Turkey's lira: The story of an epic downfall

A decade ago, the Turkish economy was hailed as a success story all around the world, as investors flocked in with cash and direct investments and the Anatolian Tigers spurred annual growth to double digits.

It was a high time for world liquidity, as the European Central Bank and US Federal Reserve had been pumping money into the markets to alleviate the reeling impacts of the 2008 financial crisis.

Meanwhile the lira was largely stable, and Turkish citizens' purchasing power grew as income per capita crossed the $10,000 per annum threshold.

Fast forward 10 years to November 2020, and the lira is repeatedly recording new lows against the US dollar. Turkey's currency lost 30 percent of its value this year alone, with the assistance of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Some economists calculate the actual unemployment rate at 25 percent, while net central bank foreign reserves are estimated at minus $50bn.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

It is a head-scratching picture for President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who two weeks ago, after deliberations with his closest aides, swung the axe in an attempt to reverse the economy's fortunes.

First came the sacking of Central Bank Governor Murat Uysal, who had only done his administration's bidding. And then Erdogan saw to the removal of his son-in-law, Berat Albayrak, as finance minister, who had been prompted to tender his resignation.

Observers in Ankara believe Erdogan, who has surrounded himself with “yes” men in recent years, finally got the wake-up call he needed during a brief and unexpected incident in the last week of October.

While visiting the city of Malatya, Erdogan was approached by a man who calmly laid out struggles that millions of Turkey's citizens were experiencing - struggles that the president had apparently been shielded from hearing about.

“We are unemployed,” the man said. “We cannot bring bread to our homes.”

A stunned Erdogan tried to soothe the conversation by offering tea, and advising the man that he should stop exaggerating the situation.

However, people close to the president told Middle East Eye that it gave Erdogan food for thought, especially after hearing similar complaints from other parties.

He then ordered Naci Agbal, his budget director at the presidency, to prepare a report on the economic situation. Several sources suggest Erdogan lost his trust in the economic management once he learned from Agbal that the Central Bank reserves had already been depleted to support the struggling lira.

For analysts, former Central Bank officials and economists, the sad story of the depreciating lira is essentially about two major issues: erosion of the Central Bank's independence, and loss of trust in political leadership.

And both of them are problems of Erdogan’s own making.

Backdoor method

The story goes back to 2012, when then-governor of the Central Bank Erdem Basci started to utilise something called an “interest rate corridor”, the creation of multiple interest rates.

It was a backdoor method to satisfy Erdogan’s opposition to interest rate hikes, while doing what the market asked for.

“Things began to go wrong with his move towards unorthodox monetary policy,” Timothy Ash, a longtime foreign investor in Turkey, told MEE.

“There was some logic with it initially, to have multiple interest rates to stop over-appropriation of the lira due to hot money flows driven by quantitative easing post the global financial crisis. But he kept the policy too long.”

Basci’s decision to outsmart Erdogan's obstinacy has a backstory.

'Things began to go wrong with Erdogan's move towards unorthodox monetary policy'

- Timothy Ash, foreign investor

The banker and other senior officials had been trying to convince Erdogan with well-prepared graphs that he was wrong over his unorthodox theory that alleges higher interest rates lead to higher inflation.

No matter the time and the efforts put in, then-prime minister Erdogan wouldn’t budge.

Many believe Erdogan’s opposition to higher interest rates comes from his religious beliefs as a pious Muslim. But others point out that as a businessman he thinks that lower interest rates would lead to more growth and employment.

“His belief, it is straight out of 19th-century outdated economy books,” Ibrahim Turhan, a former deputy governor of the Central Bank, told MEE. “And it goes back to his years with the Nationalist Vision movement led by the former prime minister, Necmettin Erbakan.”

Erdogan began his political career under Erbakan's leadership and reached nationwide fame during his time as mayor of Istanbul under the prime minister's Welfare Party.

Erbakan had been a controversial figure for his ideas inspired by Islam, in which he defended a religious vision that could be adopted by the state and society, called “Fair economic and political order”.

