Paradise lost: Why the ideal of Al-Andalus found a place in Arab poetry

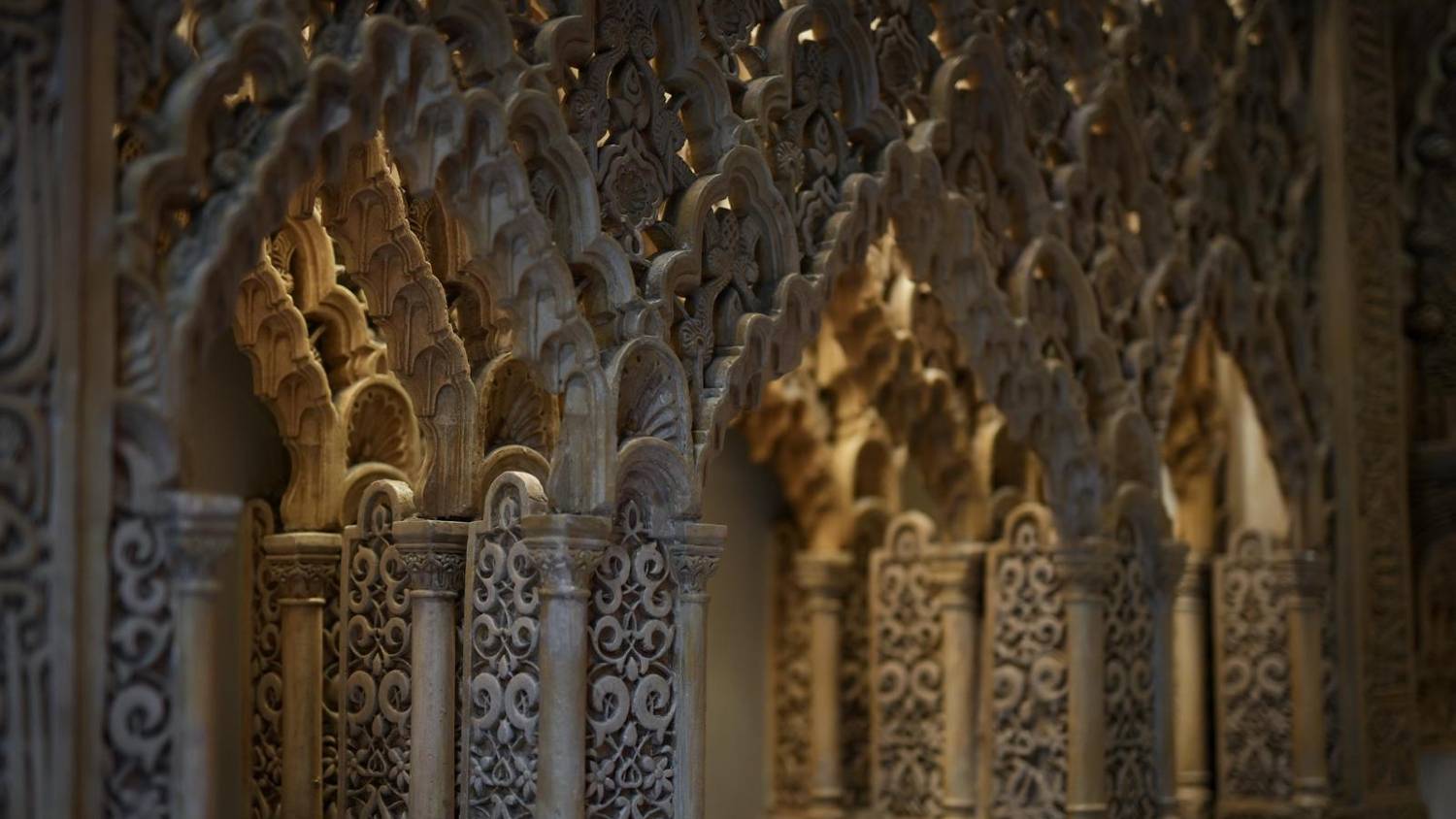

In his 1961 poem Granada, named after the Spanish city in the heart of Andalusia, the great Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani tells his beloved that, "At the entrance of Alhambra was our meeting."

The reference to the city's palace and fortress complex recalls an era that for many Arabs represents a golden age in their culture.

In their memory, Al-Andalus was a beacon of light on a dark continent. A place of architectural marvels, intellectual flourishing and where there was a degree of religious tolerance rarely seen elsewhere during the medieval ages.

The history of Al-Andalus was also a counter argument to the 19th and 20th century imperialist notion that the Arab world was in need of civilisation.

Qabbani, like other poets of Muslim and Arab origin, found refuge within this history and the memory of Al-Andalus became a place where Arab glory would remain intact amid the dark realities of the present.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

His feeling of pride is captured succinctly in the same poem, in which he writes:

She said: Alhambra! Pride of my ancestors glowing,

Read on its walls my glories that shine and show.

From Abd al-Wahab al-Bayati, to Muhammad Iqbal, Ahmed Shawqi, Adonis and Mahmoud Darwish: Al-Andalus has served as an image of Atlantis; one of a lost jewel and, crucially also, of a north star that can guide Arab and Muslim civilisation back to its former glories after the damage inflicted on it by colonialism and the modern Arab regime.

Pride in the past

While Muslims lost physical control of their territories in Spain in 1492 and the victorious Christians worked hard to erase their memory, the depth of Islamic culture on the Iberian peninsula proved difficult to erase from the European cultural memory.

