Russia report: UK's dance with the Kremlin comes home to roost

A long-awaited report by the British parliament's Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC) on Russian activity in the UK has been finally released after months of delay.

It contains significant and concerning evidence pointing to Russian interference in British politics, but, most importantly, it constitutes a brutal indictment of the positive attitude maintained for years by the British political and financial establishment towards such activities.

Indeed the report's real shocking revelation seems not so much about Russia’s interference, but rather how such interference has been largely facilitated by the British establishment.

When the report says that consecutive British governments have "welcomed the (Russian) oligarchs and their money with open arms, providing them with a means of recycling illicit finance through the London 'laundromat', and connections at the highest levels with access to UK companies and political figures," it is difficult to avoid a sense of bewilderment.

The report's real shocking content, however, seems not about Russia’s interference, rather how such interference has been facilitated by the British establishment

Facing a similar shocking indictment, any Italian government - in a country whose political institutions have been frequently accused of collusion with organised crime - would have immediately resigned. It should not be surprising, then, that the the report's release has been delayed for nine months, long after last December’s general election. Its release before or during the campaign would have been a damaging embarrassment to Prime Minister Boris Johnson's election chances.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

A second contentious issue is what many considered to be the report’s possible omissions concerning the relationship that some members of Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s inner circle may have maintained with the inner circle of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Last November, Labour's then shadow foreign secretary Emily Thornberry accused the government of withholding the report's publication because of the questions it would raise about the prime minister's chief aide Dominic Cummings' time in Russia. "Questions about…his relationship with the Oxford academic Norman Stone and the mysterious three years he spent in post-Communist Russia aged just 23," Thornberry told the Commons, "and the relationships he allegedly forged with individuals like Vladislav Surkov, the key figure behind Vladimir Putin’s throne."

Surkov is a personal advisor to Putin who is widely regarded as one of the creators of post-truth politics where facts are relative. He recently said that the Putinist system of government would be the "ideology of the future" and added that Russia was "playing with the West's minds".

Cummings has received UK security clearance. It is at least an open question, worthy of public examination and scrutiny, about what links Cummings may have had with Surkov, and how far their relationship went. And yet contacts which a senior government advisor has had with a key backroom figure in the Kremlin are not mentioned in the report at all. How so?

A further embarrassing aspect presented by the report is that on crucial topics, like Brexit.

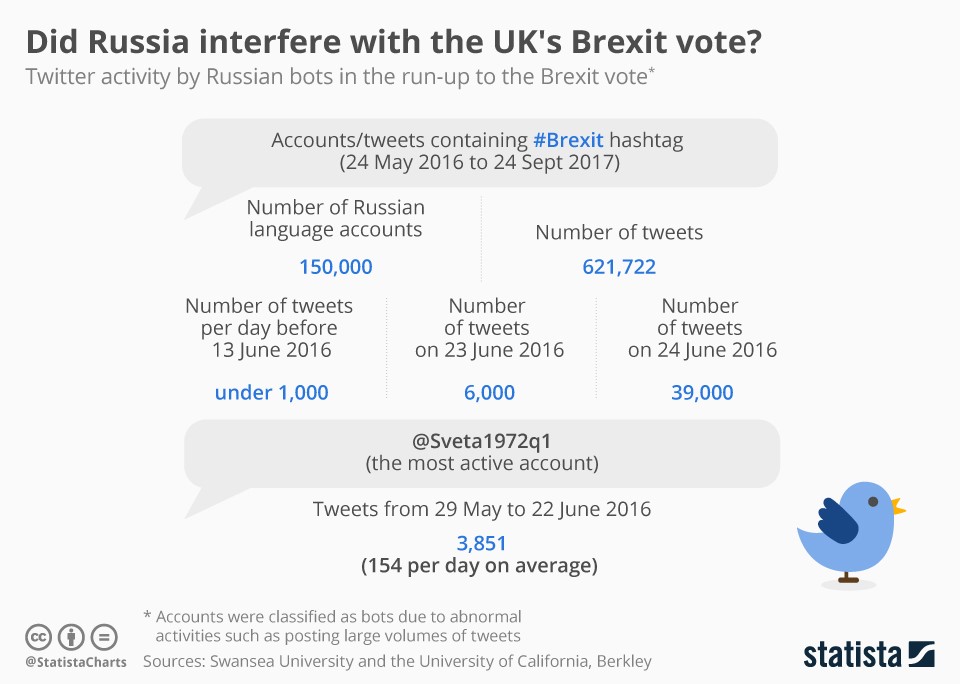

Although the report did not come to a conclusion on whether Russia tried to influence the Brexit vote, it cites "open source" studies which pointed to "pro-Brexit or anti-EU stories on RT and Sputnik, and the use of 'bots' and 'trolls', as evidence of Russian attempts to influence the process".