A book with the same name released by Erbakan in 1991 clearly illustrates the belief that interest rates create inflation by forcing businesses to increase the prices to pay for loans they have taken out.

For a while, Erdogan’s opposition to orthodox monetary policies had been counterbalanced by several high-ranking officials, such as the much-regarded economic lieutenants Ali Babacan, who led the economy from 2003 to 2015, and Mehmet Simsek, who was first sidelined and then sacked in 2018.

As Erdogan increased his confidence and power as president in August 2014, he also began to table more aggressive attacks on the Central Bank for hiking the rates.

“Markets and investors still didn’t take Erdogan very seriously because they had confidence in the Central Bank,” Turhan said.

By then, $1 was still equivalent to two lira; it was still relatively stable.

That year, the US Federal Reserve and European Central Bank announced decisions to withdraw money from the markets, increasing pressure on Turkey to hike its rates.

Political risks also played their part in the turmoil: Erdogan survived a 2016 coup attempt that prompted Turkey to enter a state of emergency; while conflict with Kurdish separatists reignited and spilled over into Syria. Meanwhile, multiple bloody terror attacks were carried out on Turkish soil.

However, the main worrying signal for the markets, according to Turhan, was that from autumn 2016 the Central Bank, under its new governor, Murat Cetinkaya, was no longer able to independently make monetary decisions.

The bank started to use backdoor tactics to increase interest rates, such as predominantly funding the markets by using the late liquidity window, something that is supposed to be used as the exception rather than the rule.

“This was the first time we started to see that credit risk, known as CDS, passed over 300 points,” Turhan said. Within a few months the dollar-lira exchange rate passed 3.80.

Investor worries over economic management once again soared in March 2018, as snap elections that would introduce the new executive presidential system - granting extensive powers to the head of state - were announced. The dollar appreciated further and reached over four lira.

At this point, Turkey had been carrying a huge current account deficit over the years, and the annual deficit was expected to be over $55bn, which was supposed to be financed by the cash flows brought by investors.

Turkish banks and the private sector also had a whopping $200bn debt to be restructured.

Stunned silence

But for investors, the final blow came as Erdogan made a trip to London in May 2018 to reassure financiers of the opportunities to be found in Turkey.

Speaking to a room full of the heads of the world's largest investment funds, the president left his audience in stunned silence when he signalled that he didn't believe in the value of an independent Central Bank.

“When the people fall into difficulties because of monetary policies, who are they going to hold accountable?” he said in an interview with Bloomberg.

“They’ll hold the president accountable. Since they’ll ask the president about it, we have to give off the image of a president who’s influential on monetary policies.”

The lira that day broke another record of depreciation in the markets, reaching 4.39 to the dollar.

