Why Iranian Kurds have been resistant to the regional turmoil - so far

While the derailment of the Arab Spring has brought more destruction, radicalism, and civil wars to the Arab world, this same period has been one of increased salience and significance of the Kurds in regional politics.

The KRG has expanded its territory by more than 40 pecent in this period

It’s been a time of political, psychological, emotional and, to some extent, even military interconnectedness, with the fight against the Islamic State (IS) group, in particular, leading to the emergence of a Kurdish public sphere in the region.

When it comes to Kurdish political consciousness, their national project and power projections across the region, the borders that divided the Kurdish populations of the Middle East across Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria, have lost their relative significance.

In fact, the border between the Iraqi and Syrian Kurds has effectively ceased to exist.

Golden opportunities

As a result of the fight against IS, the Kurds of Iraq have gained additional territories, military equipment and new partners, and they have become more vocal in their search for independence.

Indeed, the Iraqi Kurds have more or less captured most of the lands that were designated as disputed between the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and central Iraqi government in the Iraqi constitution, drafted in 2005.

Since the onset of the Syrian crisis, the PYD first established its foothold in northeastern Syria in July 2012, and later dramatically expanded the boundaries of this enclave

In Article 140, the constitution set out the mechanisms to be used to solve these disputes, namely normalisation, censuses and referendums. In addition, Article 119 could also be used to settle these issues as it contains a provision that allows governorates to become or join an existing region through a referendum.

The resolution of these disputes was supposed to be achieved no later than 31 December 2007. But to the chagrin of the KRG leadership, the provision in Article 140 has yet to be implemented.

In practice, the Kurds have almost solved this issue as a result of their fight against IS. The more land that IS loses, the closer the Kurds get to the boundaries of their projected homeland. To be more precise, the KRG has expanded its territory by more than 40 percent in this period.

And one of the inflammatory aspects of the upcoming independence referendum, which is set for 25 September 2017, is that it will not only take place in the KRG, but also in the disputed territories as well: in Makhmour in the north, Sinjar in the northwest, Khanaq in the east and, most crucially, the oil-rich province of Kirkuk.

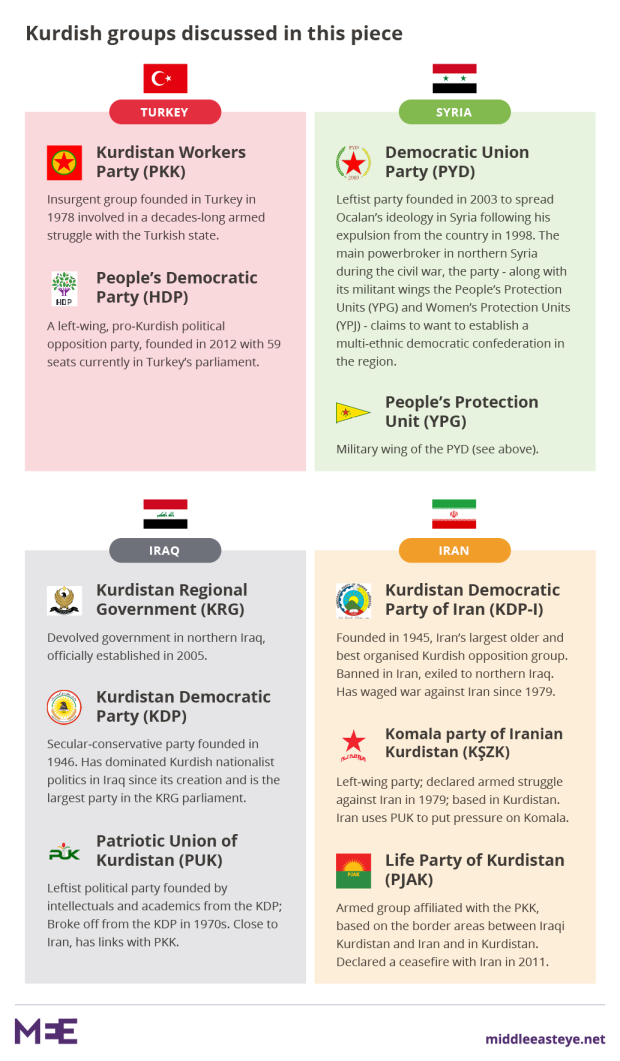

Likewise, in Syria, as a result of the fight with IS, the Kurds have transitioned from being an oppressed and marginalised group - a considerable number of Syrian Kurds were even denied a national identity card - to become one of the most potent political actors in the country, controlling a significant chunk of its territory.They have also effectively become American boots on the ground through the US’s creation of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the backbone of which is formed by the armed wing of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), the People’s Protection Units (YPG).

