Caribbean to 'Caliphate': On the trail of the Trinidadians fighting for the Islamic State

Editor's note: On Wednesday 29 March 2017, Trinidadian Islamic State fighter Shane Crawford was designated a terrorist by the US. Crawford, who has featured in IS propaganda material, is among at least 100 Trinidadians believed to have joined IS. This essay, originally published last year, explores the reasons why so many have made the journey to Syria.

PORT OF SPAIN - Joan Crawford was at home waiting for her son, Shane Crawford, to return from the police station.

It was October 2011 and scores of young people in the Caribbean nation of Trinidad and Tobago had been detained under state of emergency powers introduced by the government to tackle a surge in violent crime and gang activity.

But nothing could prepare her for what was to come.

“And then I get the call that they [the police were] holding him for plotting to assassinate the prime minister!” She breaks into an incredulous laugh and claps her hands.

A media frenzy followed.

"All they wanted to find out was ‘who is Shane Crawford?' I went by my mum, the radio was on and every station was the same ting [thing].”

Crawford was released without charge after two weeks. But four years later, in August 2016, he was back in the news under a different name: Abu Sa'd at-Trinidadi.

Claiming to be a sniper for the Islamic State (IS) group in Syria, he had been featured in an interview in the group’s Dabiq magazine, urging sympathisers back home to “attack the interests of the Crusader coalition", including embassies, businesses and civilians.

"I also say to you, my brothers, that you now have a golden opportunity to do something that many of us here wish we could do right now. You have the ability to terrify the disbelievers in their own homes and make their streets run with their blood," he was quoted as saying.

Crawford is one of more than 100 Trinidadians believed to have gone to Syria. With a population of just 1.3 million, Trinidad and Tobago ranks among the leading countries per capita whose citizens have travelled there to fight for IS.

But with IS territory imploding, the government in Port of Spain now faces the prospect of some of those citizens seeking to return. Others may also be coming home against their will. According to reports in August, nine Trinidadians were caught by Turkish authorities en route to join IS in Syria and are awaiting deportation.

Faris al-Rawi, the attorney general for Trinidad and Tobago, told MEE that the government was looking at possible measures introduced by other countries aimed at curbing these numbers, including detention, forfeiture of travel documents and citizenship removal.

“There are a number of jurisdictions that have been experimenting with these laws: Australia, Malaysia, Canada, the United States. These types of laws are recent laws; they're not entrenched long-standing laws and so there is still room for judicial guidance,” he said.

Yet citizenship removal legislation has been met with controversy in some of these countries. Earlier this year Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau revoked a bill introduced by the previous administration, which allowed for dual nationals to be stripped of their Canadian citizenship, emphatically stating “A Canadian is a Canadian is a Canadian”.

Al-Rawi conceded that such legislation could affect “enshrined fundamental rights”, and would need to gain large majorities in both houses of Trinidad and Tobago’s parliament.

Even then, he admitted, it could still be struck down by the courts for being “disproportionate or repugnant to the constitution".

'Other jurisdictions have been treating issues of radicalisation extra-judicially, which is not something that Trinidad and Tobago wishes to add to our arsenal'

- Faris al-Rawi, Attorney General

But he denied the proposals would go as far as some measures introduced in other countries, such as the UK’s ‘secret courts’, in which some evidence is withheld from those accused of involvement in terrorism, or Guantanamo Bay-style detention centres.

“Other jurisdictions have been treating issues of radicalisation extra-judicially, which is not something that Trinidad and Tobago wishes to add to our arsenal,” he said.

Al-Rawi and others also stressed that not everyone who went to Syria and now wants to return to the Caribbean should be treated as a security threat.

“What we should be telling militants is that if you leave the country, it will be more difficult for you to return,” Gary Griffith, a former minister of national security, told MEE.

However, referring to the wives and children of fighters, he added: “There are many who have returned from Syria who are not terrorists... it doesn't mean they are enemies of the state.”

East Indian, 'Black Power' and Nation of Islam influences

To find out why so many young Muslims have swapped the white-sand beaches of the Caribbean for the battlefields of Syria and Iraq, MEE traced Shane Crawford’s footsteps across Trinidad, the larger of the two islands just north of the Venezuelan coast that make up Trinidad and Tobago.