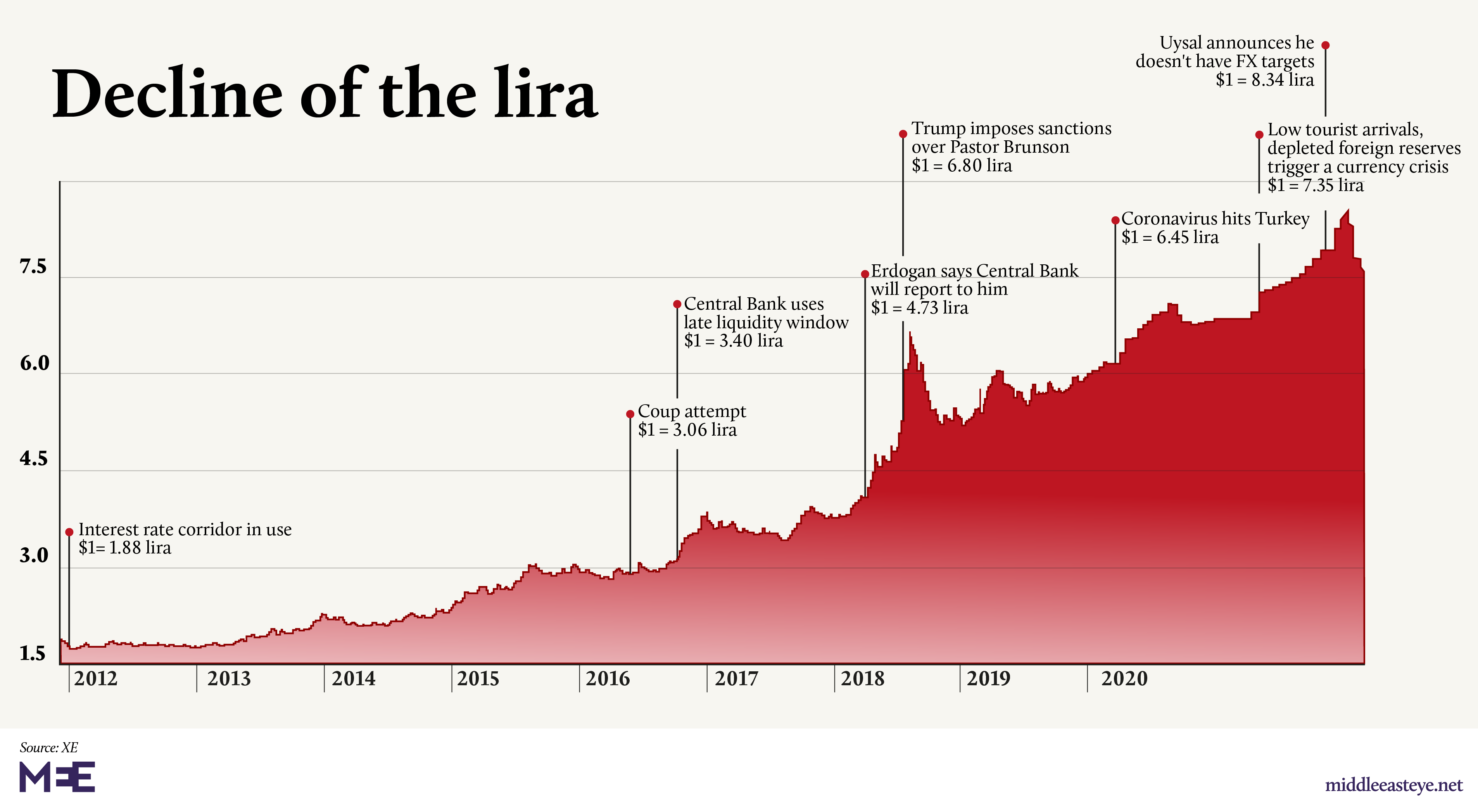

Timeline: The fall of the Turkish lira

+ Show - HideJanuary 2012 - Interest rate corridor in use, $1 = 1.88 lira

June 2013 - Gezi Park protests, $1 = 1.93 lira

December 2013 - Corruption inquiry into the government, $1 = 2.12 lira

August 2014 - Erdogan elected as president, $1 = 2.18 lira

June 2015 - Parliamentary elections, $1 = 2.66 lira

July 2015 - Clashes with PKK resume, $1 = 2.75 lira

November 2015 - Snap elections, $1 = 2.92 lira

July 2016 - Coup attempt, $1 = 3.06 lira

November 2016 - Central Bank uses late liquidity window, $1 = 3.40 lira

April 2017 - Referendum brings in executive presidential system, $1 = 3.67 lira

November 2017 - US sues Halkbank deputy chairman over Iran sanctions busting, $1 = 3.95 lira

May 2018 - Erdogan says Central Bank will report to him, $1 = 4.73 lira

August 2018 - Donald Trump imposes sanctions on Turkey over detained pastor Andrew Brunson, $1 = 6.80 lira

September 2018 - Central Bank makes a 625-point rate hike, $1 = 6.00 lira

December 2018 - Lira stabilises, $1 = 5.2 lira

May 2019 - Election body decides to renew Istanbul mayoral elections, $1 = 6.12 lira

