Nation-building animation: The history of Arab cartoons

Arab children, across generations, haven't grown up with a single visual culture.

The wide eyes, dark hair, and stylish action sequences of Japanese anime existed alongside Disney's animal sidekicks, the Nubian cultural garb of Egypt's Bakkar, and the ancient Arabian aesthetic common to Islamic cartoons.

For decades, television channels across the Middle East have been filling out children's slots with content from around the world, Arabising them so specifically that most of those who grew up with 90s cultural staples like Captain Majid, the Arabic-dubbed version of the Japanese Captain Tsubasa, don't even realise they aren't originally Arab.

Animation was expensive to produce, so Arab channels were and remain flooded with international content. But homegrown, locally produced cartoons have a mighty history of their own, one that is more revealing than might be expected of a seemingly innocent medium.

Here, we take a trip through the history of Arab animation, and explore what the characters of our childhood can tell us about social debate and trends of the time.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Mish Mish Effendi: the Egyptian Mickey Mouse

In his 2021 book Arab Animation: Images of Identity, Omar Sayfo studies the history of Arab cartoons, revealing how cartoons engage in the construction and negotiation of national and religious identities.

“If producers took the time to invest in local animation, it was always to create something that told children about their own local, national, Arab, or Islamic identities,” Sayfo tells Middle East Eye.

Egypt’s answer to Mickey Mouse was no exception.

In 1914, the Frenkels, a Jewish family of Russian descent, were deported from Jaffa to Egypt's Alexandria, then a busling cosmopolitan centre, after the Ottoman administration in Palestine expelled Russian Jews they thought could become enemy spies.

By 1935, the three Frenkel brothers - David, Herschel and Shlomo Frenkel - had resettled to Cairo, where they established a successful furniture business.

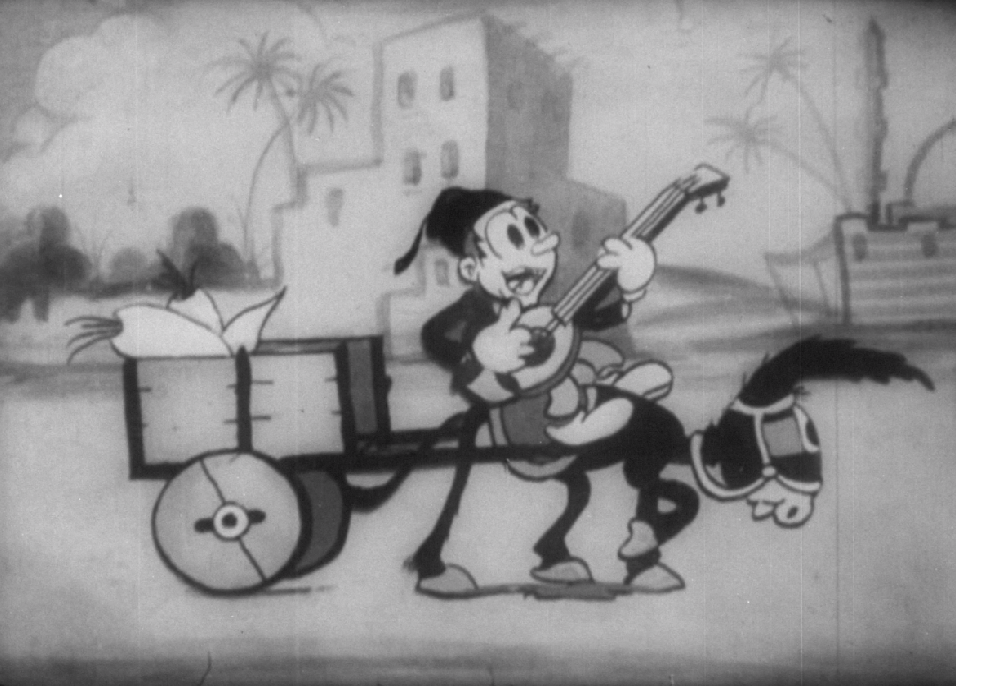

After hours, in a painstaking reinvention of frame-by-frame techniques, the Frenkel Brothers created their answer to Mickey Mouse: Mish Mish Effendi.

Frenkel Pictures debuted the suit-clad, fez-wearing Mish Mish Effendi in a four-minute episode in February 1936. Immediately dubbed the Egyptian Mickey Mouse by local papers, Mish Mish and his Betty Boop-style love interest Bahiyya were heavily localised to reflect a strong Egyptian identity.

By 1938, in the lead-up to World War II, Egypt’s war ministry had commissioned an episode for propaganda purposes, Al-Difa’ Al-Watani (The National Defence), in which Mish Mish rides to war on his donkey, raises funds (quite a bit of screentime is filled with the words "Donate to the National Defence"), and fires anti-aircraft missiles at planes attacking Cairo.

