Collapsing the shelves: The challenges of publishing Arab American children's books

In my home, reading is part of our culture. I gather with my children most evenings to spend time quietly reading together, as an answer to the virtual schooling, video gaming, football watching daytime activities.

I’ve always been proud that my children love books, but four years ago, I encountered a small crisis: my daughter was frustrated.

She told me she wished she had books that featured an Arab girl as the main character. I promptly handed her Naomi Shihab Nye’s 1999 novel, Habibi, which is about a Palestinian American girl, living in St Louis, who experiences a culture shock when her father decides to move the family back to Palestine.

My daughter enjoyed seeing Arabic names and words. As a Palestinian American herself, she understood the protagonist’s mixed feelings about feeling like a stranger in Arab society. But when she asked for another book, I struggled to find one.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

As a mother, I thought back to my own Arab American childhood: hadn’t I complained about the same thing, at her age? Why had nothing changed in 30 years?

I was creating a world that should be... It was my story, right?

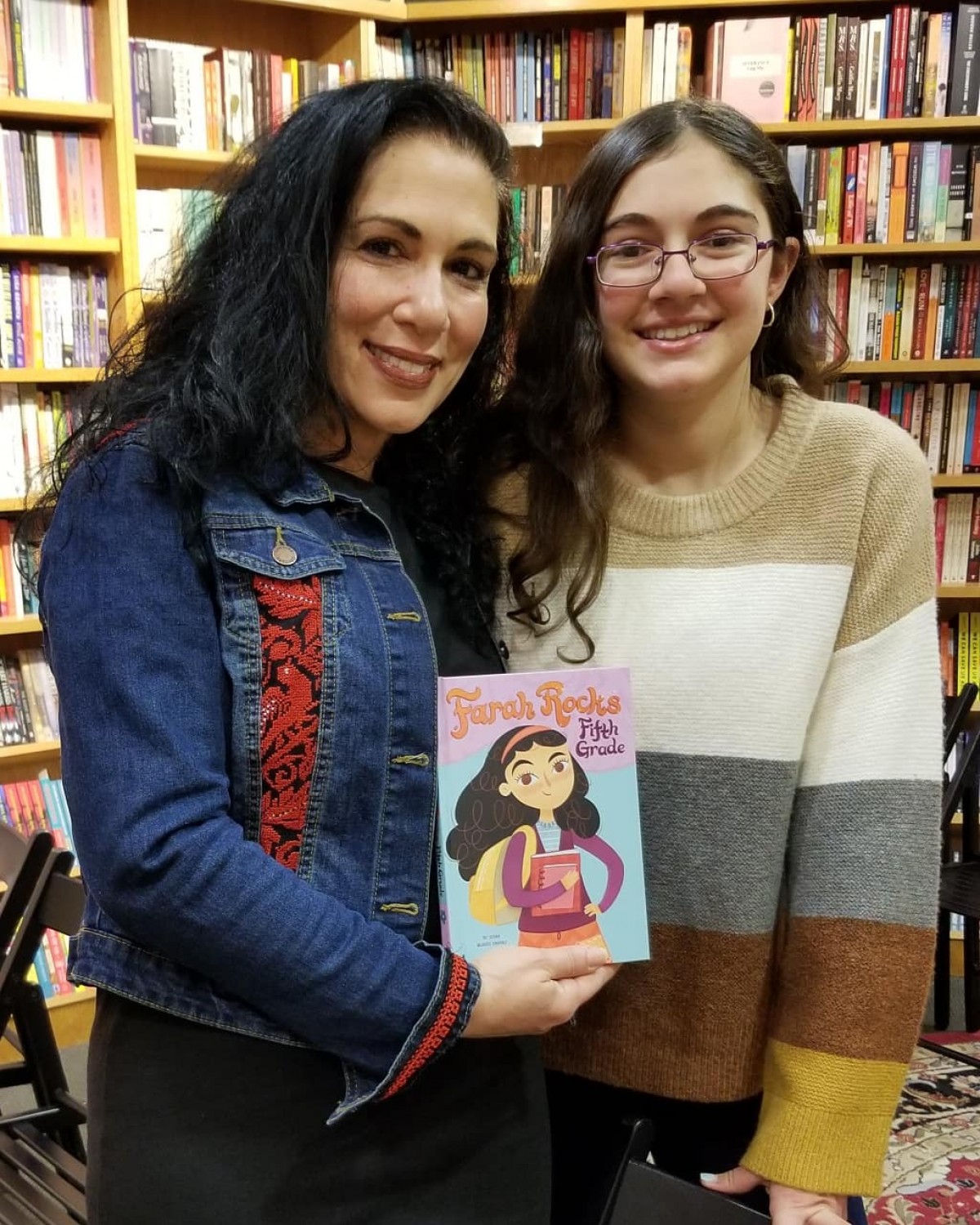

I began writing a story that very week. I invented a character named Farah, which means “joy”. This would be a joyful, happy girl, I decided.