His mother lives in a tidy, two-bedroom rented house in Cunupia, a suburb of the burgeoning central city of Chaguanas.

Onion-domed mosques, the smell of rotis stuffed with curried duck, and roads with names such as Madras Road and Rashaad Avenue all point to an unmistakable East Indian and Muslim presence here.

This background is reflected in the diverse demographics of the modern nation of Trindidad and Tobago, which gained independence from the UK in 1962.

According to census data, the country’s Indo-Trini and black communities make up about 35 percent each of the country’s population. Other groups include Chinese, Christian Arabs (descendants of migrants from parts of the old Ottoman Empire, which are today Syria and Lebanon), French Creoles, Whites, Spanish, mixed-race people and Caribs, who are the islands’ indigenous people.

Diversity is also reflected in the country’s religious holidays, which include Eid al-Fitr, Diwali, Christmas and Hosay, a quintessentially Trinidadian take on the Muslim holy festival of Ashura.

Most of the population consider themselves Christians of various denominations, with Hindus making up just under 20 percent. Officially, about five percent of the population is Muslim although some put this figure as high as 10 percent.

There is evidence that there were black Muslim slaves in Trinidad and Tobago in the early 1800s, while the larger Indo-Trini Muslim community has existed since the 19th century.

The contemporary black Muslim community is a relative newcomer, putting down roots during the 1970s as a result of the influence of the Black Power and Nation of Islam movements in the US, yet it has made an indelible mark on Trinidadian history.

Islamist insurrection and gang wars

In 1990, about 100 armed militants affiliated with Jamaat al Muslimeen (Jamaat), a local organisation rooted in the black Muslim community, stormed the country’s parliament, holding the prime minister and other members of the government hostage for six days. It's an event that has been described as the only Islamist insurrection in the western hemisphere.

In more recent times, the streets of central Trinidad have been engulfed by violence as a consequence of the Rasta City vs. Muslims gang war, a long-running dispute that has left a slew of young men dead.

Joan Crawford, a single mother, raised her family of three boys and three girls in a house nearby. Shane was her last child. The family attended a Spiritual Baptist church, a charismatic offshoot of Christianity that combines traditional African spirituality with Christian teaching.

'I started to cry because I said I would never see him again and he said "Mum, we will meet inshallah in Jannah [paradise]"'

- Joan Crawford, Shane Crawford's mother

But growing up in this part of Trinidad meant that Shane was exposed to Islam from an early age. “There was a Muslim teacher at his school he used to talk to,” she said. “He was always interested in Islam from the school days.”

She broke into a bright smile as she recalls the close bond they shared.

“We’re playing Scrabble, but he was beating me. He was always leading. I tell him: 'I'm going to make a word' and he always tell me about this up to this day. I put ‘foxtrot’.

“He says: ‘Mum, but that is not a word.’ I say: ‘Well, that is my word.’ He would always say: ‘Mummy, you cheat. That is not a word.’”

Like many young children, Crawford enjoyed playing video games, such as Mario Kart, on his Nintendo console. He also liked war games.

A copy of his CV shown to MEE by his mother revealed him to have been an able student and competent worker. He received a pass in six of the subjects he took for his 16+ exams, allowing him to go to college while working at a call centre where, during the course of two years, he was promoted three times.

Then, one day in 2005, Crawford came home and told his mother that he had become a Muslim and that she needed to cook halal meat. Though at first apprehensive, she learnt to accept her son’s decision. After a few years she became a Muslim herself.

'You are branded a terrorist'

Crawford was already known to police when he was detained in 2011 on suspicion of involvement in the alleged assassination plot, having been arrested earlier in the year on suspicion of weapons possession, but the charge was dropped after he spent three months in prison on remand.

A police character reference from the time seen by MEE confirms that Crawford did not have a criminal record.

While the alleged plot made international headlines, locally it was met with widespread scepticism. Muslim leaders appealed for more evidence. Keith Rowley, the current prime minister - who was then the leader of the opposition - dismissed it as “hysterical, political expediency”.

But Joan Crawford said that Shane’s arrest had affected how he was perceived by others.

“It was all over the world. And it's not like the government ever came out and said they made a mistake, they never did that,” she said. “And after what happened, remember, you are branded a terrorist.”

Several of the men held as part of the alleged plot have since left for Syria, but Joan Crawford is unsure whether her son’s treatment was a major factor in his leaving.