This was in part because of the profound impact Muslim Spain had on European thought, with scholars like Ibn Rushd (Averroes) influencing later Christian pre-reformation thinkers like Thomas Aquinas.

The existence of an advanced Muslim civilisation in Spain, recorded by Europeans themselves, provided a powerful counterargument to imperialists from the continent who justified their colonial endeavours in the Islamic world in the 19th and 20th centuries on the basis of civilising underdeveloped native populations.

“Britain and France justified their colonial conquests by claiming that they were actually liberating the colonised peoples… and giving them civilisation, economic development, rights (and) education,” University of Arizona Professor Yaseen Noorani told Middle East Eye, adding that Al-Andalus, "truly achieved all the things that Europeans claim for their colonies."

It is no surprise then that so many poets from India to Egypt, all countries struggling with European interference, found solace in the ideal of Al-Andalus and used its memory to remind their people of a glorious Islamic and Arab past.

As Noorani writes in his paper, The Lost Garden of al-Andalus: Islamic Spain and the Poetic Inversion of Colonialism, this memory travelled far beyond the Arab world.

The Urdu and Persian language poet and spiritual father of the state of Pakistan, Muhammad Iqbal, travelled to Andalusia during the heart of the Indian independence struggle in 1933 and prayed at the Great Mosque of Cordoba, which had by then long been used as a cathedral.

A result of the visit was his poem Masjid-i Qurtubah, in which he describes the enlightening impact of Andalusian Islam on Europe.

Flowing waters of the Guadalquivir,

upon your bank stands one who dreams of another time.

A new world lies behind the curtain of Divine Decree;

Its dawn is unveiled in my glance.

Should I lift the veil from the face of my thought,

Europe shall not withstand the brilliance of my son.

His Egyptian contemporary Ahmed Shawqi, had a similar experience while visiting Andalusia earlier in 1919.

A dream of a better life

Such idealisation of Al-Andalus is not a modern phenomenon and stretches back hundreds of years to even before the fall of Granada at the culmination of the Reconquista in 1492.

In the 13th century, the Andalusian poet and scholar Abu al-Baqa ar-Rundi, wrote about the fall of Muslim Andalusian cities to advancing Christian forces in his poem An Elegy to al-Andalus (Ritha' al-Andalus).

In it, he speaks of mosques recast as cathedrals and prayer niches left lifeless and also describes the beauty of the cities now in Christian hands.

A pretty lady, splendid as sunlight,

Her beauty just like coral and jewels bright,

Dragged off by infidel for rape most vile,

Her heart perplexed, she’s crying all the while.

Another Andalusian poet, the 11th and 12th century native of Valencia, Ibn Khafaja, wrote in his poem O People of Andalusia:

The eternal Paradise is in your homes,

And if I had to choose, I would have chosen this

The idea of Al-Andalus, reinforced by poets who lived during its heyday, provides a contrast to the circumstances many Arab writers found themselves in during the 20th century.

Harvard scholar William Granara, states that for Arab nationalists Al-Andalus represents a period of political stability, cultural and intellectual flourishing and tolerance, “a mythical discourse [that] involves the premeditation of and negotiation for a better life”.

For the Arab poet of Qabbani’s era, sources of joy and pride were few and far between, as Arab states lagged behind Europe in terms of material development and political stability.

Despite serving as a diplomat in his younger years, the Syrian poet became an outspoken critic of Arab governments over their stifling of freedoms, and their inability to resolve the Palestinian issue and to economically develop their countries. Al-Andalus in this context became the symbol of what could be.

Connecticut College academic and author Waed Athamneh has written that, “Al-Andalus has always been and will always be the (ruins) some Arab poets will cry over or upon, the abode of the beloved who is no longer there... Spain is the lost Paradise”.

This longing for a better life rooted in the nostalgia for Al-Andalus continues to influence the works of Arab poets and writers.

Reality check

However, the idealisations of Al-Andalus are just that, idealisations. The degree to which the reality of Al-Andalus corresponds to nostalgia is a subject of debate amongst Arab scholars.

Abdelkhak Najmi, a Moroccan researcher and translator based in Granada, draws similarities between the politics of Al-Andalus and the failures of today's Arab states.

"We know that in Al-Andalus there was also the time of the taifas, Muslim rulers that were divided, always fighting each other and, in some cases, allying with the Castilian enemies,” Abdelkhalak said.

“It is the same thing that is happening now in Libya for example, or in Yemen,” he added.

“Some say... the Arab world is living like under the taifas. Some Arab countries are allying with foreign powers to divide and occupy other Arab countries."

That reality check puts the memory of Al-Andalus into perspective. Less a historic goal to emulate, Al-Andalus instead provides the perfect literary device for talking about contemporary issues.

Reality aside, that literary device is frequently called upon by poets to talk about colonialism or the loss of their homeland, as demonstrated by Mahmoud Darwish in the way he draws parallels between the losses of Palestine and Al-Andalus.

“In every poet, there is an Andalus," Darwish would say in an interview in 1991 and in his poem, The Violins Poem, he writes:

The violins cry for the Arabs departing Andalusia.

The violins cry for a lost epoch that will not return,

The violins cry for a lost homeland that could be regained

In the loss of Arab Spain in 1492 and the nostalgia born from that loss, Darwish foresees the fate of his own Palestinian homeland.

In a while I'll emerge from the wrinkles of my time,

alien to the Levant and to Andalusia (...)

Adam of the two Edens,

I who lost paradise twice

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.