Boris Johnson, his Conservative Party, and the wider Leave supporters were on the same page with the alleged Russian aim in providing a serious blow to the European Union.

Yet before Brexit, the hard facts are that in the 15 years of the Anglo-Russian thaw, not only did all British authorities, but especially MI6, know about the laundering of Russian money in the London property market -they actively encouraged it.

The security services resettled several Russian oligarchs, most notable of whom was the former Russian government official Boris Berezovsky. The latter, a former mathematician, was found dead in 2013 at his home in Windsor in circumstances which are to this day disputed. Berezovsky was a pioneer in the Russian art of money laundering, creating a web of shell companies to disguise ownership and money transfers.

Incorrect assumptions

While the aim here is not to challenge the report’s conclusions, some of its basic assumptions appear nevertheless incorrect, misleading, and unforgivably generic. In its introduction the report says:

“In the 1990s and early 2000s, Western thinking was, if not to integrate Russia fully, at least to ensure that it became a partner. By the mid-2000s, it was clear that this had not been successful. The murder of Alexander Litvinenko in 2006 demonstrated that Russia under President Putin had moved from potential partner to established threat."

Fifteen years of Russia-Western relations summarised by mentioning only one admittedly notorious incident, Litvinenko's murder. No mention of the effects of Western economic shock therapies in Russia during the late Russian President Boris Yeltsin's years; no reference to how Russia may have perceived Western interventions in Kosovo in 1999 or in Iraq in 2003; no hint of how Nato’s eastward expansion or the Western-triggered colour revolutions may have somewhat fuelled what the report described as “Russian paranoia”; no recognition of Russian cooperation against terrorism after the September 11 attacks and through the Nato-Russia Council set up in 2002.

The West's Russia problem

In February 2007, in a speech at the Munich Security Conference, Putin gave a serious warning about the quite unsatisfactory trend the relationship between Russia and the West was taking. He listed some Russian concerns over Nato's expansion and the West's excessive use of force outside the legal boundaries set by the United Nations.

He was ignored.

This is not to claim that all of Putin’s arguments were valid, but simply to emphasise that sometimes putting yourself in your adversary’s shoes may be necessary and useful if the intention is to reach a mutual understanding and avoid increasing tensions.

The West's problems with Russia did not started with, or cannot be summarised by, Litvinenko’s murder, as the British parliament's ISC seems to hint.

Their roots are far older.

According to Russian perceptions, since the fall of the Soviet Union, Western nations have carried out repeated, systematic and probably unnecessary interference in Russia and its "neighbourhood", culminating with the Ukrainian crisis in 2014.

The sooner this fact is recognised and dealt with accordingly, the better.

What qualifies as intervention

In more general terms, the naked truth is that all countries attempt to interfere in other nations’ politics. Russia is no exception. However, it should be explained why, for example, Russia should be scolded for its diplomatic interference in Ukraine’s accession talks with the European Union in 2013, while pressure from the Trump administration that forced the UK to bar Chinese company Huawei from the UK"s 5G network should not qualify as interference?

It is becoming more and more incomprehensible to blame nations like Russia for certain questionable actions when some Western nations do the same

It's difficult to argue that since the end of the Cold War western nations did not carry out any interference in the politics of other countries and in their electoral processes.

Again, it is also difficult to claim that many of these operations were carried out only for the sake of democracy promotion. As for spying, the leading global network carrying out such activity is the notorious Five Eyes ring, an intelligence alliance comprising Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States, which does not spare even its own allies.

Last but not least, can it be seriously argued that Russia (or China) have the exclusive monopoly on carrying out dangerous cyber activities? True, some Western actions can be explained as mistakes committed in good faith, but this cannot become a widespread self-absolving justification.

It is becoming more and more unsustainable to hold nations like Russia responsible for certain questionable actions but absolve Western nations, who commit the same actions, from any kind of responsibility.

Other global and rival players may be paranoid, they may also be malign, but certainly they are not dumb, especially not Putin’s Russia.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.