From Babel to Berlin: How Arabic literature can unite the world

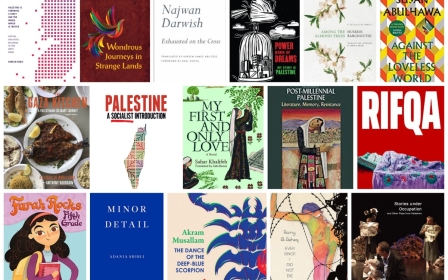

For much of the 20th century, Arabic novels (especially ones written by women) were deprived of opportunities for critique on the global literary stage due to limited translation. Today, translated Arabic works in the English-speaking world have surged amidst a vexed global, commercial and cultural climate.

Yet an enormous discrepancy still exists between the number of works that have been and are being translated, and the few that win awards and receive global literary recognition.

Inspired to acquaint readers with a richer Arabic literary experience, Sawad Hussain and Marcia Lynx Qualey, fellow aficionados and translators of Arabic literature, hosted a three-day digital literary festival titled Bila Hudood: Arabic Literature Everywhere.

From 9-11 July, the inaugural festival showcased five hour-long panels on Arabic literature in Berlin; African narratives in Arabic publishing; memoirs; food-writing; and young adult literature, as well as providing a platform for as-yet untranslated gems.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“I think a lot of European and American panels about Arabic literature are country-based: the ‘Iraqi literature panel,’ or they are issues-based - about refugees in literature. This festival gives a lot more elbow room to literature,” Lynx Qualey, who is also the founder of the translation community blog ArabLit, told MEE.

She added that the festival was a chance to engage with audiences in a new way, given that audiences have become more familiar with online events now.

Bila Hudood (which means “Without Boundaries” in Arabic) also presented an opportunity for translators to reach out to potential publishers. Panels were followed by video pitches by translators about books they love and want to translate. The shorts ranged from experimental video art to more straightforward, persuasive pitches created by translators.

'What we wanted was an opportunity just to show how high and long and high and deep the body of Arabic lit is. It's so much longer than Naguib Mahfouz or the 1001 Nights'

- Sawad Hussain, festival organiser and translator of Arabic literature

Some examples include a genesis story of the Earth taking the form of a vast cosmic female seagull; a book on a blasé Egyptian immigrant working as a housing officer for a local council in London whose life gains meaning once it collides with a young Syrian refugee; and a poetry collection representative of the Palestinian community that remained on their land after the Nakba of 1948, among others.

“Bila Hudood is such a fantastic opportunity to come together with readers, writers, translators and publishers to share our love of Arabic-language literature,” Kuwaiti-American author Layla AlAmmar told MEE on pitching Kuwaiti novel Wasmiya Comes Out of the Sea by Laila AlOthman.

“This novel [that I’m pitching] is very dear to me and I would so love to translate it and share it with the world.”

The virtual format also meant that a global audience could connect with prose writers, playwrights and poets from the Middle East and beyond, via panels moderated by key members of the industry, from authors to translators and editors.

“What we wanted was an opportunity just to show how high and long and high and deep the body of Arabic lit is. It's so much longer than Naguib Mahfouz or the 1001 Nights,” said Hussain in the introductory remarks.

“Our topics, which range from food writing to young adult literature, are fresh, thought-provocative and reflective of what is happening in Arabic publishing these days.”

One of the festival’s aims was to help elevate Arabic literature to an equal footing with other “world literatures” - a status the event certainly went one step towards achieving.

The three-day festival was packed with raw conversations on writing from an array of experts, leaving this writer at least feeling invigorated and hopeful for the future of Arabic literature in translation.

Arabic literature in Berlin

Berlin has rapidly transformed into a hub of Arabic-language literary production in the past seven years, according to Egyptian prose writer Haytham El-Wardany. Arriving in the 1990s because of a romantic relationship, he has since remained, bearing witness to its transformations caused by the Arab uprisings and subsequent migrations that flowed into the seemingly liberal, multicultural mecca.