“Maybe it has something to do with it. I don't know. You can't tell somebody's mind,” she said.

In the two years between his release and going to Syria, Shane found it increasingly difficult to find work. He did a few odd jobs such as selling furniture, while he was forced to close a fish stall he had briefly opened on a busy main road after the delivery truck broke down.

Joan, who wore a black hijab that reached down to her elbows atop a lime green abaya, said she had no idea her son was going to leave, but that in hindsight he was spending more time with her.

“Yeah, he was hugging me more. As he came in, he would come straight to my room and hug me... he would come and lie on the bed with me, watch whatever movie I'm looking at.”

She hadn’t heard from Shane in a few days when in December 2013 she got a call on Skype. It was Shane and he was in Syria along with his first wife (he had two wives) and their son Yusha.

“I started to cry because I said I would never see him again, and he said: ‘Mum, we will meet inshallah in jannah [paradise].’”

He also explained to her his reasons for leaving: “But this is what I choose, this is my choice. [In Syria] they are raping my sisters and they are killing my sisters and their children.”

Though Joan Crawford was unhappy that she did not get to hug and give her son salaam or peace before he left, she accepts the path he has taken and does not believe he will come back.

But there is another part of Shane Crawford’s story that his mum was unaware of.

“When he became a Muslim, I didn't know about his friends,” she said.

Led astray by 'Sheikh Google'

In order to learn more about the circle of friends that Crawford kept, I headed to the region known as Trinidad’s "Deep South".

The journey took me past the flare-lit chimneys of the country’s largest oil refinery close to San Fernando that has turned this country into an industrial powerhouse and one of the wealthiest in the Americas. I then turned eastward to Princes Town, so-named after a visit there by Queen Victoria’s grandsons in the 19th century.

I had gone there to meet Umar Abdullah, a Muslim leader who knew Crawford and was involved in the Jamaat coup in 1990.

We sat down to talk in a modern shopping centre complete with air-conditioning and faux-marble tiles where he runs a dawah stall so that non-Muslims can learn about Islam.

The colourful leaflets on offer are the sort you might see in the corner of a busy high street in London or Birmingham, and range from “Women’s rights in Islam: respected, honoured, cherished” and “A brief introduction to Islam” to “Islam is not a religion of extremism”.

Abdullah, who wore a black turban that tailed off down his back, and has a long greying beard that sat just above the collar of his black and grey shirt, told MEE that his ex-flatmate Fareed - who also left for Syria – had first introduced him to Crawford.

They all attended the Umar ibn al-Khattab mosque in the south-eastern Trinidad town of Rio Claro, which is particularly popular with black ‘revert’ Muslims.

But Crawford, Fareed and the other four members of the circle wanted to further their Islamic studies and so took to "Sheikh Google" as Abdullah calls it.

They were also influenced by Abdullah el-Faisal, a preacher who was imprisoned and subsequently deported to his native Jamaica from the UK in 2007. His tapes had first gone viral in Trinidad and Tobago in the 1990s, but his call to arms have continued to echo through the years and across the Caribbean.

The 49-year-old says that the group imbibed el-Faisal to the point where they became exclusivist in their reading of Islamic texts. Verses “that led toward jihad would be referred to in a way to justify their actions”, he said.

Things came to a head for the group in February 2010 when a Rio Claro mosque regular was shot dead. Crawford and his circle appealed to the imam for permission to avenge the murder, making their case with a dossier of Islamic verses.

The imam refused, citing their lack of Islamic knowledge. After what Abdullah describes as “distasteful exchange of words”, the group broke away from the mosque.

They would now meet at various mosques in and around Port of Spain. Later that year, the same group were arrested over the alleged plot to kill the prime minister. A few years after that, they were all in Syria.

Yet while Shane Crawford’s reading of texts may have provided a religious pretext for his going to Syria, Joan Crawford and Umar Abdullah both say there was an underlying political grievance that played a crucial role.

Abdullah explained that for Crawford, the global Muslim community or the ummah "is one body, one must cure the pain, bring some cure and remedy".

Citing the suffering of Muslims in “Chechnya, Burma, Sabra and Shatila [the latter two locations being Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon where Christian militias backed by the Israel army massacred hundreds of people in 1982 during the country’s civil war],” Abdullah believes Crawford was motivated to take up arms because “there was no one to answer the need to stand up for Muslims”.

