The Argentinian Egyptologist who saved hundreds of Nubian treasures

Born in 1896 in the tiny Argentinian town of Colonia Mauricio, around 300 kilometres from the capital Buenos Aires, Abraham Rosenvasser would make his name on the other side of the world, in the deserts of Nubia in southern Egypt and northern Sudan.

Considered the father of Egyptology in Argentina, Rosenvasser was the leader of an Argentinian mission, which in the early 1960s took part in the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia, threatened by the construction of the Aswan High Dam in Egypt. There he rescued hundreds of artefacts, cementing his place among the roll-call of great Egyptologists.

“His personality was extremely sober," remembers Elsa Feher, a physicist and Rosenvasser’s daughter. "He had come from a very harsh place, time and moment.”

Rosenvasser’s parents were originally from a village in what is now Ukraine. But in 1891 they had to flee anti-Jewish pogroms and ended up putting down roots in a small Jewish colony in inland Argentina, where they were allocated a 180-hectare plot of land to farm.

During his childhood in the colony, Rosenvasser used to ride to school on horseback with two of his brothers, Benjamin and Jacobo. With the exception of a library they had in the settlement, he grew up in an environment marked by harsh living conditions and austerity.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

It was not until he was ready for secondary school, which was not available where he lived, that Rosenvasser moved to Buenos Aires, in a leap that soon changed his life.

There he began to immerse himself in the study of subjects such as Egyptology, the origins of monotheisms, the East and its ancient languages, ethics and morality. Along the way, he taught himself how to read hieroglyphs by studying from an English manual in the mornings. He also spoke German, French, English and Italian, in addition to Spanish.

In 1933, Rosenvasser had a stroke of luck when a small fragment of an undeciphered papyrus found in a museum in Argentina came into his hands. Thanks to what he had been able to learn about hieroglyphs, he discovered that it was part of the tale of Sinuhe, considered one of the finest works of ancient Egyptian literature.

This finding earned Rosenvasser the respect of international Egyptologists and ultimately the opportunity to travel to Nubia, where he was given the task of saving the Aksha temple, built by Ramesses II, one of the greatest pharaohs of the New Kingdom.

Part of what Rosenvasser was able to recover is now on display at a museum in the city of La Plata, near Buenos Aires – the only ancient Egyptian collection of such magnitude in Latin America.

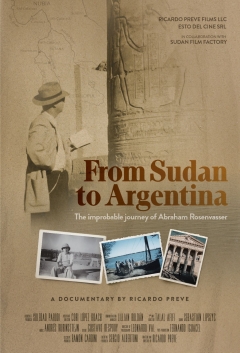

The story of how these remains travelled from the desert of northern Sudan to Argentina is the focus of a new documentary by the renowned Argentinian filmmaker Ricardo Preve, From Sudan to Argentina, which delves into the singular figure of Rosenvasser.

“His was a project that takes us back to our common humanity,” Preve told Middle East Eye. “The project of archaeologists who wanted to save our stories of the past.”

From Argentina to Sudan

When Egypt decided to start building the Aswan High Dam in 1960 to regulate the flooding of the Nile, Unesco launched an international appeal to mobilise and save the archaeological treasures of the area, which were threatened by the great Lake Nasser that would form behind the massive infrastructure.

In all, 40 archaeological missions from around the world organised salvage campaigns and worked in the region for 20 years to excavate, dismantle, move and in some cases reconstruct 20 monuments of great value, according to the La Plata museum.

One of the monuments at risk was the Temple of Aksha, built around 1250 BCE on a stretch of the western bank of the Nile as it flows through Sudanese Nubia.

“Aksha was one of the first temples, perhaps the first, where the deification of Ramesses as a god is documented in Nubia,” Elba Perla Fuscaldo, an Argentinian Egyptologist and a disciple of Rosenvasser, told Middle East Eye.

Although most of these missions came from Europe and the US, one of the countries that responded to Unesco's call was Argentina, which formed a mission led by Rosenvasser.

“When the Unesco call came, he jumped at the chance. Here was an opportunity to spend some time in a place that had always been in his mind,” Feher said.

The expedition carried out three campaigns, between 1961 and 1963. The first was carried out jointly with a French mission led by Egyptologist Jean Vercoutter. But from the second year, it was the Argentinian team and its Sudanese partners that took on the responsibility of excavating the temple and the surrounding settlements and cemeteries.

“Rosenvasser was foundational for Egyptological studies in Latin America, because this was the first time that a Latin American Egyptologist was commissioned to undertake such an endeavour,” Alejandro Parada, director of the Library of the Academia Argentina de Letras, where Rosenvasser’s library is kept today, told Middle East Eye.

“In a sense, it put on the international scene that, in this southern cone of Latin America, in countries that sometimes seem to be falling off the map, there was a very important construction of academic Egyptological thought,” he added.

To reach the Aksha settlement, Rosenvasser and his team first had to cross the 11,000 km from Buenos Aires to Khartoum, Preve’s documentary shows. And once they were in the Sudanese capital, they had to take a small plane to Wadi Halfa, in the far north of the country, and finally a car to drive another 50km across the desert.

