Outback mosques: The cameleers who brought Islam to Australia

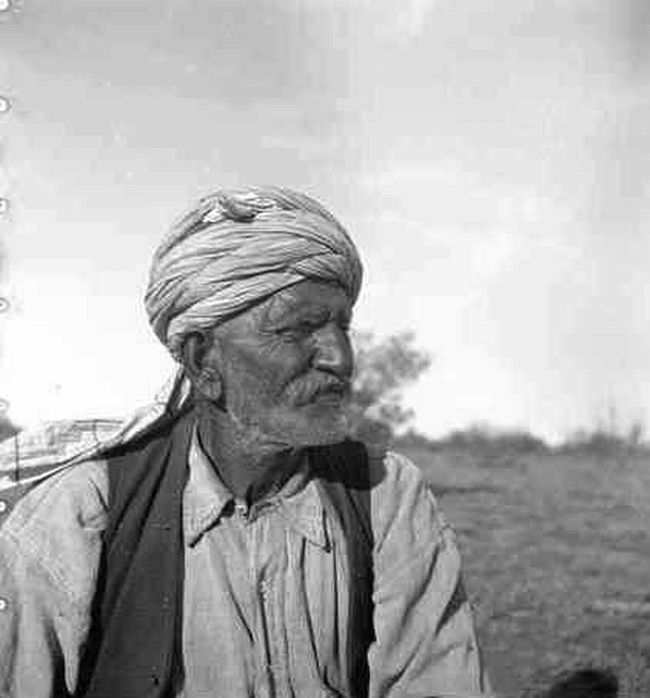

“My proper name is Amminnullah,” says the 81-year-old caretaker of Australia’s longest-standing mosque. “I stuck 'Robert' on there when I worked in the mines and shearing sheds, where no one could get my name right.”

Amminnullah “Bobby” Shamroze oversees the Mosque Museum of Broken Hill, a remote Australian mining city of 17,000 people with a rich, albeit little-known, Islamic history.

Built in 1887, Bobby’s mosque is the oldest-standing mosque in Australia. It was founded by the so-called “Afghan cameleers”, the catch-all-term used to describe 2,000-4,000 camel drivers who came to Australia from the early 1800s from modern-day Pakistan, India and Afghanistan, bringing Australia’s first major wave of Islam with them.

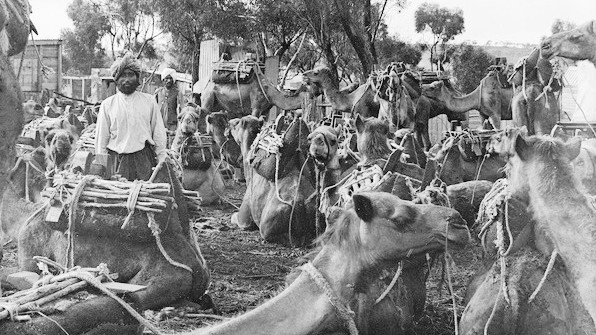

They arrived after the European settlers travelling to gold mines in Australia’s red, rugged centre realised they needed a new way to transport supplies.

Because of the soft sand and heat, horses wouldn’t get the job done, so the decision was made to import camels. But once the camels arrived in Australia, the settlers realised they didn’t have the experience to control them. They needed experts.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Afghan camel drivers

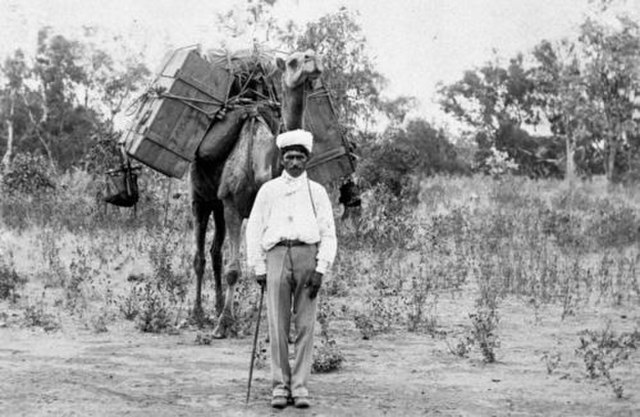

Enter the Afghan camel drivers, who soon began arriving by sea at bustling ports like Fremantle, Port Pirie and Port Augusta. Between 1860 and 1930, around 20,000 camels were shipped to Australia. Of the three camel drivers who were the first to arrive in 1860, two were Muslim (the other was Hindu).

The cameleers would carry supplies to settlers working the gold mines of central Australia, guiding expeditions between remote cattle and sheep stations, and identifying water sources for travellers. They would also set up supply depots along the way, sometimes erecting mosques next to small creeks or lagoons.

This gruelling work was essential to the development of Australian railways and mining industry.

Temperatures in the Australian outback are surprisingly varied, averaging up to 38C in the summer months and regularly getting below freezing during winter nights. The cameleers would be away for months at a time, leaving their children to be looked after by their wives, who were often local women.

Traces of the cameleers are felt throughout modern Australia, both in major cities like Adelaide, where they founded the Central Adelaide Mosque, and more remote, regional centres like Broken Hill.

The Ghan, Australia’s famous 3,000-km railway line running between the northern and southern coasts, takes its name from the Afghan cameleers.

Like that train line, previously dubbed the The Afghan Express, the cameleers traversed Australia’s toughest terrain.

“It must’ve been pretty hard work,” Bobby says. “They used to drop off water around the trees in big steel containers. When they came back, they knew where the water was.”

