Why we shouldn't tear down statues of appalling historical figures

The discussion on race is arguably one of the simplest and the most difficult. Simple, because it speaks to one of the most basic traits a human being acquires; yet extremely difficult because political, ideological and commercial monoliths show how inequality yields enormous profits and solidifies positions of immense power and authority.

The world, gripped by a pandemic that has seen the most powerful countries exposed as inept and incompetent in saving the lives of their own, has watched in disbelief as a Black American was killed by a white police officer yet again.

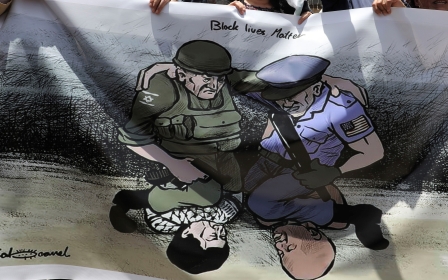

Despicable symbolism

The image of a white, fully armed figure of authority sitting with his knee on the neck of an unarmed, fully restrained Black American, slowly draining him of life while staring boldly into a camera lens, was despicably symbolic. Nothing could have better captured the true dynamic between Black and white. Banksy couldn’t have produced a more telling piece of art.

The protests that have swept the US, the UK and many other countries around the world show that decency continues to prevail over barbarity. At the same time, a broader discussion has unfolded over the maintenance and preservation of statues of historical figures.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

George Floyd has seemingly awoken us to the fact that our history is littered with some of the most gruesome acts imaginable, perpetrated by people often regarded as national treasures

Scattered throughout capitals and major cities of the Western world are commemorative structures of figures from yonder years, described as gallant, brave, wise and generous - but many of whom, it turns out, dabbled quite a bit in the slave trade and crimes against humanity of various sorts.

This jolt of realisation fuelled by the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis opened our eyes to the fact that even the revered former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was himself of the kind who didn’t mind the odd mass murder, gassing stubborn adversaries or speaking of other nations as “cockroaches” and “beasts”, and treating them as much. Admiral Horatio Nelson presents another example.

Indeed, it turns out that there are scores of such statues and names adorning public squares, buildings and throughways across the UK. From Oxford University to the Museum of London Docklands, George Floyd has seemingly awoken us to the fact that our history is littered with some of the most gruesome acts imaginable, perpetrated by people often regarded as national treasures and icons of patriotism, heroism and triumph.

Churchill's war-criminal mode

The calls to deface and ultimately remove such statues is not only understandable, but commendable. I must confess that I only discovered the story of Churchill gassing the Kurds in Iraq after stumbling across historian Charles Townshend’s 1986 essay while organising for London’s two-million-person march against the war on Iraq in 2003.

Since then, I’ve learned more and more about how he easily slipped into war-criminal mode against various adversaries, expressing deep irritation towards members of parliament and ministers who thought otherwise. I have consequently taken a deep dislike to the man, regarded by many as the most British of British icons.

One might thus assume that I would cheer the removal of his statue, a prominent feature of London’s Parliament Square. Alas, no.

While I totally understand and greatly admire the calls by many to remove the respectability that slave masters and war criminals command by having permanent monuments in public spaces - visited by millions of the descendants of their victims annually - I fear that such removal would do away with an essential and indispensable part of our history.

I am not referencing the oft-repeated argument about learning from our past, valid as it might be. Rather, I am referring to the much-needed constant reminder that we - as a nation, society and establishment - celebrated these figures for decades and centuries, affording them the most prominent of spaces and the most celebratory of statements, while blissfully ignoring the litany of horrors they committed, and for which they became so prominent, rich and powerful.

Admitting ownership

I fear that we risk whitewashing our own collusion in the false penning of history, and our own role in turning a blind eye towards the crimes committed against countless innocent souls and defenceless nations across centuries of empire.

It would be so convenient to rip out selected pages of history books as an act of penance, but it would be far more impactful to keep those episodes prominent, to teach the young about how many of our nation’s forefathers committed heinous crimes - and that we continued to celebrate them until a Black American by the name of George Floyd was murdered in the US.

To move on, and to begin to address the crisis of race and racism, demands an admission of ownership of our past and the fact that we turned a blind eye towards the dark episodes of our history for far too long.

Otherwise, society will be able to wash its hands of having played any part therein, instead pinning it on a historic figure and trashing or hiding their statue from public view, decades or even centuries later.

If that is allowed to happen, I fear another grave wrong will occur yet again.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.