It was my story, right? So my character would attend a school where eating hummus was as normal as wearing Nike. She would speak Arabic at home and English at school, and neither she nor her friends would find anything unusual about it.

In fact, I populated her world with other children - a Chinese-American best friend, a Puerto Rican classmate, and more - who also moved between two cultures and two languages seamlessly.

Why not? I was creating a world that should be.

Luckily, a publisher supported my vision. The acquisitions editor was actually familiar with Arab culture and literature, and she became as excited about the project as I was. Capstone signed me to a four-book deal. The third book in the series, Farah Rocks New Beginnings, was published in January.

Snack-pack culture

But the publishing industry here in the US, in all its well-intentioned attempts at inclusivity, has labelled me. It’s placed me on a metaphoric shelf, in a back corner of the bookshop.

I’m an “Arab American writer”.

That’s my shelf. (Part of a shelf, really. The stories of other brown people, including South Asians, are often housed with mine.) The industry doesn’t care that I’m also a feminist, that I grew up working class, that I love baseball, or that I am a fan of mystery novels and movies.

While America loves our food, it doesn’t seem to want to hear about our lives. Not our real lives, at least. It wants stories that it can contain in a snack-pack style container

I don’t reject the identifier “Arab American” at all. Being a person of Palestinian Arab roots in the United States has marked my life in both positive and negative ways. For example, I belong to a beautiful community, rich in its heritage and closeness.

Nothing beats an Arab hafleh or dinner party, where just as the evening is wrapping up, someone pulls out a tablah and an oud and we all start singing.

The negative aspects of being Arab American are mostly related to the stereotyping of our community, but even those are lessening. Despite living through the Trump era, my own children don’t grapple with the same problems I did at their age.

A small example: in 1985, American school cafeterias were still sites of torment for anyone with immigrant parents, and I endured years of other kids making faces as I ate my hummus out of my Tupperware.

But today’s Arab-Americans kids watch white classmates dip gluten-free, chia seed crackers and baby carrots into hummus “snack-packs”. Hummus is now a pre-packaged item that white American parents toss into their children’s lunch boxes.

It’s even manufactured in such confusing flavors - chocolate? pumpkin spice? red velvet? - that Arab Americans don’t even recognise what we’re looking at in the grocery store aisle.

There are almost four million Arab Americans in the United States, but while America loves our food, it doesn’t seem to want to hear about our lives. Not our real lives, at least. It wants stories that it can contain in a snack-pack style container – something convenient and familiar and easy to consume.

The issue, simply put, is this: The industry, which is itself homogenous, has a “chalk outline” understanding of our cultures. In its newfound zeal to acquire diverse books, it seeks stories that fit into that outline.

The chalk outline of the Arab community that exists in the minds of the industry makes it impossible for authentic stories to be published. While the children’s book industry typically leans left, its awareness of Arab culture is still informed by politics (which turns us into terrorists), and Disney (which exoticizes us).

Many editors, for example, want to acquire novels featuring young Arab American female protagonists - as long as those characters somehow “resist” or “revolt” against their patriarchal Arab or Muslim “culture”. Such stories are seen as “authentic”, based in their “sense” that Arab and Muslim communities are oppressive and patriarchal. (I’d like to know which communities aren’t oppressive and patriarchal?)

The fact remains that the most powerful image of Arab girls in the mainstream media belongs to a fictional teen in blue harem pants and a bralette, who hangs around a castle with her pet tiger.

It’s so sad, I can hardly describe it.

I teach in an MFA program, where I stress to my students that creating complex, layered characters is the hallmark of good writing. But the publishing industry doesn’t really ask this of Arab American writers. In fact, it wants to see endless replications of the outline it has dictated.

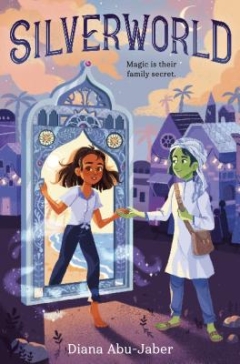

Arab American novelist Diana Abu-Jaber recently made her debut in the kidlit world with Silverworld, a beautiful and action-packed middle-grade novel about a girl on a quest to save her grandmother.

“The challenge that marginalized writers face,” Abu-Jaber told me, “is that the book industry tends to buy and promote what’s familiar, what’s popular, what they know will sell. It’s often an unconscious form of exclusion, which can make it terribly difficult to combat.”

As long as that something adheres to an already familiar outline. The industry needs to know what shelf to place you on. If only my life adhered to an outline. If only my life fit the template that the publishing industry seeks.

We need diverse books

As an Arab American writer, like other marginalised writers, if you want to exist on multiple shelves, if one shelf cannot hold all your identities, you simply don’t make it to the bestseller lists.