The Frenkels produced one animation film every year, as well as a number of animated commercials for Egyptian brands, until the family were compelled to leave Egypt amidst worsening social strife and a rise in antisemitic sentiment following the establishment of Israel in 1948.

The brothers moved to France, where they lived for the remainder of their lives and tried to revive Mish Mish as Mimiche, switching the mouse protagonist's fez out for a beret. The reworked show met with little success.

El Amirah Wel Nahr: A fairytale for Saddam’s Iraq

In 1980s Iraq, as the war with Iran raged and Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime built a consolidated media infrastructure, Iraqi TV’s children’s department aired short spots that - despite sharing the same general goal as putting Mish Mish Effendi on the frontlines - were more anti-Iran propaganda meets Tom & Jerry.

Episodes were short, cheap and low-quality imitations of the slapstick comedy of western cartoons, just with frequent, pointed attacks on Ayatollah Khomeini. The cartoons portrayed Iran's supreme leader as a bumbling buffoon, outsmarted and overpowered by Iraq.

In contrast, the only feature-length Iraqi animation under Saddam, El Amirah Wel Nahr (The Princess and the River) was repeated constantly, and became a staple of Iraqi childhoods in the 80s and 90s.

Released in 1982 with a $1m budget, a 90-minute runtime and animation outsourced to East Germany, the film is a Disney-esque adaptation of an old Mesopotamian tale.

After the death of their father the king, three princesses embark on a quest to pass three tests in order to gain the throne and become queen of the Land of the Two Rivers, unite the kingdoms of Sumer, and defeat the neighbouring country and its wicked ruler, the creatively-named ‘Eiran.

The film was a form of subtle propaganda, playing on a larger metanarrative of what it means to be Iraqi.

“It’s embedded in the historical thought that Saddam’s regime tried to establish, of reviving this Babylonian identity,” Sayfo explains.

“Iraqi society is quite diverse, and you need to go back a very long time to find a common ancestor that everybody agrees on. In literature and film production, Saddam tried to revive this Babylonian identity and mythology.”

Freej: the many faces of pre-oil Dubai

In a traditional Emirati neighbourhood - freej in the local dialect - four women representing a cross-section of pre-oil Dubai society navigate a rapidly modernising world, while holding on to Emirati identity and traditional values.

Freej, which first aired in 2006, was one of the first examples of Arab sitcom animation, a trend that swept through the region in the 2000s.

According to Sayfo, the four women were brought together to represent the diversity of pre-oil Dubai.

Umm Saeed has a thick Bedouin accent and drops verses of old Arabic poetry mid-conversation, Umm Allawi comes from a Persian (or Ajami) background, Umm Khammas is of East African descent, and the overweight absent-minded Umm Salloum is a stand-in for elderly Emiratis.

“All in all, Freej advocates for a modern Emirati national identity that fuses traditional values with modern achievements,” Sayfo explains.

Bakkar, with the Nile in his veins

By far Egypt’s best-known animation hero, the young Nubian boy Bakkar, along with his pet goat Rashida, were staples of Egyptian Ramadan TV from 1998 until 2007.

With an iconic theme song by famous Nubian singer Mohamed Mounir, Bakkar Egyptianises the country’s Nubian minority in a way that hadn’t happened before.

Up until the good-natured Bakkar emerged on screens, representations of Egypt’s Nubians in theatre, film, and TV were limited to derogatory blackface performances, or the jolly and simple servant.

Although today there are still examples of unfair and sometimes racist representations, the use of Bakkar's character as a vessel to teach children about morals, patriotism, and local culture was significant.

The theme-tune for the cartoon presents Nubians as an integral part of Egyptian society, despite the fact that they were, and remain politically, economically and socially disenfranchised.

“Ever since he was young / he has known in his heart and soul that he is Egyptian / the Nile runs through his veins / his country’s history is in his blood,” goes the song.

To understand why representations of Egyptian identity like Bakkar came to be, Sayfo says we need to take a look at the political context of the time, specifically the perceived need for narratives of unity to counter Islamist tendencies in society.

The 90s had seen increased social strife in the country, with clashes between the army and Islamist forces around Egypt, as well as several terrorist attacks throughout the decade.

Mubarak-era media narratives therefore pivoted to unity, harmony, and the portrayal of moderate Islam.

Stories of the Quran: Azhari moderate Islam

One implicit but consistent thread emerges when taking a close look at Arab cartoons: the threat of Islamist ideas of religion, and the attempt to offer alternatives in the form of educational entertainment.