Since the onset of the Syrian crisis, the PYD first established its foothold in northeastern Syria in July 2012, and later dramatically expanded the boundaries of this enclave. With it has come international recognition and also legitimacy, much to the dismay of Turkey.

In a similar vein, despite the devastation caused by urban warfare between Turkey and the PKK, the Kurdish political scene has witnessed one of its most vibrant periods in recent years in Turkey.

Although it saw setbacks in the 1 November 2015 repeat election, in June 2015 the pro-Kurdish People’s Democracy Party (HDP) received the highest percentage of the vote - 13.16 percent (past the 10 percent electoral threshold to enter parliament) - in the history of civilian Kurdish politics in Turkey, which has represented a continuous tradition since 1990.

Since then, various parties that preceded the HDP were closed down for their “separatist” activities, but after each closure, a new party has been founded to take its place.

Quiet on the Iranian front

Against this picture, the relative quietism of the Iranian Kurds has proven exceptional.

Despite being the second largest Kurdish population in the Middle East after the Turkish Kurds, and despite claims that Iran executes between dozens and hundreds of Kurdish dissidents every year, Iranian Kurdish politics have seemed to be impervious to both regional upheaval and to major developments inside the country.

Of all these Kurdish groups in the four parts of historic Kurdistan, the Iranian Kurds are the only one that had the taste of statehood in the modern Middle East, albeit a short-lived one

That doesn’t, however, mean that there hasn’t been a temporary increase in tensions or clashes between the Islamic republic and different Kurdish groups.

On several occasions Kurdish groups have clashed with the Iranian state, ending a period of two decades which saw relative calm between the Kurdish groups and the state. In early 2016, the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran (KDP-I) declared the resumption of insurgency against Iran, while the left-wing Iranian Kurdish Komala party announced that six armed Iranian Kurdish groups opposed to Iran would adopt a joint military stance in March 2017.

Yet these initiatives and incidents have not sustained their momentum, nor have they morphed into anything major. Instead the Iranian Kurdish political scene has been relatively muted.

This is curious, because, of all these Kurdish groups in the four different parts of historic Kurdistan, the Iranian Kurds are the only one that had the taste of statehood in the modern Middle East, albeit a short-lived one.

The Republic of Kurdistan, with Mahabad as its capital, was declared on 22 January 1946, but lasted only around 11 months: the Iranian army entered Mahabad on 15 December 1946 and brought a quick end to the Iranian Kurdish experiment with statehood.

This experience has formed Kurdish national consciousness and remains a significant reference point for Kurdish nationalism.

In fact, Massoud Barzani, president of the KRG and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), and the man spearheading the Kurdish independence referendum, was born under the jurisdiction of the short-lived Mahabad Kurdish republic.

This has apparently had a major impact on his political consciousness: he constantly refers to his desire to die under the flag of the Kurdistan, just as he was born under it while advancing his case for Kurdish independence.

In fact, the establishment of the KDP-I in 1945 precedes the foundation of Barzani’s KDP, which is now the strongest party in Iraqi Kurdistan, by one year.

Structural foundations

So why is the Iranian Kurdish political scene relatively feeble when compared with Kurdish movements in other parts of Middle East? Understanding the structure of Iranian Kurdish politics is crucial in answering this question.

In comparison to the Kurds in Turkey, Iraq and Syria, one of the striking features of Iranian Kurdish politics is that it has been led from exile for decades. This has created some level of disconnect between the Kurdish parties and society in Iran, and reduces the parties’ influence over society.

Instead of prioritising the political aspirations of the Iranian Kurds, the party leaders have had to balance these aspirations with the concerns of their KRG host about its relations with Iran

Iranian Kurdish parties have a hard time keeping up with the sociopolitical transformations that Iranian Kurdish societies are experiencing. This, in return, limits their appeal on the Kurdish street in Iran. In fact, there is presently neither a very charismatic political figure, nor a very powerful and popular political party in Iranian Kurdistan.

Further aggravating this disconnect is the challenging position these parties, including the PKK-affiliated Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK) find themselves in while in exile largely in the KRG. Instead of prioritising the political aspirations of the Iranian Kurds, the party leaders have had to balance these aspirations with the concerns of their host about its relations with Iran.

In fact, one of the most effective ways Iran has curbed the activism of the Kurdish groups inside the country has been by its pressure on the Iranian Kurdish group’s affiliates or parent organisation outside of Iran. Iran has successfully applied this policy with both Kurdish political camps – those that have close ties with Iraqi Kurdish political parties and those that are offshoots of the PKK such as PJAK - inside Iran.

In the case of the KDP-I and the Komala, which have deep links with the KDP and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) in the KRG respectively, Iran has pursued a three-pronged approach to curtail their activism inside Iran.