It’s difficult to write a novel, for example, about a girl who wants to play baseball; this girl just happens to be Arab American. I can imagine an editor considering such a pitch and asking, “What is it about her culture that prevents her from playing? Has her father forbidden it? Can we explore that?”

Children's book author, Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow, in describing the bind Black Muslim writers face, explained recently in a blog post, “It feels like we must tell incomplete stories if we want to be widely published.”

Publishers want diverse books, they say, but they don’t want the actual diversity in our lives; they want us to be one clear “thing,” something they can label.

The opportunities to be published are already so sparse. An analysis of 3,134 children’s books published in the United States in 2018, approximately 50 percent featured a protagonist who was white, according to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC).

That would mean that the other 50 percent were protagonists who were people of colour, one would assume - and yet, only 1 percent featured Native or indigenous characters, 5 percent were Latinx, 7 percent were Asian Pacific Islander/Asian Pacific American, and 10 percent were African American.

Your arithmetic skills should help you realise that these don’t quite add up to 50 percent.

In fact, the other 27 percent of children’s books featured a protagonist that was an animal - a fact which, to be honest, feels like a slap in the face.

Furthermore, a good number of books that have children of colour as protagonists are not written by people from that community (something which, when it does happen, is now called an #ownvoices book, a hashtag started by YA author Corinne Duyvis, who is bisexual and disabled, to highlight authentic stories).

Thankfully, there are important initiatives like We Need Diverse Books, which is intent on making change in the American publishing industry. Its mission is simple: to put “more books featuring diverse characters into the hands of all children”. Several organizations and festivals, such as Kweli, highlight and celebrate writers and illustrators of color.

The changes are happening, albeit in small, slow ways. For example, the CCBC’s 2018 list is an improvement from its 2015 list - the percentage of kidlit books with a black protagonist have gone from 7.6 percent in 2015 to 10 percent in 2018. Small, as I said, and slow, but change nonetheless.

But Arab American protagonists didn’t even make it onto either list, which didn’t surprise me one iota.

Call to action

American author Walter Dean Meyers, who wrote over 100 children’s books himself, said in a vaunted 2014 New York Times op-ed: ‟Books transmit values. They explore our common humanity. What is the message when some children are not represented in those books?”

It’s more than a question. It’s a call to action. Thankfully, the publishing industry, in the US at least, is becoming more diverse. Certain imprints and publishers, some established and some newly created, publish marginalised writers. These include Kokila Books, Lee and Low, and Heartdrum.

And teachers and librarians are actively engaging with authors themselves, so that we have direct communication outside of book lists and publisher’s marketing tools.

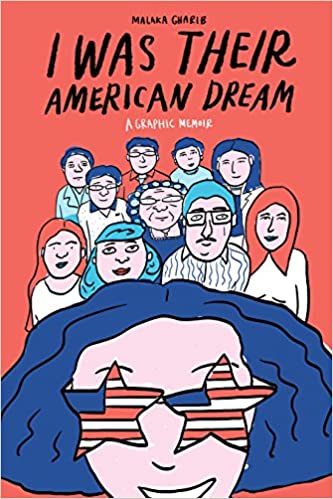

And what happens to stories that simply don’t adhere to the chalk outline? One of the best books I read in recent years was Malaika Ghraib’s graphic memoir, I Was Their American Dream (2019).

With compelling illustrations and a witty narration, Ghraib documents her upbringing in a family with a Filipina mother and an Egyptian father. It’s a solid example of what Thompkins-Bigelow meant by a “complete story”: Gharib’s book messes the borders of the chalk outline. It belongs on multiple shelves.

Perhaps the publication of this book signals a shift. Like the CCBC round-ups, maybe the numbers are slowly getting better.

After my first Farah book was published in 2020, the heartwarming messages I have received from Arab American parents had lifted me.

One of my favourite things is to sign the books to girls who are named Farah - the delight in their eyes, to see a girl who looks like them and bears their name, thrills me.

But I am one writer. And though I was already an established author, it still took me a while to find a publisher willing to support a book like mine. I can name dozens of emerging Arab American writers with brilliant books in the pipeline. I hope they will find publishers as well. Their stories matter too.

But that’s not enough. The ultimate goal, in my mind, is to collapse the shelves. What’s the point in assigning us all labels that limit our identities and marginalise our culture?

Books by white writers don’t get labelled in this way; it’s assumed all readers will enjoy them, which is true. So why does my little Palestinian American fifth-grader have to fit a particular identity to be adopted by a fourth grade teacher for her curriculum?

Like other people of colour, we also want our stories to be published and placed on store and library bookshelves, or woven into school curricula and lesson plans.

Not only because our own children need it and crave it, as my daughter did, but because a range of stories about our lives will disrupt the neatly contained image of Arab life which is routinely served up to other non-Arab children.

Farah Rocks New Beginnings by Susan Muaddi Darraj is available from Capstone

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.