How Islamophobia became a global scourge

This text is adapted from the author’s keynote address at the March 2023 Fourth International Conference on Islamophobia in Istanbul.

American and European domestic and foreign policies and politics, and the notion of a global “war on terrorism”, have played a major role in the growth of Islamophobia, both domestically and internationally. But the biggest crises of Islamophobia now exist outside of the western world, with the genocides against the Uyghurs in China and the Rohingya in Myanmar, alongside the dangerous growth of Islamophobia in India under the Modi government.

While often overlooked, the origins and roots of modern forms of Islamophobia in the West shape attitudes and government policies towards Islam and Muslims, influencing the current globalisation of Islamophobia.

While Muslims lived in western countries prior to the 1979 Iranian revolution, their numbers remained relatively small. They had no broad-based identification or visibility as Muslims. Arabs and Muslims were identified primarily by their country or ethnic background - Egyptian, Lebanese, etc - rather than by their religion, and there were few mosques in the US.

Prior to the Iranian revolution, Islam and Muslim politics were largely invisible in relevant professional organisations, such as the Middle East Studies Association and the American Academy of Religion; in the training of diplomats and the military; in education in most schools, colleges and universities (with the exception of a handful of universities); and in media.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

When I finished my PhD in 1974, there were no jobs in Islamic studies, no book contracts, no invitations to speak. This all changed dramatically with the Iranian revolution. As I have often said, I owe my career, and my first Lexus, to the Iranian revolution.

Iran’s Islamic revolution, and the resurgence of Islam in Muslim politics, society and culture, was totally unexpected. Ayatollah Khomeini’s call for the export of its Islamic revolution became the lens through which western governments and many of their citizens, who knew nothing else about Islam, now encountered Islam and Muslims.

Fear of what came to be called “Islamic fundamentalism”, or the “Green Menace”, heavily covered in the news, was reinforced by subsequent hijackings, hostage-takings and other acts of terrorism.

Clash of civilisations

Long before Samuel Huntington’s warnings of a “Clash of Civilizations”, one prescient scholar, Edward Said, warned in 1981, in the aftermath of the Iranian revolution, of what was to come.

He warned: “For the general public in America and Europe today, Islam is ‘news’ of a particularly unpleasant sort. The media, the government, the geopolitical strategists, and - although they are marginal to the culture at large - the academic experts on Islam are all in concert: Islam is a threat to western civilisation.”

Negative images of Islam were prevalent, corresponding not to what it was, but to what prominent sectors of a particular society took it to be, he added: “Those sectors have the power and the will to propagate that particular image of Islam, and this image therefore becomes more prevalent, more present, than all others.”

The 9/11 attacks in the US and subsequent attacks in Europe … led to an exponential increase in global Islamophobia

More than 10 years later, in a 1993 Foreign Affairs piece titled “The Clash of Civilizations?”, Samuel Huntington argued that after the Cold War, conflicts over cultural and religious identity would dominate global politics.

Statements by western policymakers and media commentators increasingly warned of an “Islamic threat”. It was a triple threat to the West: political, civilisational and demographic, feeding a notion of an impending clash of civilisations.

Around the time of the Islamic Salvation Front’s electoral success in Algeria in 1991, I met with the US assistant secretary of state. He asked whether Algeria would be another Iran; I explained the differences between the two countries. At one point, he noted that with the defeat and withdrawal of the Soviet Union from Afghanistan, Islam and the many Muslim countries were the only significant global ideological political presence and power.

9/11 and the 'war on terrorism'

In recent years, the major catalysts in the exponential growth of Islamophobia in the US and Europe have included the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon by al-Qaeda, and subsequent attacks in Europe; the successful spread of the Islamic State group in Iraq and Syria; and mass immigration to the West, fuelling the rise of the far right and white nationalism, which have affected American and European politics.

The 9/11 attacks in the US and subsequent attacks in Europe, including the 7/7 bombings in London, led to an exponential increase in global Islamophobia - and with it, a fear of Islam and Muslims in popular culture.

