Orientalism, exoticism, deception: The story of the Arabian Nights

They are probably the most famous set of stories about the medieval Arab world known in the western world, but the origin and authorship of the Arabian Nights are mired in controversy.

The tales were enhanced by a meeting between Hanna Diyab, a Syrian writer and storyteller, born in Aleppo around 1688, and a French art collector. Diyab had initially hoped to become a Maronite monk, but on abandoning this path he returned home, where he met the Frenchman, who employed him as an interpreter.

In the early 18th century Diyab travelled to France, which was under the reign of the Sun King Louis XIV, to whom he was introduced at the Palace of Versailles, along with other members of the high aristocracy.

Diyab no doubt possessed charm and attracted curiosity among this new milieu.

Thanks to Elias Muhanna’s recent translation of Diyab's memoir, The Book of Travels, we know that in 1709 he encountered Antoine Galland, a French philologist and “Orientalist” at large, who made several visits to the Ottoman Empire. Galland had translated the story of Sinbad the Sailor, which was published in 1701 and quickly became popular in France. There was no better timing for his meeting with the Syrian traveller.

When the pair met, the Frenchman was in the process of translating an even more ambitious work, The Thousand and One Nights (Alf laylah wa Laylah in Arabic, hereafter referred to as Nights).

Galland's source material was a 14th or 15th century Syrian manuscript that needed more stories, and, for a European readership perhaps, more panache. And that's where Diyab stepped in, recounting stories he knew, likely drawing on his own adventures.

After Diyab's contributions to the final text, Galland encouraged him to return to Aleppo and bask exclusively in the glory that the book would bring. He was granted no acknowledgement in the following tomes of Galland’s Nights, the last volume of which was published posthumously in 1717, although his contribution was recorded in Galland's private notebooks.

After returning to Aleppo, Diyab married and entered the cloth trade, establishing himself as a successful merchant.

Debates over authorship

Deceit is at the heart of Nights, not only as one of the many devices used by the resourceful Shahrazad, who chooses to marry the murderous King Shahryar to save other women from a dreadful fate, but also in the presentation of Nights as a truly "Eastern" collection of stories.

Were the cherished stories of Aladdin, The Ebony Horse and Ali Baba - which appear nowhere in earlier versions of the compendium - Diyab’s or Galland’s invention?

Controversy over authorship and reception of Nights has long been a topic of contention, particularly when it comes to the cultural impact and resonance of the stories. The collection is so closely associated with fantastical tales from a certain version of the “East” that one forgets it was more popular in the West than in its supposed lands of origin.

The precise evolution of the Nights compendium prior to Galland’s translation remains opaque. Galland relied on a Syrian text (one of four extant corpuses), which did not include many of the tales he and his publisher later added.

A 10th-century reference to a Persian text called Hazar Afsaneh (A Thousand Tales) may lend weight to the assumption that the Arab text comes from earlier provenances via Persia and likely India, as the literary devices and other cues from Shahrazad’s story point to elements of classic Indian literature.

The immediate success of Galland’s translation of Nights coincided with the revival of the genre of fairy tales in western literature. Giovanni Francesco Straparola had published The Facetious Nights by the mid-16th century, and in France, Charles Perrault’s versions of Cinderella and The Sleeping Beauty were both published in 1697.

'Cultural resonance'

It’s no surprise, then, that Galland’s Nights became a literary bestseller in a society hungry for entertainment and magic.

A "Grub Street" version of the collection followed Galland's and the Frenchman also inspired others to follow suit; three-year-long serialised versions appeared in German newspapers, starting in 1712, Italian (1722), British (1723) and Russian (1763).

The cultural resonance of Nights in European society was near immediate and travelled through the Enlightenment, Romantic, Victorian and imperial ages. The text generated pastiches and pantomimes. Put simply, it captured the imagination.

During the Enlightenment, it inspired writers such as Montesquieu, in his Persian Letters, and Voltaire’s Zadig to use a fictional “oriental” setting in their denunciations of oppression, and to advocate for liberal political reform domestically.

Stripped from its most adult-leaning content, the tales were regularly read to children in England, to the extent that they became a classic of literature by the late 18th century.

They also fuelled the Romantic mind, which echoed with wanderlust, an adoration of the irrational, and the longing for intense feeling, whether love or betrayal. They encouraged writers to expand their "Grand Tour" travels beyond Italy and Greece, and the book stayed in the minds of Wordsworth and Coleridge, to name just two.