From the mid-90s onwards, Egyptian television has invested in a robust collection of Islamic cartoons, including the 1999 series Qisas al-Anbiya (From the Stories of the Prophets), which received critical acclaim for creator Zeinab Zamzam’s use of clay animation.

Over the past decade, these have been supplanted by producer Mostafa el-Faramawy’s Stories of the Quran, with each season grouped under a different theme (including stories about animals, miracles, and women). The series advocate an Islam of tolerance and acceptance of diversity.

In one episode of Stories of the Quran, for instance, the characters travel to India, where they learn that cows are sacred to Hindus. The captain, voiced by celebrated actor Yehia El-Fakharany reflects: “We should respect the beliefs and culture of others. This is what our religion teaches us.”

Sayfo explains that Al Azhar, the Sunni world's leading institution for Islamic learning, which has the authority to censor all religion-related content, possesses such strong cultural power globally, that Egyptian Islamic cartoons have massive export potential.

'Most producers will self-censor automatically'

- Omar Sayfo, author

As a result, these cartoons achieve much greater success than those produced elsewhere. According to Sayfo, Lebanese-Iranian Shia productions succeed in Shia markets, and Saudi cartoons sell to Sunni markets, but both are seen as politically loaded.

“Meanwhile, Al Azhar specifically and Egyptian Islam more generally is regarded as less politically motivated. It’s much more neutral, and not a political threat."

Sitcoms and (self-)censorship

Following the success of Freej, a "sitcom animation craze" gained momentum and within a decade, more than 30 animated sitcoms were produced across the region.

One of the most successful of these sitcoms, at least in terms of longevity, was the Kuwaiti Yawmiyat Bu Qatada wa Bu Nabeel (The Daily Life of Bu Qatada and Bu Nabeel), which aired from 2006 to 2014.

Steeped in stereotypes of the different players in the Kuwaiti social and political scene, the series followed the misadventures of Bu Qatada, Bu Nabeel, and Bu Meshal, and attempted to hold up a satirical mirror to local public discourse.

One character is obsessed with sharia law, the other embodies the loss of heritage for assimilation, and the third worships US commercialism.

Even when the series pokes fun at local politics and society, it does so carefully, in a dynamic mirrored across the region. “It always goes back to self-censorship,” Sayfo explains.

“Every producer knows their limits; they know what they’re allowed to criticise and what they’re not.”

“Because of how expensive animation is to produce, you can’t afford to take big risks. Most producers will self-censor automatically. They certainly reflect on social and political issues, but only on issues that are already widely discussed in the local scene.”

Badr and a new Arab anime

Few things have gripped Arab childhood imagination as strongly as anime. The massive importing of Japanese productions starting the 80s was due to a number of reasons, including that they were cheaper than US shows.

“In the Cold War era, it wasn’t expressly political to purchase animations from Japan,” Sayfo says. While different Arab countries would predominantly import cartoons from the bloc they were aligned with, Japanese anime was politically neutral.

For Arab censorship offices, children’s anime carried very little risk of ruffling any feathers.

“You knew it wouldn’t include anything that a conservative Arab point of view would need censored,” Sayfo explains. “You could just buy it, dub it, air it, and be happy with it.”

In 2017, Badr, the first Arab anime series, aired on Qatar’s Jeem TV.

Produced by Al Jazeera-owned Bein Media Group, Badr follows a young boy in a small pearl-diving town in the pre-oil Gulf. The series blends fantasy with traditional values and a hero narrative with a distinctly Arab cultural identity.

It is the same bet wagered by 2021 Japanese-Saudi film The Journey, a historical epic based in pre-Islamic Mecca, where an underdog hero must protect his city and the Kaaba from an advancing army.

Both productions benefit, not just because they rely on the familiar visual culture of anime, but from the massive investments they could make in quality.

The Journey was animated in Japan, and Badr owes its visual sophistication to the know-how its production company purchased with its 2016 acquisition of US entertainment company Miramax Films.

“When we’re talking about animation, quality counts, and you can buy quality with money,” Sayfo says. “If you want to produce something that draws the attention of children especially - who are used to western productions - you need to invest a lot of money.”

But even with money on your side, recent attempts at competing on a global level, including The Journey and 2015 UAE-produced Bilal, generally fall flat.

Commenting on Bilal, Sayfo says: “They had great ambition, they invested a tremendous amount of money, it was a good quality production. But it still didn’t really sell well. Because it’s very hard to compete with Pixar and Disney, even if you purchase the know-how.”

The history of Arab cartoons has run in cycles, according to Sayfo: the 2000s boom in sitcom animation, the growing market for Islamic cartoons, and - after the Arab Spring - the trend of online revolutionary animations.

According to Sayfo, we’re waiting on the next big wave. “And it always comes. There is always a next generation, there are always new stories to tell, there are always creative people who want to push the animation industry.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.