Islam and Muslims - not just Muslim extremists and terrorists - were cast, and in many cases demonised, as the radical “Other” in western media and society. The US-driven global “war on terrorism”, with all its rhetoric, policies and actions - including the invasion and occupation of Iraq and Afghanistan, the US Patriot Act and Guantanamo Bay - would ultimately lead to the globalisation of Islamophobia.

This phenomenon spread far beyond the borders of the West to the Muslim world, as well as non-Muslim Asian countries, such as India, Myanmar and China. Its victims were not just a small minority of Muslim extremists and terrorists, but also, and more broadly, the faith and identity of the mainstream majority of Muslims.

Mass media, and especially social media, have played a critical role in the spread of Islamophobia, providing a platform for anti-Islam and anti-Muslim statements by political and religious leaders, media commentators, and a host of other “preachers of hate”. As the old adage goes, “if it bleeds, it leads”; in other words, sensational bad news increases readership and sales.

A 2011 report by Media Tenor, titled “A New Era for Arab-Western Relations”, found that out of nearly 975,000 news stories from American and European media outlets, networks significantly reduced coverage on events in the Middle East and North Africa region to the actions of Muslim militants.

A comparison of media coverage in 2001 versus 2011 demonstrated a shocking disparity: In 2001, two percent of all news stories in western media presented images of Muslim militants, while just over 0.1 percent presented stories of ordinary Muslims. In 2011, 25 percent of stories presented the militant image, while images of ordinary Muslims hardly increased, at 0.5 percent.

The result was an astonishing imbalance of coverage: a significant increase in media coverage of militants, yet no increase in coverage of ordinary Muslims over the same 10-year period.

Explosion of social media

This was accompanied by an explosion of social media websites, with domestic and international impacts and consequences. Users took advantage of bad news to spread prejudice and hate, painting all Muslims with the terrorist brush. An organised Islamophobia network emerged, with social-media campaigns relying on a cottage industry of pundits, bloggers, authors, lobbyists, politicians, and ideological, agenda-driven anti-Muslim polemicists with significant funding.

In response to the 16 October 2020 brutal murder of a secondary school teacher by an 18-year-old Chechen immigrant, the French interior minister called for swift measures against “the enemy within”, a reference to France’s Muslim community. Their religion and culture were seen as a threat.

Under the banner of protecting the state from “Islamic terrorism”, French authorities launched a crackdown not just on extremists and terrorists, but also on the country’s six million Muslims.

The government carried out raids targeting Muslim civil society, marking 231 people for deportation, arresting dozens of others, and classifying more than 50 Muslim associations for potential dissolution. Many French Muslims feared the government was weaponising the killing to institute a government policy equating Islam with terrorism.

One of the organisations French authorities identified for dissolution was the Collective Against Islamophobia in France, an advocacy organisation that documents hate crimes against Muslims. The group had cited rising anti-Muslim sentiment in France and found that in 2019, there were nearly 800 anti-Muslim acts, a 77 percent increase in two years.

Yet, French Interior Minister Gerald Darmanin, with no proof, called the organisation “an enemy of the republic”. The government shut down at least 73 mosques and Islamic schools in 2020. President Emmanuel Macron, like right-wing candidates Marine Le Pen and Eric Zemmour, campaigned for an “Islamist separatism” law, saying government measures were needed to fight “political Islam”.

Criminalising political Islam

Similar to Macron’s crackdown on Muslim civil society, in the early morning of 9 November 2020, Austrian forces raided the houses of around 70 Muslim community leaders and academics across the country on suspicion of organising terrorism and money laundering. Involving more than 900 police officers, special agents and other officials, Operation Luxor, named after an ancient city in Egypt, was the largest coordinated police raid in Austria since the Second World War.

Farid Hafez, an Austrian scholar, expert on Islamophobia and senior researcher for Georgetown University’s Bridge Initiative, and his family were among the victims.

Chancellor Sebastian Kurz then announced on 11 November 2020 a proposed law to make “political Islam” a criminal offence. Austrian authorities said the raid targeted people with alleged links to the Muslim Brotherhood and Hamas. Despite this allegation, not a single person was charged.

The Chinese government has further entrenched Islamophobia by spreading false information about its treatment of Uyghurs

In addition to the trauma of the raid, those arrested had their assets and bank accounts frozen, affecting their ability to pay rent and legal fees.