June 2019 - Opposition wins Istanbul mayoral elections, $1 = 5.70 lira

July 2019 - Erdogan sacks Central Bank governor Murat Cetinkaya, $1 = 5.56 lira

October 2019 - Turkey begins offensive in northeastern Syria, $1 = 5.70 lira

March 2020 - Coronavirus hits Turkey, $1 = 6.45 lira

May 2020 - Watchdog fines three foreign banks for “currency manipulation”, $1 = 6.82 lira

June 2020 - The credit boom begins, $1 = 6.85 lira

August 2020 - Low tourist arrivals and depleted foreign reserves trigger a currency crisis, $1 = 7.35 lira

September 2020 - The government stops selling FX to support the lira, $1 = 7.80 lira

October 2020 - Central Bank governor Murat Uysal announces that he doesn’t have FX targets, $1 = 8.34 lira

November 2020 - Erdogan reshuffles economic team, $1 = 7.80 lira

Later, in June 2018, Erdogan used campaign speeches to promise that, with the new executive powers the presidency wields, he would show everyone “how to combat with the interest rates” if re-elected. With his subsequent victory, the exchange rate rose further to 4.70.

The plummeting lira didn't seem to be of immediate concern to Erdogan, however, who took the expected but far from orthodox move of appointing his son-in-law Albayrak to the finance and treasury ministry.

The markets perceived the move as another signal that qualified technocrats such as Mehmet Simsek would be out and monetary and finance policy from now on would be as politicised as Erdogan publicly declared in May.

Erdogan had a special liking for Albayrak, who holds an MBA from New York Pace University and led the construction and energy conglomerate Calik for years as its CEO.

Albayrak wasn’t a mere son-in-law, but someone Erdogan trusted completely as a confidant on sensitive topics such as an oil deal with the Iraqi Kurdistan Regional Government, which was kept under wraps for years before Albayrak became a minister.

Albayrak’s western-educated outlook and his success as an energy minister had further solidified the president’s confidence in him. After many political betrayals and a coup attempt, Erdogan more and more began to reduce his circle of trust to his family.

Albayrak, on the other hand, had been given a specific but almost impossible task: finding a way to keep interest rates low while maintaining control of the lira.

But the new finance minister never stood a chance once US President Donald Trump, a month into Albayrak's reign, sanctioned Turkey over the imprisonment of an American pastor, which exposed cracks in the Turkish economy.

Investors fled, and locals also flocked to the US dollar to preserve their savings. The exchange rate, which had briefly risen to 6.8 lira in mid-August, gradually decreased after Uysal convinced Erdogan and Albayrak to hike the rates by more than 6 percentage points.

Towards the end of 2018, the exchange rate was stabilised around 5.2 lira.

Speaking to MEE on condition of anonymity, a foreign investor personally credited Albayrak for delivering the rate hike and gaining some sort of trust in his fiscal policies.

However, Albayrak’s solution for a shrinking economy while inflation was soaring was pumping more credit into the markets, which was certain to weaken the lira.

“As the government made credit growths with low interest rates, the non-performing loans have begun to climb through the roof,” said Nesrin Nas, a veteran politician and economist.

“The private banks have eventually refused to do so, but Albayrak utilised public banks and later pressured private banks as well.”

According to Nas, one of the fundamental problems about Albayrak’s economic policy was keeping interest rates low to the point that they were below the annual rate of inflation, therefore effectively negative.

“Foreign investors have continued to flee whenever they found an opportunity,” Nas said.

End of autonomy

The next crisis occurred when Erdogan fired the Central Bank governor Cetinkaya in July 2019 for his resistance to cutting rates.

Albayrak hand-picked his replacement, Uysal, and effectively ended the limited autonomy the Central Bank governor had enjoyed since 2015.

“The result was that people - locals and foreigners - were simply not paid enough to hold lira, to compensate for inflation eroding the real value of lira,” Ash, the investor, said.

'The depreciation of lira has become an inevitability when [the government] didn’t permit the monetary policies that could break this circle'

- Hakan Kara, former chief economist at the Central Bank

“And we saw a mass sale of lira by locals and foreign investors. Since 2015, portfolio outflows have totalled something like $40bn, while local purchases of dollars has totalled over $120bn given dollarisation.”