Joan Crawford said that her son had always wanted to study Islam and live in an Islamic country. When Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, IS’s self-styled caliph, called on Muslims around the world to immigrate to IS-held territory, Shane Crawford felt duty-bound to respond.

“One of our goals was to eventually make hijrah – when we had the ability to do so – and join the mujahidin [fighters] striving to cleanse the Muslims’ usurped lands of all apostate regimes,” he told Dabiq magazine.

“As a result, I would keep myself up to date on all the latest news around the Muslim world and the jihad fronts.”

Jamaat's enduring influence

Shane Crawford is among more than 100 men, women and children believed to have left Trinidad and Tobago for Syria. In excess of 30 are believed to be foreign fighters while the rest are their families.

It is unclear how many nationals from the country are actually fighting for IS. Yet, with the militants losing territory by the day, authorities have been scrambling to beef up security in case the fighters try to head back home.

Like Shane Crawford, most believed to have left have been young, black "reverts" to Islam, with about 70 to 90 percent fitting this profile.

Its sway is such that al-Rawi, Trinidad and Tobago’s attorney general, told MEE that “the jihad cause is romanticised by persons leaning towards Islam of the type seen in the 1990 [coup attempt]”.

Griffith, the former minister of national security, also said that today’s foreign fighters shared “the same ideological vein” as those who took part in the 1990 coup. MEE was also told that Shane Crawford occasionally frequented the Jamaat’s mosque.

One day during the Islamic festival of Eid al-Adha in September, I visited the Jamaat al-Muslimeen to understand whether the philosophy of this influential group of black Muslims has had any bearing on people wanting to leave for Syria.

Despite the rain, there was a celebratory mood inside the group’s vast concrete compound, which lies in the district of St James on the western edge of Port of Spain.

Children dressed in striped polo tops trod playfully in the waterlogged grass; women in colourful hijabs gathered in large clusters and gently lifted their long abayas as they stepped through puddles; young men fanned the flames of the numerous mini barbecues causing pungent black smoke to fill the air. Almost without exception, everyone was black.

I was led to Fuad Abu Bakr, a tall, lithe man who has been leading this year’s ritual sacrifice, as per Islamic tradition. He quickly greeted me before returning to chopping a fresh bull carcass in a blood-soaked white T-shirt.

Waiting nearby were three forlorn sheep tethered to a metal grilled fence; they looked on while their executioners wielded the tools that would soon bring about their demise.

I spoke to a young man who lives in the area and said he only recently started to practise the faith. “I was running around drinking and carrying on,” he told MEE before praising the Jamaat.

'Who are you really killing?'

When I finally got to speak to Fuad he was kneeling in the mosque - an airy hexagonal concrete structure - explaining the faith to four young black men. No sooner had they uttered the few words that make up the Muslim testimony of faith or shahadah than they left. They were now Muslims.

Fuad, the son of 1990 coup leader Yasin Abu Bakr, runs the youth wing of the movement. He told MEE that people were going to Syria and Iraq “to go and fight and defend their Muslim brothers”.

He doesn’t think that IS poses a threat to the country and thinks that people should be free to go. “I believe in people having choice,” he said.

He denied that the Jamaat were responsible for encouraging people to leave, but he said he was aware of a few people who had journeyed to the Middle East. When I pressed him on whether they were members of the Jamaat, he said that the group did not have a membership and that the ones he knew of had not attended regularly.

“Most of them who have left, we don’t know that they had left until after,” he said calmly. “They don't want anyone to discourage them or inform on them.”

The 31-year-old talked to me from his cool air-conditioned office. He was thoughtful and calm, his voice did not rise except for the intonation of his distinctly Trinidadian accent.

The taking of innocent lives is wrong, no matter who does it. It doesn't matter if the Russian state does it, the American state does it, or if Islamic State does it

- Fuad Abu Bakr

At the far end was a large desk with a globe next to it. And in a corner of the room stood a wooden bookshelf whose top shelf was stacked full of tomes of Islamic scripture. Below them were textbooks on maths, social studies and design, offering perhaps an indication of the Jamaat’s socio-political-religious philosophy.

While Fuad was reluctant to criticise IS, he did not condone the group either.

