In pictures: The hidden lives of the Amazigh people

On his death in 1985, Algerian photographer Lazhar Mansouri left behind thousands of portraits showing the daily lives of his townspeople as the country was going through political turmoil. He would also inadvertently document the history of the last generation of women from an Amazigh Chaoui tribe, some of whom still practised an age-old tradition of facial tattooing. These were showcased earlier this year in a special exhibition of Mansouri’s work held at The Westwood Gallery in New York City, titled “Lifting the Veil: Portraits of Amazigh Women." (All photos by Lazhar Mansouri. Courtesy and copyright Westwood Gallery NYC)

The unfussy intimacy, spontaneity and relaxed familiarity in Mansouri’s photographs, which were taken with minimal equipment, is a rare documentation of one of the most difficult periods of Algerian history as the country fought for independence from France. Mansouri’s work had not been recognised internationally until the Westwood gallery obtained it for their first exhibition of his work in 2007, “Portraits of a Village: 1950-70".

Born in the city of Ain Beida in north-eastern Algeria, Mansouri opened his first studio at the back of a barbershop. Well known in the region for his artistic skills of portraiture during the early 1950s, Mansouri was commissioned by Chaoui townspeople (Amazigh people who mostly live in the east of the country) to capture the most important and most intimate moments of their lives.

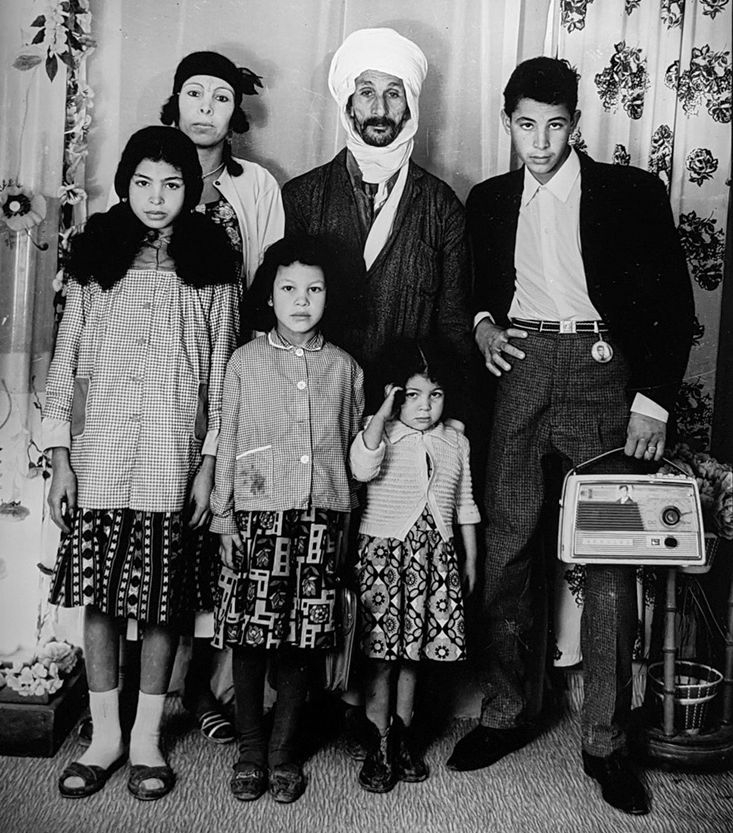

Some of Mansouri's subjects chose to be captured in relaxed poses as opposed to the more formal family portrait. Other surviving images show leather-clad teenagers posing with cigarettes, or soldiers in military relief, documenting a broad cross-section of society.

The families and individuals in Mansouri’s photographs represent a transitional phase in local culture in the period that followed the Algerian revolution (1954-1962), during the early years of independence. While some families dressed in Western clothes, others came to Mansouri’s studio in their traditional Algerian outfits and jewellery.

The women portrayed in Mansouri’s photography are of different ages and, as suggested by their clothes and jewellery, come from varying social classes. One of the features distinguishing class is the use of facial tattoos. The Amazigh facial tattoo (called Ushem or Tchiradh in local dialect) was a rite of passage to womanhood for young girls from less affluent families. Often etched to mark the onset of puberty, on the body, the face or both, this tradition, which was exclusive to women, formed an artistic social statement declaring that a girl was ready for marriage.

Amazigh women primarily turn to natural elements for inspiration in their arts - the most common tattoo, for example, is the Siyala tattoo of fertility inspired by palm trees and represented by a straight line from the lower lip to the centre or the bottom of the chin. In addition to the Siyala tattoo, many of the women in Mansouri’s photographs have a diamond shaped tattoo on their cheeks. Inspired by the shape of a star, it was also often tattooed on the cheek and believed to protect the personal safety of girls and women.

Bearing symbols of tribal belonging was also very common and was used as a visual testament of identity on the skin. But the tradition had died down in the rest of Algeria by 1962, largely due to the state’s post-independence policy of invigorating a national interest in Islamic teachings, which forbids body tattoos.

Between 1950 and 1980, Mansouri had amassed a photographic archive of thousands of images. Before he died, the 53-year-old Mansouri instructed a friend to burn the remaining archive out of concern for the privacy of his clients. But instead of burning them, the friend kept the photographs safe until the Westwood Gallery first exhibited them in 2007.

Mansouri’s photographs have today become synoptic portrayals of Algerian Amazigh culture. His work has “created dialogue and a new voice in the larger conversation of the meaning of photography and its history," say Westwood Gallery owners James Cavello and Margarite Almeida.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.