First, it has relied on its considerable influence over the Iraqi government to restrain the activities of the Iranian Kurdish parties and urged it to pressure the KRG to do the same. The pro-Iranian State of Law bloc in the Iraqi parliament, which is headed by former prime minister Nouri Maliki, for example, proposed a motion in March – which has not progressed any further until now - that called on the Iraqi government either to disarm or expel Iranian Kurdish groups operating from the KRG against Iran.

Iran's carrot and stick

Secondly, Iran enjoys an intricate web of relations with the PUK, which controls areas of Iraqi Kurdistan bordering Iran. The PUK has historical and extensive relations with the Iranian Kurdish party Komala, so through using both threats and rewards with the PUK, Iran is able to apply pressure on Komala.

Thirdly, given the fact most of the leadership of these parties reside in the KRG, Iran has warned Erbil - but also the KDP - that if the Iranian Kurdish parties resort to armed conflict in Iran or even continue occasional operations, they will face grim consequences.

PJAK, which is also based in Iraqi Kurdistan and shares a base with the PKK in and around the Qandil mountains near the Iran-Iraq border, has also set its hopes for Iranian Kurdistan against the PKK’s geopolitical calculations that have led it to focus on Syria. PJAK’s aspirations come against a backdrop of increased Iranian resources, energy and manpower since the Syrian uprising in 2011 focused on defending its regime.

The PKK, sensing emerging opportunities in Syria where the group and Iranian interests seemed to converge, focused its strategy there. Iran’s drive to save the Assad regime has led it to accommodate the drive of the PYD - which Turkey considers to be affiliated with the PKK and therefore a terrorist group - to carve out an autonomous region of its own in Syria.

Iran’s drive to save the Assad regime has led it to accommodate the drive of the PYD to carve out an autonomous region of its own in Syria

As a consequence, the PKK has made attempts to tame PJAK, which declared an indefinite ceasefire in Iran towards the end of 2011. In recent months, there have been some PJAK attacks on Iran, but they have been portrayed as unintended incidents, rather than a new policy or campaign that would spell the end of the ceasefire.

So with their aspirations downgraded relative to the geopolitical ambitions of other Kurds, Iranian Kurdish parties have found themselves in a state of inactivity. This has led to organisational decay for these parties, aggravated by a lack of sufficient resources. In turn, the parties have become even less effective at shaping Kurdish society or politics in Iran.

Enter the US

Yet starting from the during the time of the siege of the Syrian Kurdish town of Kobane between September 2014 and January 2015, in which the US ultimately played the decisive role in saving the town from falling to IS, cooperative relations between the US and the PYD-affiliated Syrian Kurds have begun to emerge.

The more the US has transitioned from a regime-change agenda to one focused on fighting terrorism, and particularly IS, the stronger the ties between the two sides have grown. In other words, since 2015, the Kurds have gradually but steadily become US boots on the ground, particularly in the fight against IS.

This partnership has awarded the PYD more land, military equipment, protection, international prominence and legitimacy, and has lessened the relative reliance of the PKK-PYD on its relationship with Iran.

Now Turkey has arrived at the conclusion that the PYD is transitioning from the Iranian orbit to the US one, eliminating one of the major points of friction between Ankara and Tehran.

Second, as Turkey’s Syria policy has undergone a dramatic change, the fate of Assad has taken a back seat to concerns over border security and the emergence of a PYD-administered Kurdish region along its border, further reducing the relative importance of what has been a sticking point between them.

Both countries now perceive a major threat from Kurdish geopolitical ambitions in the region and have rejected the Iraqi Kurdish call for an independence referendum. In fact, Iran has used even harsher language over the issue than Turkey – even more threatening than the Iraqi central government.

The growing PYD–US partnership has also paved the way for an increased convergence between Turkey and Iran in opposing Kurdish geopolitical ambitions in the Middle East

For instance, Iraqi Prime Minister Abadi has acknowledged the Kurdish right to independence yet has questioned the timing of the referendum and the way that it has been conducted, particularly criticising the Kurds for going after it without approval or consent of Iraq’s central government.

And both countries are concerned about growing Kurdish power and influence in Syria, but the level of alarm in Ankara is much greater than in Tehran. Therefore, the growing PYD–US partnership has also paved the way for an increased convergence between Turkey and Iran in opposing Kurdish geopolitical ambitions in the Middle East.

But are we witnessing any developments that might reverse the course of Iranian Kurdish politics? Are the recent sporadic clashes between the Iranian military and various Kurdish groups harbingers of a new phase in Iranian Kurdish political history?

The future trajectory

The future trajectory of Iranian Kurdish politics will be dependent on three interlinked factors. Domestically, the majority of Kurds - particularly Sunnis, who represent more than three-quarters of the Kurds living in Iran - support the reformist political camp in elections.

