: This could be a Titanic moment for our ruling elite

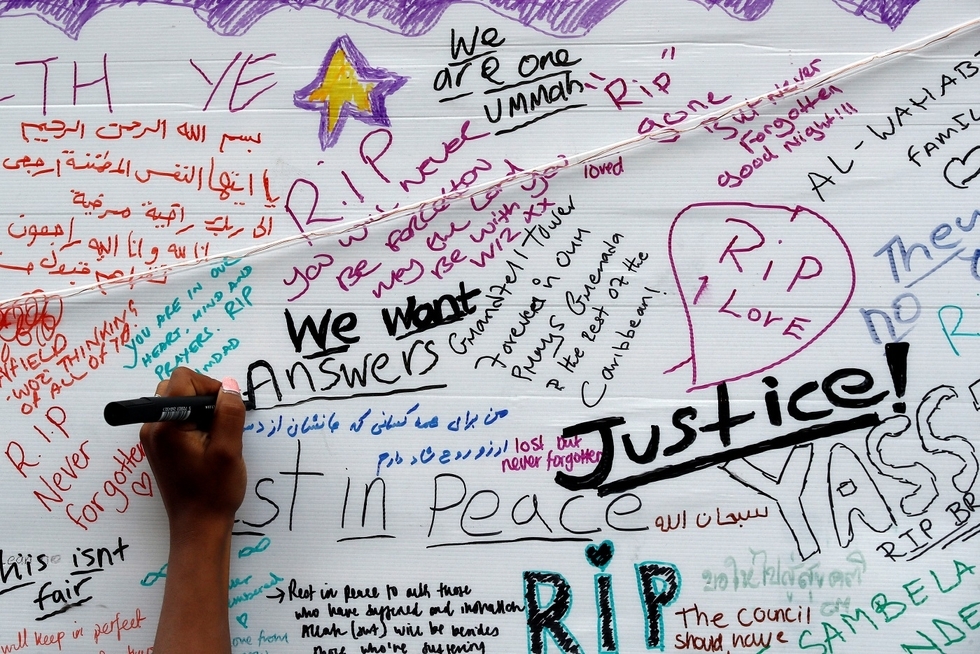

“I remember watching the film Titanic when I was younger & thinking ‘wow I cant believe they put the poor people at the bottom without life jackets and lifeboats to save them.’ This feels like the housing equivalent.”

These words, written on the wall of condolences for the victims of London's Grenfell Tower fire, describe how two disasters, separated by a little over a century, reveal the way class and wealth still determine who lives, and who dies.

As Mark Twain almost said, history doesn't repeat itself, but it rhymes.

While the world is dramatically different today than a century ago – in terms of technology, politics, society and improved longevity for many – in one way, things are similar: the gaping divisions between and within countries appear to be reaching breaking point.

Watch the fury and terrible grief of a young member of the El-Wahabi family (43.10 onwards) who lost five relatives in the Grenfell fire and you get a sense of lethal injustice that now demands redress.

Return of crisis

A century ago, the last of the ancien regimes were collapsing amid a world war. In 2017, the imperial system, now led by a pre-eminent United States, is once again in crisis. Millions are fleeing war and chaos, like 22-year-old Syrian refugee Mohammed Alhajali, who thought he had found safety in London only to die in the Grenfell fire.

Meanwhile, Kensington and Chelsea's deputy leader and councillor for housing, millionaire property developer Rock Hugo Basil Feilding-Mellen - whose very name speaks of ancient class privilege - was dodging questions.

As in the Twain-coined Gilded Age, excess wealth is unbounded. Jeff Bezos, the boss of internet distribution giant Amazon, asks his Twitter followers how he should dispose of his $84bn fortune.

As in 1917, we can see in the rapid turning of events the signs of a new revolutionary moment – the current order is breaking down, and millions have had their eyes opened and are demanding a new one. But it is too early to say what that new order will be.