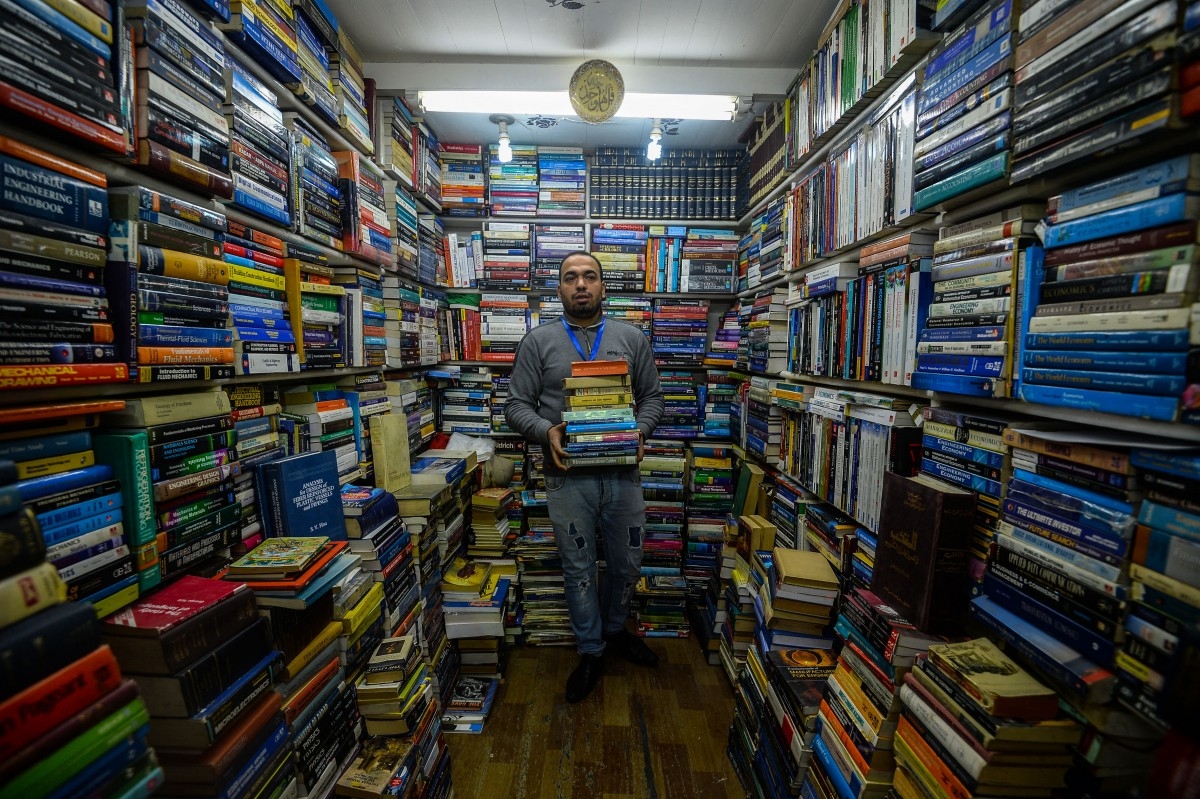

During the Arab literature in Berlin talk, he was joined alongside playwright Liwaa Yazji, and Arabic-German translator Sandra Hetzl, in a panel moderated by Arabic-English translator Katharine Halls. The event was in association with Khan Aljanub, Berlin’s leading Arabic bookshop.

The three panellists, all residents of Berlin originally from the Middle East, spoke about their journeys to the city, the infrastructure that supported them, their audiences, as well as the challenges of being an Arab writer in Berlin.

El-Wardany, the Berlin veteran of the group, talked about the “representation trap” that many Arab artists are pulled into right from the get-go: the expectation to personify the pain of failed revolutions and war. Yet, many also try to evade this ambush.

“We thought about: How to do what is not expected, but what is needed to be done? And what does it mean to write catastrophic events? What are the different modes of writing available and… is it helpful to write it down?” El-Wardany said.