According to Helmut Krieger, a political scientist at the University of Vienna, Operation Luxor “was intended as a means to criminalise the politically active Muslims in Austria under the label of political Islam. How the Austrian state understands political Islam is deeply influenced by the understanding of it by Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Israel.”

Yet, perhaps no state is as organised and systematic in its oppression of Muslims on the basis of their ethnicity and faith than China. It has imprisoned Uyghurs in what some would call concentration camps, alongside increased and enhanced surveillance of their homes, mosques and daily life. The state has also used social media in an attempt to combat reports of Uyghur abuse.

In response to being accused of genocide, the state strategically launched a disinformation campaign. Hiring social media influencers and content creators, the Chinese government has further entrenched Islamophobia by spreading false information about its treatment of Uyghurs. The greatest tool at China’s disposal in this information war is its ownership of the rapidly growing and incredibly popular app, TikTok.

Dispossessing Muslims

The situation in Myanmar most closely resembles that of China. Where China targets Uyghurs, a predominantly Muslim ethnic group, the political elite in Myanmar targets the Muslim ethnic Rohingya.

Similar to India, where state representatives rely on the support of Hindu religious extremists, security forces in Myanmar depend on the support of Buddhists led by extremist monks.

The most obvious manifestation of Islamophobia in Myanmar has been the systemic genocide of the Rohingya. In recent years, the torture of Rohingya Muslims has been thoroughly documented and reported by major human rights groups and the media.

Much as in India, government repression includes dispossessing Muslims from their own lands, and legally recognising the “property ownership” of settlers who have claimed Rohingya homes.

In India, Islamophobia is arguably rapidly approaching a climax in the country’s 75-year history. Startling examples of Islamophobia can be found in legislative, educational, professional and private spaces.

Many Muslims are finding classrooms to be hostile spaces. In one instance, a professor alleged referred to his Muslim student as a terrorist. Muslim women have also been banned from wearing the hijab on school property.

Unfortunately, it is not only the classroom where Muslim women are unsafe in India. Shocking the global community, in August 2022, the state freed 11 men convicted of gang-raping a Muslim woman in 2002 on the basis of her faith. Their release was further evidence of the Modi government’s increasingly anti-Muslim orientation and policies.

State-sanctioned violence and repression includes bulldozing properties owned by Muslims. In a move strikingly similar to Israeli army policies, Muslims have reported arriving home to find Indian state officials with papers permitting them to destroy their homes or property.

The Modi government has used the term “love jihad” as an excuse to surveil Muslim men and promote Islamophobic narratives about them, with men accused of trying to increase their numbers by tempting Hindu women away from Hindu men.

Finally, many Muslims in India report facing intense discrimination when seeking employment, alongside a rise in explicitly anti-Muslim music featuring hateful lyrics. And on social media, as journalist Alishan Jafri recently noted, for many young Indian Muslims, their feeds have begun “looking like a visitors’ diary outside a busy graveyard”.

Authoritarian regimes

At the same time, governments and regimes in many Muslim countries - such as Egypt, Syria, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Algeria and Tunisia - have practiced their own brand of Islamophobia. They have stoked fears of a global Islamic threat at home and abroad.

Authoritarian rulers across the region have consistently and deliberately failed to distinguish between terrorist groups and mainstream Islamic organisations, political parties, social welfare agencies and human rights groups.

Egypt legitimised its military coup, slaughter, imprisonment and torture of tens of thousands of members or supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood, along with mass trials and death sentences, on the grounds that they were Muslim terrorists.

President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has used his appointed religious leaders and their institutions to advocate an “Islamic reformation” to review and presumably discard centuries-old Islamic traditions, as evidence of Sisi’s own anti-Islamist credentials.

The UAE and Saudi Arabia, major supporters of the coup that deposed Egypt’s democratically elected president, subscribe to the same mantra. All three cite in particular the Muslim Brotherhood, openly warning western governments about a global threat from the Brotherhood not only in the Muslim world, but also in the West, aiming to immunise themselves from criticism for their own human rights records.

“Arab regimes spend millions of dollars on think tanks, academic institutions, and lobbying firms in part to shape the thinking in western capitals about domestic political activists opposed to their rule, many of whom happen to be religious,” noted Ola Salem and Hassan Hassan in a 2019 Foreign Policy article.