Bobby, who has a wife and three daughters, is a direct descendant of the cameleers once famous in Broken Hill, and one of the last of his generation. Bobby’s father, Shamroze Khan, and maternal grandfather, Zaidullah Faizullah, were both successful cameleers, and prayed at the mosque Bobby now oversees.

Having spent the last 30 years researching the cameleers, he’s become the descendants’ best-known spokesperson, leading tours of the mosque and giving occasional interviews to interested TV stations.

Much of his research is done by digging through family photographs and speaking with relatives, something he took an interest in after being repeatedly approached for information by curious outsiders and Muslims passing through town.

He’s helped uncover a chapter of Australian history that includes the country’s first waves of Islam.

Most of the cameleers who arrived in Australia were practising Sunni Muslims, and set up the country’s first mosques, many of which were built hundreds of kilometres from major centres.

Building a community

They built the first, the Marree Mosque, as early as 1861 and it is situated almost 600km from Adelaide, the closest major city. It no longer exists on its original site.

Today, the location of the mosque remains hazy, however some believe it was taken apart in the 1950s. A replica of it was later built for tourists in Marree, although not in the exact location of the original.

'We’ll get buried the same way the old Afghan blokes were buried, and my mum and dad. I’ve got my plot out there, and my wife has hers'

- Amminnullah 'Bobby' Shamroze

Bobby’s grandfather, who died in 1962, was the Broken Hill mosque’s last practising mullah, but neither he nor Bobby’s father taught the youngsters their mother tongue, Urdu, which Bobby would hear as they sat around the campfire together at nights. They also didn’t pass on their faith or religious customs.

“The trouble was that we were too young and they were busy,” Bobby says. “We just got on with the Australian way of life.”

But Broken Hill’s early Muslims did teach Bobby how to conduct Islamic funerals. He helped bury his grandfather and will ensure his and his wife’s burials follow Islamic customs.

“We’ve got our own section in our cemetery,” he says. “We’ll get buried the same way the old Afghan blokes were buried, and my mum and dad. I’ve got my plot out there, and my wife has hers.”

In the early 1900s, there were around 400 cameleers living in Broken Hill. They lived across two camps located on the northern and western outskirts of town. Each camp had a mosque, but only the northern mosque, where Bobby is caretaker, remains intact.

The northern mosque functions mostly as a museum today, so Broken Hill’s roughly 15 Muslim families pray at the Almiraj Sufi & Islamic Study Centre, which opened in 2013. It features a prayer room, library and study areas, a large bookshop and - since 2019 - a Sufi bakery.

Led by Murshid FA Ali ElSenossi, a Libyan who arrived in Australia in the 1990s, the study centre’s founders were drawn to Broken Hill by the chance to reinvigorate the spiritual legacy started by the cameleers almost 200 years ago.

“Islam says water is symbolic of knowledge,” Dr Abu Bakr Sirajuddin Cook, a research fellow at the study centre, tells MEE. “Where better to have a spring of water than in the desert?”

Today, Broken Hill’s Muslim population fluctuates, due to the city’s status as a destination for thousands of fly-in, fly-out workers employed in the nearby lead and zinc mines. (A little-known fact is that BHP, the world’s largest mining company, stands for Broken Hill Proprietary.)

Other temporary workers include police officers and trainee health workers who undertake residencies in Broken Hill, some of whom come to pray at the centre.

Spiritual legacy

In addition to occasionally leading prayers and giving the Friday khutbah at the study centre, Dr Cook researches Australia’s wider Islamic history.

Until now, little research on the cameleers and earlier Muslim visitors to Australia, such as the Makassan traders from modern-day Indonesia, has been done through a Muslim lens, something Dr Cook is addressing.

By reading archival newspaper reports about the cameleers, he is able to use his knowledge of Islam to interpret customs the European settlers didn’t understand at the time.

“One of the newspaper articles talks about the cameleers shouting at the top of their voices,” he says. “It’s possible that this is the earliest documented example of a circle of dhikr [a Sufi custom] in Australia.”

Less easy is tracing the cameleers’ journey from the subcontinent to their arrival at the ports of Australia. Migration to Australia was heavily controlled at the time, but documents like departure and arrival cards are in languages like Urdu, Farsi, Arabic and English, meaning researchers need to be multilingual.

“We have all those records in places like Port Augusta and Fremantle, but accessing them is tough,” Dr Cook explains.

Many cameleers returned to their home countries after years working in Australia, as discriminatory immigration laws forbade them from naturalising. But others started families with locals. Intermarriages with Aboriginal women were especially common.

“Because the cameleers came from a predominately tribal culture, there was a mutual recognition with indigenous Australians,” Dr Cook says. “There’s also talk of white women embracing Islam and going on Hajj.”

As the railways and roadways the cameleers helped build began connecting more of Australia, the need for the camels and their drivers lessened. Many cameleers, like Bobby Shamroze’s father, started working in the mines.

Others found work on the sheep and cattle stations they previously supplied with food and water.

“The last camel team that I know of finished in 1929,” Bobby says. “That was Sultan Aziz. He took the last load from Broken Hill up to a place called Durham Downs. He was 79 years old then.”

Almost 100 years later, the history of cameleers like Sultan Aziz, Zaidullah Faizullah and Shamroze Khan is preserved in mosques, murals and statues around Australia, small reminders of an under-appreciated chapter of Australian history.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.