'What does it mean to write catastrophic events? What are the different modes of writing available and… is it helpful to write it down?'

- Haytham, El-Wardany, author

Yazji, who joined the livestream from Syria, moved to Berlin in 2016 to work on a writing project for a TV series on the Tempelhof area, a former airport “where refugees were parked”, and which she calls a “modern tower of Babel”. She said she followed the inspiration of the "tides of Syrian refugees" since she moved to Berlin from Beirut.

In 2018, Yazji won the Berlin Senate stipend for non-German literature, which she describes as her “landing in Berlin”, an impetus to relate to the city and a sign to work on her project in Berlin, not elsewhere.

Her current project, Trash, is a novel set in Aleppo at the height of the 2015 siege and follows the love story between a quixotic protagonist who tries to show love to his city of Aleppo by cleaning up garbage, and his romance with a school headmaster.

This year Hetzl served on the jury for the stipend as the first person who could understand Arabic. She originally moved to the city for Art School a few years after El-Wardany’s arrival in the early 2000s, and was allured by Arabic-to-German translation, which she said probably wouldn’t have happened in another place. Since then, she has translated short stories, poems and non-fiction by writers ranging from Rasha Abbas, Kadhem Khanjar, Aref Hamza, Bushra al-Maktari, Aboud Saeed, Assaf Alassaf and Raif Badawi.

The panellists each read a piece of their work in three different languages (German, Arabic, English), starting with Hetzl who read two passages in German from a short story by Rasha Abbas, then by Liwa who read a long poem she wrote in Amsterdam when thinking about her grandmother.

Lastly, El-Wardany read in English a passage from his latest short story collection Things That Can’t Be Fixed which Katharine is currently translating.

In the passage he read, a foreigner arrived in Berlin and explores a green woodland that leads him to a lake:

Every so often the sounds would disappear so often entirely to be replaced by a thick silence from the lake, a silence unlike any I had ever heard.

These literary truths

In Dunya Mikhail’s book, The Beekeeper of Sinjar, which she co-translated with Max Weiss, she travelled to her native Iraq for the first time since departing more than 20 years ago, to visit the camps and graveyards of Yazidi women who escaped the clutches of Islamic State and lived to tell their harrowing survival tales.

“Usually people who go back home visit relatives and have fun, but I went for this particular purpose and it was a unique visit,” she said.

This form of “truth writing”, such as memoirs, non-fiction, or autobiographical writing, has exploded in the Arabic literary scene in recent years, with tales weaving together deeply intimate family histories that intersect with broader political forces.

The discussion in the panel title, "These literary truths: on life writing and memoirs" in Arabic, was moderated by Rima Rantisi, co-founder of the Rusted Radishes literary magazine in Beirut. The panel focused on the concept of writing “truth” and was specifically tailored to each author’s own journey and projects, with Iraqi novelist and poet Mikhail reading an excerpt of her book as well as a reading by Egyptian writer Amr Ezzat.

Both authors were joined by the curator and artist Maha Maamoun, one of the co-founders of the Kayfa Ta project, founded in 2012 in the vacuum of the Arab uprisings, and which supported a number of artists, including Ezzat.

The bilingual Arabic-English project emulates the popular form of how-to manuals as an “intervention in publishing” and as a response to some of their own - and the region’s - pressing questions.

Some books include How to Disappear (2018) by Egyptian author Haytham El-Wardany, translated by Jennifer Leigh Peterson and Robin Moger, and How to Mend: Motherhood and its Ghosts (2018) by Egyptian poet and novelist Iman Mersal, translated by Robin Moger.

Ezzat’s contribution to the How To series - How to Remember your Dreams - blends stupor and prose, layering “sleeping dreams, day dreaming, hope, ambition, fascination, political ideology, faith and religious beliefs and experience”. The act of writing it, he said, was like “remembering your life through the vague memory of dreaming, which is not aimed for truthfulness”.