Arabs as the 'enemy'

Islamophobia in Israel/Palestine is one of the least-covered examples. Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) has succinctly underscored its importance in Israeli politics, and its devastating impact on portraying Muslims and Arabs as the “enemy” and denying their fundamental rights.

Here is an important and relevant excerpt from a fact sheet produced by JVP: “Islamophobia plays a key role in building and sustaining public and U.S. government backing for Israel. Right-wing Christian and Jewish groups dedicated to denying the fundamental rights of Palestinians deliberately fuel fear of Muslims and Arabs (commonly assumed to be Muslims) to push their agenda in the Middle East. Unwavering support of Israeli policies contributes to the characterisation of Muslims and all Arabs as the ‘enemy’ and to the perpetuation of Islamophobia, or the failure to speak out against it.

Rather than focusing on wealth and competition, leaders need to foster a deep sense of our political and religious pluralism and interdependency

“A money-Islamophobia-Israel network - bound by ideology, money, and overlapping institutional affiliations - both furthers a rabidly anti-Muslim climate in this country and helps bolster the state-sponsored Islamophobic and anti-Palestinian policies adopted and promoted by the U.S. government …

"An impetus for the view that Muslims are enemies of Israel and ‘the West’ came from the introduction in 1990 and the subsequent popularization of the term ‘clash of civilizations’: the idea that ‘Western civilization’ is locked in an implacable battle with Islam resulting from fundamental cultural differences, not history, politics, imperialism, neocolonialism, struggles over natural resources, or other factors.

“The virulently anti-Muslim 'clash of civilizations' concept views more than a billion Muslims as belonging to a monolithic, insular, inherently backward, violent, and inferior culture that cannot be changed. It provides an ideological foundation for both the ‘war on terror’ and the militantly pro-Israel belief that ‘the West’ must back Israel, because of ‘fear of large Muslim minorities - unassimilated and unassimilable’.

A new narrative

Despite their rhetorical commitments to democracy and human rights, the US and EU have consistently sided with authoritarian regimes. What former US President George W Bush called “democratic exceptionalism” was ironically used to justify the invasion and occupation of Iraq, all in the name of bringing democracy to Iraq and the Arab world, while also supporting the status quo of authoritarian allies.

They have vacillated between using “democracy” as a political and diplomatic tool against some Arab powers, and using regional violence, terrorism and instability as a justification for deeper relations with authoritarian regimes, such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain.

In Egypt, the US and EU equivocated and ultimately accepted the military coup that deposed the first democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi, and more recently, the coup in Tunisia.

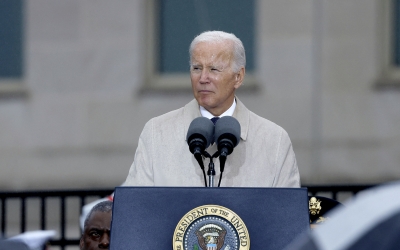

The US, Europe and the international community must not only construct a new narrative that emphasises self-determination, government accountability, rule of law and human rights, upon which political actions and policies are based - but they must also act on that narrative. This is something that no administration, including the Biden government in the US, has been willing to do.

This reinforces anti-westernism and the mantra of militant extremists that neither Arab regimes nor their western allies will “allow” democratisation - and this mantra can fuel radicalisation and recruitment by terrorist organisations.

Today, we live in a globally interconnected world through the internet, travel, global corporations and various religions. Christians, Muslims, Jews, Hindus and Buddhists are not only “over there” in foreign countries, but also right here in the West.

This interconnected world, illustrated by the Covid-19 crisis, demonstrates our 21st-century reality. If some of us are not okay, all of us are not okay. Human rights are not just about “us”, but about global rights for all.

We should move in our thinking and behaviour beyond simply considering “my” religion, “my” ethnic group or “my” country, to fostering a deep awareness of our shared planet and interdependency. Rather than focusing on wealth and competition, leaders need to foster a deep sense of our political and religious pluralism and interdependency, and lead us to work towards wider goals, encompassing our planet’s common good. Among our seven billion beings, we all have a role to play.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.