Theophile Gautier, Joseph Roth and Edgar Allan Poe both retold Nights, imagining a “thousand and second tale” to Shahrazad’s prolific stories, reminding us that significant texts lend themselves to multiple imitations and retellings, as the Homerian epics have.

The Nights can be read through multiple lenses.

It is “a source of pure narrative pleasure, as a means to deliver didactic lessons, and as an instrument of political critique,” wrote Paulo Lemos Horta, the author of Marvellous Thieves: Secret Authors of the Arabian Nights, in his introduction toThe Annotated Arabian Nights: Tales from 1001 Nights.

Orientalism

And while storytelling remains a power connector and a bridge across cultures, the cultural success of Nights in the West can also be understood from the point of view of expanding colonial enterprises, particularly France and the UK during the 19th century.

To feed a collective projection of what is "Oriental", colonial authorities needed to build and rely on a narrative that utilised "othering" and "exoticisation"; the perception that there was something uniquely different in peoples from newly acquired territories, which justified their treatment in ways not acceptable in Europe.

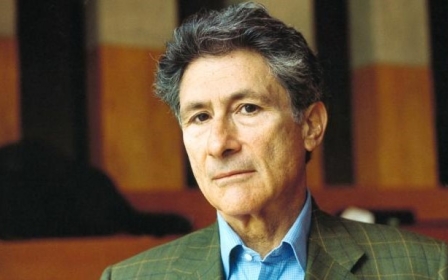

Orientalism is a library of ideas, which “explained the behaviour of Orientals; they supplied Orientals with a mentality, a genealogy, an atmosphere; most important, they allowed Europeans to deal with and even to see Orientals as a phenomenon possessing regular characteristics,” wrote Edward Said.

In many ways, characters in Nights “orientalise the Orient” and display a formidable range of human emotions, allowing western readers to gravitate towards the cunning, cruel, deceitful and licentious.

The text mattered more to European institutions and societies and their self-validating gaze than to the lived reality of Arabs during these centuries.

Between 1838-1840, Edward Lane produced a new translation of Nights based on an Egyptian compendium (the “Bulaq”, or Cairo manuscript). This gained even more popularity when the UK invaded Egypt in 1882. The text (rendered as Arabian Nights in English since the early 18th century) served then as a quasi-guidebook to Egyptian customs and society.

The Lane translation was then overshadowed by Richard Burton’s unexpurgated translation in 1885, which offered sex, scandal and Victorian-era pornography (Burton was accused of having plagiarised the work).

The tales were adapted to the media of the day, from book folios to enriched visual illustrations, and academic commentaries.

Jorge Luis Borges wrote about these histories in The Translators of "The Thousand and One Nights" (1934), discussing the problems of veracity and hybridisation in the “production” of literature such as Nights.

The late 19th century also saw the emergence of Nights-inspired “oriental” themes in music, for instance, Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade in 1888, and in paintings by artists such as Eugene Delacroix and Jean-Leon Gerome.

A modern retelling?

Yet in more recent times, Arab, western and south Asian writers are turning their creative attention to Nights, retelling its stories through the prism of their own memories and cultural heritage. Egyptian Nobel Literature laureate Naguib Mahfouz offered one such contribution. Others have addressed the role of female agency in the compendium.

“The transmission of these stories has always been propelled by women,” said Yasmine Seale, first female translator of Nights (published in 2021), in a recent interview.

Salman Rushdie, who based one of his books on an unfolding tale reminiscent of Nights, noted the absence of religious motifs in the tales.

“Lots of sex, much mischief, a great deal of deviousness; monsters, jinn, giant Rocs; at times, enormous quantities of blood and gore; but no God,” he wrote.

Nights are indeed a story of literary migration, from India to Arab lands via Persia, to France, to Britain, and the world, from Hanna Diyab to Hollywood’s Will Smith (who played the genie in a recent version of Aladdin).

At each stage on that journey, authors have added their own elements, and contained within those imaginings are their own biases, prejudices and world views.

For the reader, Nights has changed our appreciation of plot-driven storytelling and of viewing stories as endless scaffolding of the imagination.

Shahrazad remains the timeless voice of an unreliable but enthralling narrator, one who sparks the notion of possibility and mended fates – whose ending is far from over.

Editor's note: This article has been updated to clarify that the Grub Street version of the Arabian Nights followed the one produced by Antoine Galland

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.