As for Mikhail, the motivation for her to write this book as non-fiction came after she stumbled upon her protagonist, the beekeeper Abdallah, in the process of her research into the Yazidi genocide, when she was speaking to relatives and friends. Abdallah had been translating from Kurdish real-life stories as he came across them. When she heard his own story, about how he had rescued clutches of women from Islamic State, Mikhail said she had to write about him.

"Their stories didn't kill me. But I would die if I didn't tell them to you,” she said.

She also included poems in her novel, which she wrote as a cathartic reflex on her trip to Iraq, instead of crying.

“I debated with myself: should I keep these in the book? I wanted the focus to be their stories and not my pain, but I thought that if it is giving me rest, then maybe it will give the reader rest too.”

Young vision

The body of Arabic young adult literature remains relatively small, but it has a vibrant history tracing back to the turn of the 20th century. Existing in many forms - short stories, book series, magazines, stand-alone novels - it has become a constantly evolving category, thanks in part to the authors that participated in the final panel.

The discussion focused on the genre of YA, the writing process, their inspirations and future hopes for their translated or soon-to-be translated works.

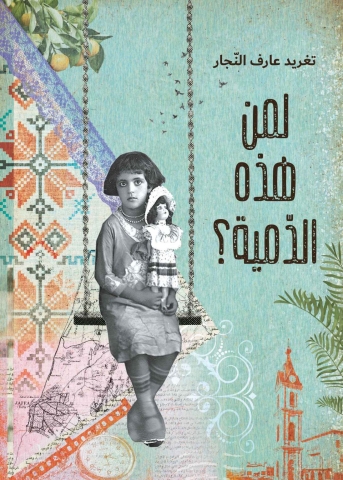

Taghreed Najjar, a pioneer of modern children’s literature based in Jordan but originally from Palestine, read an excerpt in Arabic of her latest novel titled Whose Doll is This? The novel was inspired by a family photo of her family in Haifa in the 1930s.

“I was fascinated by this picture which we had forever and I looked at my mother who was holding a doll with piercing eyes,” Najjar, the owner of al-Salwa publishing house in Jordan, which specialises in Arabic picture books, told the audience. The story is not biographical, but blends many elements of truth on the intergenerational story of Palestinian women living in the diaspora, specifically Chicago.

Mainly, it centres around a conversation between her mother and the doll who haunts her, by asking: "Why didn’t you take me with you when you left Haifa?".“Through this, we understand why they left,” Najjar said, referring to the forced expulsion at the hands of Israeli soldiers.

Syrian novelist and YA writer Maria Dadouch, whose work also stems from the context of war, and addresses sensitive topics such as PTSD, schizophrenia, social injustice and bloodshed, also struggles with grabbing the attention of her young readership.

“I can manage if I am a good writer to get their attention by honestly depicting my young characters human experiences… which are universal,” she said.

The excerpt she read was from her award-winning Arabic novel I Want Golden Eyes, translated by Hussain and Lynx Qualey, and forthcoming with University of Texas Press. Set in a dystopian future, it explores what happens when the power of science falls into the wrong hands, and specifically when the protagonist Diala, who belongs to a group banned from reading, attempts to smuggle some books past a checkpoint.

The writers discussed the current digital frenzy that has resulted in decreased readership of classic texts. Yet the magic of a good story is still very much alive, according to Egyptian translator and writer Ahmed Salah al-Mahdi, who still enjoys books written for YA like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and Alice in Wonderland.

Al-Mahdi was inspired by his grandmother's stories involving djins, demons, and black magic to write his popular Reem Into the Unknown (Knotted Road Press, 2019), a suspenseful novel about a man who buys a black cat that turns out to be the worst decision of his life.

One prevalent theme throughout the festival was the desire for more Arabic literature in translation, with authors echoing the fact that seeing their works in English would increase a cultural understanding and break stereotypes.

“I want others to realise that human universal experiences and feelings do apply to Arabs, I want other societies to see us for who we really are,” said Dadouch.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.