“If you look at it, we are exactly 180 degrees off longitude, we are at the world’s maximum opposite. Imagine what it must have been in 1961 to fly from Buenos Aires to Wadi Halfa,” Preve said.

“And in fact, Rosenvasser’s journey is even more incredible, because it starts in Carlos Casares, which is 300km from Buenos Aires.”

In addition to Rosenvasser, who was in charge of the works and reading and interpreting the hieroglyphs, the Argentinian mission included a different architect and an archaeologist each year, so a total of five Argentinians ended up working at the site.

Feher said her father was also assisted by some 40 Sudanese workers, as well as foremen, boatmen to cross the Nile and home service, with whom he had a close relationship.

The members of the Argentinian mission lived during the season in modest adobe houses they rented from local people, with a roof made of palm leaves and no exterior windows.

Working days were intense for Rosenvasser, first in the excavation and, once the sun had set, recording all the inscriptions his team had found and transcribing them in detail in his notebook. However, he always found time in the morning to drink his mate, a traditional South American caffeine drink, the documentary recalls.

“He would get up very early, work before breakfast, then go back to the excavations, then take a very long nap and then back to work in the afternoon,” said Feher, who went to visit her father and mother, Pauline de Rosenvasser, in Aksha during the first season. Feher was going through a turbulent emotional time, after divorcing her first husband.

“There in the dunes, we talked about the heart. My father would clean the stones with his paintbrush while I told him about my love affairs,” she smiled. “It was all an immense adventure, but it had its logic, it didn’t come out of nowhere.”

From Nubia to La Plata

By the end of its expedition, in 1963, the Argentinian mission had been able to save 1,200 pieces from Aksha, Preve said. Of these, the best-preserved half remained in Sudan and is now in the National Museum of Sudan, in Khartoum, as shown in his documentary.

The other half, as stipulated by Unesco, was divided between the Argentinians and the French, who helped at the beginning of the works. And Preve believes that the part taken by France is now in the city of Lille, although he does not know whether it can be visited.

In fact, Rosenvasser’s original plan was to move and rebuild the Temple of Aksha on a higher site in Nubia, as was done with Abu Simbel. Yet technical difficulties and the condition of the temple made this impossible, according to the booklet of the La Plata museum.

So, the 300 or so pieces donated by the government of Sudan to Argentina found their way to La Plata, whose university covered part of the costs of Rosenvasser’s mission, together with the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (Conicet).

To get there, the pieces had to be taken from Aksha to Wadi Halfa, and then to Port Sudan, in the east of the country. From there they were shipped to London and then all the way to Buenos Aires, as the documentary shows. Feher said the pieces were moved from Wadi Halfa to Port Sudan by train, bypassing Khartoum.

The collection now in the Museum of La Plata includes more than 40 sandstone blocks with reliefs and inscriptions from the time of the Pharaoh Ramesses II, and many pieces unearthed during excavations, especially ceramics of different types and periods.

In addition to these relics, there is a smaller collection consisting of two coffins with their respective mummies and a number of figures and amulets.

These objects were acquired in 1888 from Cairo’s Boulaq Museum, today’s Egyptian Museum, by the former governor of the province of Buenos Aires and founder of La Plata, Dardo Rocha. It is believed that it was also Rocha who acquired the Buenos Aires papyrus deciphered by Rosenvasser.

Preve noted that since the fateful fire at the National Museum of Brazil in 2020, during which millions of objects, including hundreds from ancient Egypt, were lost, the collection in La Plata has become even more important.

'Rosenvasser was passionate about anything that had to do with Egyptology. And he kept working until he passed away'

- Elba Perla Fuscaldo, student of Abraham Rosenvasser

“The collection that Rosenvasser brought to La Plata is the only place in Latin America where history students can see some of this,” he said. “And due to sad circumstances, the value of this cultural heritage has increased even more.”

In addition to the collection at the museum in La Plata, Rosenvasser also donated his library, including his books on ancient Egypt and the Middle East, to the Academia Argentina de las Letras, thus extending his legacy.

“In the 1990s and early 2000s, 22 percent of those who came to the library consulted his collection. So, this collection helped to form the new generation of Egyptologists and specialists in Oriental studies,” said Parada, the library director. “It was crucial because he laid the foundations of Egyptology in Argentina.”

One of Rosenvasser’s first students and disciples, Fuscaldo, also ended up working on archaeological sites in Egypt between 1993 and 2007, becoming one of the first to do fieldwork in the region since Rosenvasser travelled to Aksha.

“Rosenvasser was passionate about anything that had to do with Egyptology. And he kept working until he passed away,” she said.

In Sudan, Preve noted, those most interested in the country’s history and the world of archaeology still remember today that without Rosenvasser the Aksha temple and the artefacts he helped rescue would remain 130 metres underwater, consumed by Lake Nasser.

“I was really moved that from a country like mine, with so many problems that we have, someone had the courage to do this,” he concluded.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.