Surrounded by fire: Why Starmer’s foreign policy problems are piling up

It’s usually a sign of a failing, end-of-the-line prime ministership when the incumbent becomes obsessed with foreign policy trips abroad.

So it was for Margaret Thatcher—who was actually removed while in Paris—and for Tony Blair and his government, lost with all hands in the sea of troubles that was the Iraq invasion and its consequences.

But Keir Starmer seems to have begun how others ended. As of 11 November 2024, Starmer had visited each of Belgium, Hungary, Ireland, Italy and Samoa once. He has also visited France, Germany and the United States three times each.

Starmer may, like his predecessors, be fleeing domestic political misery (his first 100 days being now infamously deflating, not least due to his opinion poll ratings). Although this is a case of early-onset political misery.

That’s 14 trips, nearly one a week since he became prime minister. And there’s more coming up with visits to Saudi Arabia and UAE next year. No wonder Starmer has earned the Westminster nickname "Gap Year Keir".

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

But the oddity is that Starmer is hardly moving into an international arena where he can strike a heroic pose, as Thatcher thought she was doing on the post-Cold War stage, or Blair thought he was doing in Iraq, until the realities caught up with him.

Indeed, Starmer’s international situation is at least as perilous as his domestic one.

'Special relationship'

First off, the hinge on which all UK foreign policy turns—the "special relationship" with the US—can rarely have looked so troublesome for an incoming British prime minister.

Donald Trump, as he has made abundantly and publicly clear, hates the Labour Party. He hates it in general ideological terms, he has long hated its Muslim mayor of London, and he detests the fact that Labour Party members went to work for Kamala Harris’s doomed campaign.

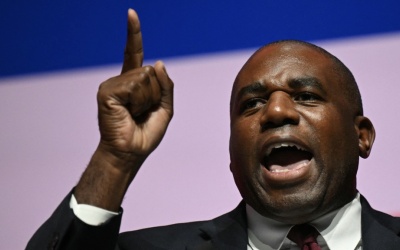

And Labour cabinet members, at least in their pre-office-holding, free-speech days, made it clear what they thought of Trump. And no one had been clearer than the new foreign secretary, David Lammy, who, before he was charged with the nation’s diplomacy, called Trump "a neo-Nazi-sympathising sociopath".

Lammy, not a mind to whom second thoughts come easily, has now done some FCO-inspired grovelling. But Trump is famously vengeful and petty, so it’s unlikely to rehabilitate him in the president-elect’s eyes.

Now, it might be said that this political animosity will be a marginal issue, and that the relations between states will survive the incompatibility of personalities and ideology.

But that may be wishful thinking, for there are matters of substance at stake that will trouble the alliance, perhaps more than it has been troubled since the Suez Crisis in 1956.

Trump is a protectionist and an isolationist. The US has not had a president like that—with the exception of Trump’s first presidency—since before the Second World War.

If Trump keeps his campaign promise—quite the "if," admittedly—then trade tariffs are coming. Aimed specifically, but not only, at China, they may hit the UK as well.

If they do, the already fragile UK economy will take a battering—£22bn, according to some experts. That’s the same scale as Chancellor Rachel Reeves’s alleged "black hole" in the national finances.

If the Trump tariff hit happens, the cost of living will ratchet up again at a time when workers have not recovered from that last spate of corporate price gouging.

Trump's isolationism

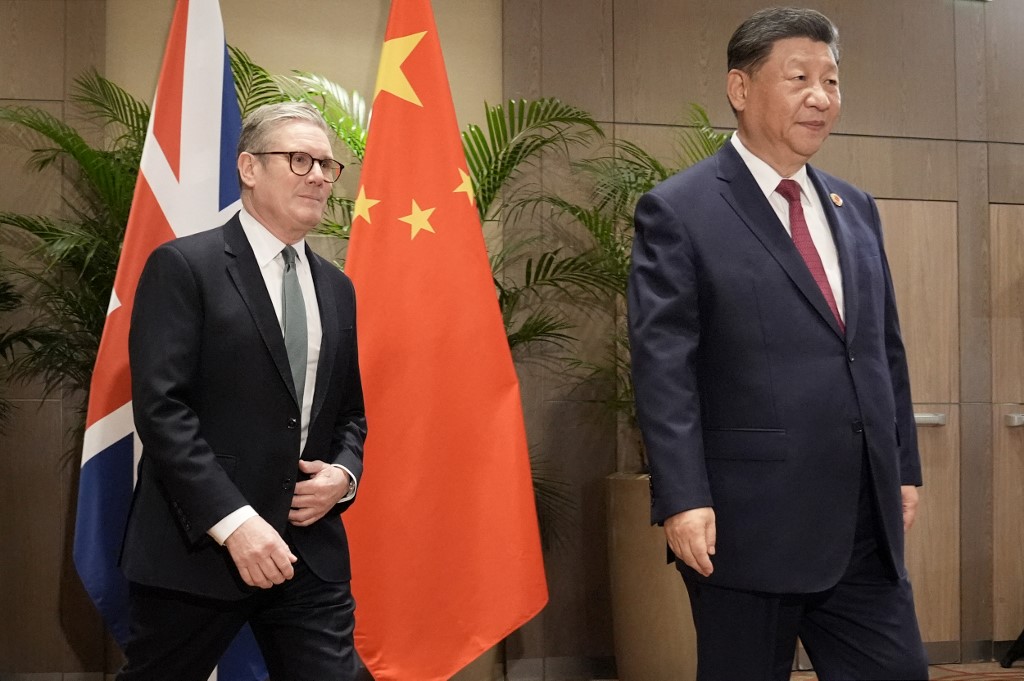

Even if Trump excludes the UK from his tariffs, there will be a price—likely the UK joining in with Trump’s trade war. And that, too, will be a costly option, as China remains the UK’s sixth-biggest trading partner, just after France and ahead of Italy and Spain.

Secondly, the Ukraine war will provide another stumbling block. Volodymyr Zelensky’s government is clearly losing the war, even though the cost to Russia is huge.

Trump has, in a typical boast, said he could end the war in a day. That is buffoonery, of course. But the isolationist in Trump and the realist in other members of the US foreign policy elite may coincide in the conclusion that now is the time to cut their losses in Ukraine.

The whole point of a proxy war is that you are supposed to defeat your enemy without engaging your own forces. Yet the war is increasingly looking like it can’t be won without direct, or at least more direct, western fire-power.

Trump may take another view and leave the British and Europeans to unravel the pro-Ukrainian ideology they have so carefully constructed as best they can

Starmer seems to have no qualms about that, as his advocacy of allowing Ukraine to fire British Storm Shadow missiles into the Russian interior demonstrates.

But Trump may take another view and leave the British and Europeans to unravel the pro-Ukrainian ideology they have so carefully constructed as best they can.

It’s quite something that the British establishment has managed to find itself at odds with the two major trade blocs that determine the shape of the British economy. But that’s where Trump’s protectionism and Brexit have left them.

Starmer really has no answer to this double danger. He will, of course, try and suck up to Trump. But there’s a limit to how far that can go. Starmer will never succeed in outbidding the real Trump sycophants like Nigel Farage and the dominant far-right leadership of the Tory party.

And it will hardly convince Trump’s well-developed ear for genuine obsequiousness.

As the most destructive war in Europe confounds the Ukraine hawks, Starmer among them, and as the trade war finds the UK ground between the rock of Trump's protectionism and the legacy of Boris Johnson’s Brexit, he may soon long to return to the relative warmth of a sceptical and disillusioned electorate in Britain.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.