Devaluation increased following Cetinkaya's sacking, and a fresh Turkish offensive in northeast Syria drew international condemnation and brief American sanctions. By January 2020, the rate was nearly six lira per dollar again.

At this point, government insiders were encouraged that the worst appeared to be behind them, as the economy recovered from the 2018 currency crisis. In order to support growth, the treasury made huge spendings and, in an unprecedented move, used the Central Bank's contingency reserves of 50bn lira for unspecified government spending.

“Whenever the economy has weakened, [the government] has tried to energise it by pumping credit [into the markets],” Hakan Kara, a former chief economist at the Central Bank, told MEE.

“However since we couldn’t have resolved the [rising] inflation problem, these credits have moved to the FX and increased the dollarisation. And Turkey entered a downward spiral with the further increase of foreign debt. The depreciation of the lira has become an inevitability when [the government] didn’t permit the monetary policies that could break this circle.”

The plans began to go south as the coronavirus pandemic hit Turkey, which shrank the economy, resulted in further unemployment and depreciated the lira because Erdogan refused to stop cutting interest rates until May.

What followed was shocking for everyone.

In order to encourage the debt-ridden and bankrupt construction sector and increase automobile sales, Albayrak in June announced one of the largest credit growths in the republic’s history with historically low interest rates.

As banks pumped more money into the markets, the exchange rate started to take off once again.

But this time Albayrak had a different plan: instead of utilising the Central Bank to buy lira from markets and stabilise the exchange rate, he began to deploy sophisticated backdoor tactics, such as burning the bank's foreign reserves through state banks to keep the dollar down. Estimates for this year alone put the quantity of reserves burned through at between $50bn to $60bn.

In order to cover his tracks, Albayrak also deployed a sophisticated swap method with local banks' foreign currency funds that made the Central Bank reserves look strong.

The whole thing started to unravel in August, as Albayrak’s bet that post-Covid recovery and tourism income would make a difference didn’t go as planned.

Tourist numbers in the summer decreased by 81 percent, and the loss of income has been calculated at more than $11bn. As new coronavirus cases in the country started to rise again, countries such as Germany and the UK tightened their restrictions for travel to Turkey.

The economic management team at one point stopped selling foreign reserves through the public banks in September because it had already run out of money. And absent a rate hike, the lira went in freefall, over and over recording new lows.

By the beginning of November, with the worries that a Joe Biden presidency in the United States would likely bring sanctions against Turkey over its purchase of Russian missile systems, the lira weakened further to 8.58 against the dollar.

'As they say, trust, like the soul, never returns once it is gone. The interest rate hikes are like an aspirin that would take the pain but wouldn’t cure the disease'

- Nesrin Nas, politician and economist

Nas, the economist, says that had the Albayrak team followed orthodox policies with sound monetary decision-making, the whole thing could have been averted. “There could have been a soft landing if the Central Bank had been independent,” she said.

Earlier this month, after the reshuffle at the top of Turkey's economic team, the Central Bank hiked the rates to 15 percent with a 475-point increase, meeting the market's expectation. Many investors saluted the move as something that could re-establish the credibility of the bank.

Nas doesn’t agree.

“As they say, trust, like the soul, never returns once it is gone,” she said. “The interest rate hikes are like an aspirin that would take the pain but wouldn’t cure the disease.”

She says in order to permanently fix the economy there are more steps that Erdogan might be too cautious to take.

“You have to repair your international relations, be transparent and establish accountability. You have to grant independence to the Central Bank and place measures to inspect the national budget. You have to make meaningful structural reforms such as fixing the public tender law and draft a strong economic plan.”

Turhan, the former Central Bank deputy governor, thinks with the new hike the lira could be stabilised until the beginning of the new year.

"Who knows, Erdogan might come back to his senses and follow a rational monetary policy," he said. "He is known for his opportunistic moves."

Illustration by Mohamad Elaasar

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.