A century ago, the Russian Revolution threatened to pull the tsarist empire out of the Great War, at that point grinding towards its final denouement. The war had huge unintended consequences – a socialist revolution in Russia, the collapse of the German monarchy, and the demise of the feeble Turkish and Austrian empires. It's the same year that brought the world’s most dynamic economy, the United States, onto the world stage as a new, reluctant imperial power, when Woodrow Wilson sent troops to join the Allies.

Regimes fall

In the second decade of the 20th century, revolution swept away the old order in Mexico, China, Russia, Turkey and Germany. In our own decade, the failed Arab and North African revolutions of 2011 may simply be the first phase of a revolt that will erupt again just when no one is expecting it.

Look at the mass protests in Tunisia and Morocco today, and the unrest in Saudi Arabia’s eastern province, and the signs of a second wave of uprisings are already there.

In 2017, the US easily overshadows its nearest competitor, China, both militarily and economically. And yet Washington and its allies are thrashing around incoherently in an attempt to shore up their financial and economic dominance they have enjoyed for so long.

And the major threat they face is not external, as to a greater extent it was in 1917. It is not the terrorism that they are fighting on multiple fronts. No, the crisis they face is systemic: economic decline, social polarisation, the loss of legitimacy and political divisions among its allies, including the UK, the EU and the oil-rich Gulf states.

The enemy within

If there is a revolutionary threat in 2017, it is not Bolshevism, but a group of old left-wing politicians – Sanders, Corbyn, Melenchon - and their politically conscious young followers who are defying the punditry by storming the barricades of mainstream political authority in Europe and America.

The economic orthodoxy around neoliberal globalisation and the dominance of financial markets is under attack. Traditional right-wing and centrist parties are losing ground to nationalists and populists, and are unable to articulate a vision that voters want.

Although the process is uneven across countries, as the victory of Emmanuel Macron in France’s presidential election shows, the direction of travel is unmistakable. The failure of the radical left to make the second round of the French presidential poll led a month later to parliamentary elections in which an unprecedented 57 percent of voters boycotted the polls.

In 2017, the taste of a new upheaval, a new militancy, and a wobbling of the authority of the ruling elites is in the air, as it was a century ago. In America, it has been temporarily diverted into Trumpism, which has brought about a split in the ruling class, ironically played out through a Russians-under-the-beds hysteria. (While Russia has undoubtedly enjoyed America’s strategic paralysis and held its own in various geopolitical spheres, this is a crisis of America’s making.)

Washington’s pursuit of Trump’s nefarious Russian ties contains powerful echoes from earlier moments of national psychosis, such as President Wilson’s campaign launched in 1917 against the internal threat from German agents, anarchists and Bolsheviks, the witch hunts of the McCarthy era, and the post-2001 clampdown on Arab Americans. Consistently, the scale of the drama is inverse to the actual threat.

Crisis of authority

In 2017 Britain, a crisis of central authority has unfolded with a series of referendums and elections that have divided the nation and given an opening to Jeremy Corbyn’s surprise emergence from backbench rebel to potential prime minister.

As a longtime critic of Gulf dictatorships, Corbyn may also be secretly enjoying the crisis that has blown up among the ruling monarchies over Qatar's alleged support for terrorism - bringing disorder to the one part of the Middle East that so far has avoided violent upheaval.

We are in the early phase of a systemic crisis, but, as in 1917, history appears to be speeding up – and this is not just because of social media. A kaleidoscope of surprising crises unfolds and bewilders as we await the next bloody spectacular or election result that none of the experts predicted.

As William Goldman once said about Hollywood, nobody knows anything. And that has never been truer of politics today, turning the mainstream media and analysts into a laughing stock. There is a new kind of nervousness about the threat of disorder among our commentariat.

These are new times. 2017 is only half way through. In June 1917, the Russian October revolution, that shattering event that changed the course of the 20th century, was still four months away. Anything can happen.

- Joe Gill has lived and worked as a journalist in the UK, Oman, Venezuela and the US, for newspapers including Financial Times, Morning Star and Middle East Eye. His Masters was in Politics of the World Economy at the London School of Economics.

The views expressed in this piece belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Image: A detail of the memorial wall after the fire which destroyed the Grenfell Tower block, in north Kensington, West London, Britain on 15 June 2017 (Reuters)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.