“The taking of innocent lives is wrong, no matter who does it. It doesn't matter if the Russian state does it, the American state does it, or if Islamic State does it," he said, before adding: “If there is justice and fairness and equality and the reduction of poverty then there wouldn't even be this type of violence in the world.”

The Jamaat rose out of the ashes of the Black Power Revolution, a period of black militancy and consciousness that began in America and reached Trinidad by 1970. The rousing rhetoric of the Nation of Islam’s Louis Farrakhan and Elijah Muhammad were to profoundly influence Yasin Abu Bakr, the Jamaat’s founder.

'Justice, change and democracy'

According to Selwyn Ryan, an Emeritus Professor of Government at the University of the West Indies, who has written a book on the coup, Abu Bakr saw himself as a “successor to the Black Power movement” who “set out to rally blacks as well as Muslims”. Though the Jamaat, unlike the Nation of Islam, are seen as orthodox Muslims, they are similarly critical of western foreign policy.

The Jamaat has always had a complicated relationship with the government. The group claims to have been given the land to build its sprawling compound - which includes two schools and a restaurant - in the 1980s by the then ruling political party.

But when an opposition party came into power, they were threatened with eviction from what had by then become a prime piece of real estate. This sense of injury, coupled with the government’s failure to tackle poverty in black communities amid a failing economy, helped to precipitate the coup.

Yet the Jamaat has since been courted by successive governments for electoral gain and even political mediation. Fuad said bluntly: “We live in a very authoritarian system. They take on the role of colonialists and they have this kind of attitude where you have to beg them for your rights.”

Fuad was just five years old when the coup took place. We moved to the window where he points to the spot his house once stood before it was razed by the army in the aftermath.

Yet children of the coup have made notable contributions to the country. Among Fuad’s siblings is a curator of the national museum, a national footballer and four doctors and dentists. He added that he himself studied law and business at Kingston University in the UK, while noting that revered Trinidadian singer Muhammad Muwakil also grew up on the compound.

I wanted to know whether the coup was an attempt to impose an Islamic state on the country and whether it could have acted as an inspiration for the likes of Shane Crawford and other fighters.

Fuad said that he retained “pride for the actions” of his father but denied that the Jamaat was attempting to bring about an Islamic state. He described his father as a “nationalist” and pointed out that he had called for elections to take place in 30 days’ time.“Justice, change and democracy, which are present in Islam, drove the coup,” he said.

He added that the Jamaat had regularly engaged in the political process through lobbying and protest, while he had founded his own party, the New National Vision, which competed in the last general election but has yet to win any seats.

Shane Crawford also poured scorn on the Jamaat for not seeking to turn the country into an Islamic state. He was quoted by Dabiq as saying: “There was a faction of Muslims in Trinidad that was known for ‘militancy’. Its members attempted to overthrow the disbelieving government but quickly surrendered, apostatised, and participated in the religion of democracy.”

'One door for blacks, another for East Indians'

Umar Abdullah recalled that on the day of the coup, he was arrested by police who found a detailed map of Port of Spain, contact details of leading politicians and an outdoor survival kit in his rucksack. After three days of sleep deprivation, beatings and little food, he was released, and he left the Jamaat soon afterwards.

But, he explained, “the coup gave young black people a voice and a sense of strength and hope”, which had led more of them to embrace Islam.

Many young black men who had converted were “inexperienced young brothers who didn’t have proper jobs” and who sometimes were drawn to petty crime.

“The brothers were part of the mosques, but they felt that the mosques weren’t tending to their needs - issues such as [dealing with] family members after conversion,” Abdullah said.

'East Indians shun African Muslims. If a daughter falls in love with an African man this is certainly not allowed'

- Umar Abdullah

Many black families, who are overwhelmingly Christian, saw Islam as an “Indian religion”, he said, and family disputes often followed conversions. “They couldn’t pray at home,” he added.

Umar Abdullah, who is an East Indian, said that racism had also played a part in a feeling of disenfranchisement among black Muslims. Though things were improving, it remained commonplace for “East Indians to shun African Muslims. If a daughter falls in love with an African man this is certainly not allowed”.

While living in Tobago, he recalled, the mosques there had “one door for blacks and another for East Indians”.

These differences appear to go to the top of the Muslim community, according to Abdullah. Mosque committees are dominated by East Indians and so are “not representative”, while the Jamaat and another mosque in Rio Claro, also popular with black Muslims, “are left out of discussions with other Muslim organisations”.