The victory of Rouhani was cautiously well-received by this section of society. The reformist camp is still part of the regime apparatus and operates within its strict framework, therefore it is unlikely to undertake any meaningful political initiatives towards the Iranian Kurds.

Like the Baluchs, the Kurds, which are predominantly Sunni and an ethnic minority, find themselves economically deprived and politically marginalised

But it could expand the boundaries of socio-cultural rights and improve the economic conditions of the Kurdish provinces, which are amongst the poorest in Iran.

In Iran, there is a strong correlation between poverty and confessional and ethnic minorities. Like the Baluchs, the Kurds, which are predominantly Sunni and an ethnic minority, find themselves economically deprived and politically marginalised within Iran’s identity politics.

Shia Kurds are relatively better integrated into the Iranian state structure. For instance, the Shia Kurdish majority province of Kermanshah is regarded as posing a lesser security challenge than other Kurdish areas.

Despite a relatively multicultural reading among Iranian political elites who emphasise the common Aryan roots and Islamic fraternity shared with Kurds in the country, Iranian Kurds and their aspirations are largely treated as a security concern. The elite narrative, likewise, finds little resonance among Iranian Kurds anyway.

Nevertheless, if Rouhani’s government honours its pledge of improving the socio-cultural and economic well-being of the Iranian Kurds, this will partially alleviate the situation of the Kurds. But this is unlikely to be a game-changer.

Shifting alliances

If the current regional divide engendered by the recent Qatari crisis continues and deepens, this situation will present both challenges and opportunities for all the Kurds of the region, and by extension the Iranian Kurds.

Drawing on all the region’s major players, the Gulf crisis reflects post-Arab Spring realignments, the search for a new regional order and the reinstatement a new version of the authoritarian status quo.

Both Turkey and Iran have taken a clear pro-Qatari stance, while the Arab coalition has clearly targeted both countries through their list of demands: the first and second items on this 13-item list were about downgrading the level of diplomatic relations between Qatar and Iran, shutting off Turkey’s military base in Doha and halting all military cooperation between the two countries.

Turkish-Iranian opposition to Kurdish geopolitical aspirations in Iraq and Syria will motivate the Kurds to seek and build relations with the Arab Gulf countries, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE

The longer this crisis continues, the more that emerging partnerships in the region will gain salience. In this regard, the rapprochement between Turkey and Iran is likely to have a spillover effect on regional Kurdish politics.

Both countries are likely to set aside their differences to oppose Kurdish geopolitical aspirations in Iraq and Syria. This, in turn, will motivate the Kurds to seek and build relations with the Arab Gulf countries, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

In fact, Iran has accused Saudi Arabia on several occasions of being behind the military activities of the Iranian Kurds, claims which Saudi Arabia has vehemently denied. Likewise, the PYD's search for new alliances is taking place on very shaky ground.

As long as the PKK isn’t convinced of the durability of the US commitment to the PYD in Syria, it will try to strike a balance between its relations with the US and its cold peace with Iran. This will mean that the PKK’s Iranian affiliate PJAK will be conscious of not antagonising the Iranian government, and hence more careful in observing the ceasefire that has been in place since late 2011.

If the PKK and PYD believe the US is committed to its partnership with the PYD in Syria, it is then more likely that we will see the PKK adopting a more anti-Iranian posture in its regional policy

But if the reverse is the case - meaning that the PKK and PYD believe that the US is committed to its partnership with the PYD in Syria - it is then more likely that we will see the PKK adopting a more anti-Iranian posture in its regional policy. The implication of this is likely to be PJAK reactivating its political and armed activities inside Iran.

As a corollary, if the Kurds of the region believe that the US is earnestly transitioning from an IS-first to an Iran-first strategy in the Middle East, it is then likely that the PKK, along with the Iraqi Kurds and particularly the KDP, will adopt a more anti-Iranian position to burnish their pro-Western credentials.

To reflect this shift, these actors might give up on their policy of constraining their Iranian Kurdish affiliates, a move that would likely precipitate an upsurge in Iranian Kurdish political and military activism against the Iranian government.

Given the constraints of the Iranian Kurdish political forces and their disconnection from the Kurdish population inside Iran, this activism is unlikely to bear major consequences, but it may breathe new life into the push for Kurdish nationalism inside Iran all the same.

A shorter version of this piece was published by Foreign Affairs.

- Galip Dalay works as a research director at al-Sharq Forum and senior associate fellow on Turkey and Kurdish Affairs at the Al Jazeera Centre for Studies.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A view of Palangan village in Kurdistan province, about 660km southwest of Tehran, on 11 May 2011. Iranian Shia and Sunni Kurds live side by side in Palangan, although Sunni is the religion of the majority. (Reuters)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.