Abdullah believed that these factors may have been an influencing factor on young men such as Crawford.

“When they feel they have no hope they will go elsewhere and they will have a purpose,” he said ruefully.

ASJA, the largest umbrella organisation for Muslims in Trinidad and Tobago, declined on a number of occasions to answer MEE's questions.

The 'dying gasp of black youth'

Professor Andy Knight, an academic who had conducted research into home-grown violent extremism in Trinidad and Tobago, said that many of those who had left for Syria and Iraq “feel marginalised from the society”.

“Some of them have been engaged in criminal activity on the island. Some have spent a long time in remand. The justice system in Trinidad and Tobago is woefully inadequate,” he said.

Their bleak image of black Muslims in Trinidad and Tobago is even more harrowing when seen against the backdrop of troubles affecting the wider black community.

According to Professor Ryan, who is also an influential newspaper commentator, institutional racism and government policy based on identity politics have left blacks in a dire state.

“In the past, blacks controlled the bureaucracy and government, Indians controlled commerce - that has now gone,” he said.

His research shows that whereas 37.5 percent of businesses were black-owned in 1992, this figure had shrunk to 30 percent by 2000. Social factors also play their part: more than 50 percent of Afro-Trinis grow up in single parent families, according to a report submitted to the United Nations Development Programme in 2013.

Ryan, who spoke to MEE in his hilltop house with a view of Venezuela across a yacht-filled sea, shook his head and said plaintively that if this situation is not reversed it could well be “the last dying gasp of black youth”.

For now however, Attorney General Al-Rawi sees a more pressing challenge in strengthening his country’s counter-terrorism capacity to address the potential threat posed by those returning from Syria or those who might fall under their influence.

A new counter-terrorism strategy would include regular meetings with mosques and being “upfront with the media”, he explained.

“We are talking to foreign jurisdictions to bring in a little bit more specialist counter-terrorism management which will ultimately be targeted at the khutbah - the sermon that comes from the mosque,” he said.

“This is something that is not reinvention of the wheel, what we’re doing is what the rest of the world is doing,” he added.

'Open and honest dialogue' with returnees

But Andy Knight said that the government needed to be careful, while weeding out those who posed a genuine threat, not to “paint all Muslims with the same brush”.

Citing concerns with the UK Prevent counter-extremism strategy, which he described as “folly”, and the US countering violent extremism strategy, Knight is currently working on a new counter-terrorism model for Canada that he said was “based on reducing the chance of picking on a specific ethnic or religious group”.

“The focus ought to be countering violent extremism of all sorts, whether they are from gangs, the police, white supremacists, or homegrown terrorists,” he said.

One such initiative, begun in Trinidad and Tobago in 2007, is the Citizenship Security Programme (CST). It is a collaboration between the government, grassroots community groups and religious organisations which organises sporting events, cultural activities and educational workshops in high-crime areas across the country.

The programme has been praised by the United Nations Development Programme, but was recently axed by the government despite the country's soaring murder rate.

Umar Abdullah, who spearheaded a branch of the programme in Tobago, thinks a version of the programme is needed now more than ever given the number of people who have left for Syria.

Abdullah showed MEE a proposal he had submitted to the Ministry of National Security, which builds on the Citizen Security Programme that he says is now being considered by the government.

“It is very important to have an open and honest dialogue with returnees. If there is reason to believe a person has committed a crime, authorities must be clear that they will do everything in their power to prosecute. Yet if an individual has not committed a crime or it cannot be proven, they should do everything possible to reintegrate the person,” he said.

"Both of these legs are critical. The bottom line, however, is that all young people want a happy life - they want to reach the goals they set, such as building a family. For a government, the most important task is to create the framework and conditions that make these opportunities possible for all citizens.”

- Amandla Thomas-Johnson is a freelance journalist who was part of Channel 4's Dispatches investigative journalism programme. His work has been published in The Guardian, Buzzfeed News, Vice News, The Independent and the i newspaper.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

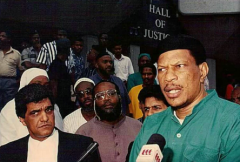

Photo: A screengrab of alleged Trinidadian IS fighters taken from an IS propaganda video

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.