From Osiris to Ammut: How Ancient Egyptian death rituals carry a timeless message

In the Egypt and Sudan department of the British Museum stands an artefact which belongs to a member of an elite, literate class encompassing an infinitesimal number of ancient Egyptians.

The document is the Papyrus of Ani.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Ani was a royal scribe who lived in Luxor, formerly known as Thebes, the city of the god Ammon, during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses II in around BCE 1250. And the papyrus was Ani's passport to the afterlife.

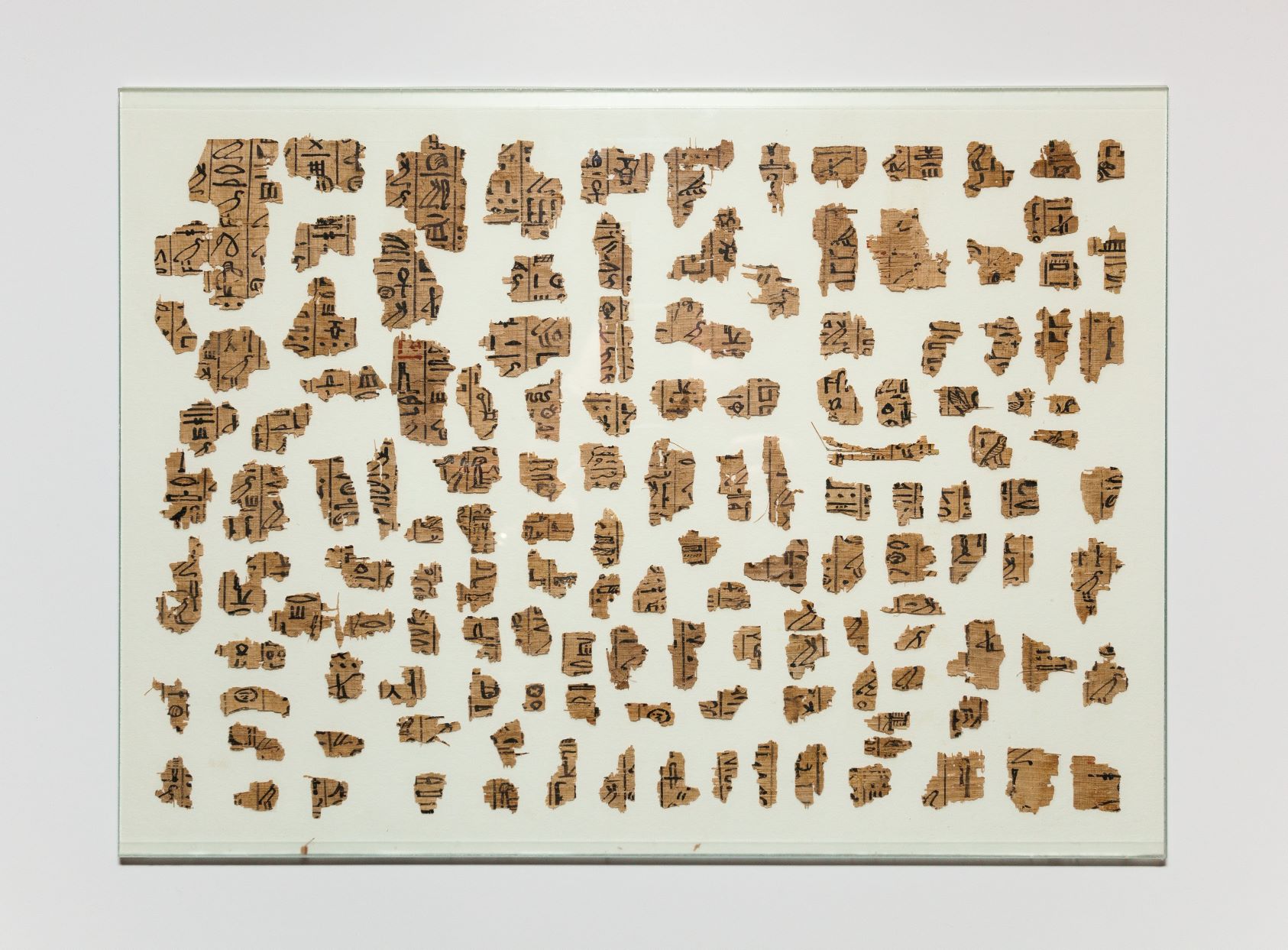

The relic is one of the finest extant samples from what is known as the “Book of the Dead”, a loosely reconstituted corpus of upwards of 250 spells.

Never fully codified by ancient Egyptians themselves, the compendium gathers oral tradition and materials from pyramids and coffins written up to 4,000 years ago. Accompanying the dead in their journey to the afterlife, the spells are of varying lengths and unique to their commissioner. They tell us about ancient Egyptian beliefs and contain an enduring and universal message.

Of the 44 objects the British Museum lists as belonging to the tomb of Ani, none are quite as mesmerising as the vibrant and evocative scrolls, retrieved – or, more aptly, trafficked – via Egyptian intermediaries and the debonair 19th-century British Egyptologist Ernest Wallis Budge. As is the case with many objects found in western museums, deceit was involved in their procurement.

Budge misled the Luxor police chief and the (French) director of the Service of Antiquities, the latter responsible for overseeing excavations and endorsing foreign archaeological missions, by having local associates discreetly bury his “acquisitions” outside, at night-time, near the house where he stayed. Later, he removed the artefacts from Luxor to London, where they please crowds trickling between desecrated mummies and stone tablets at the British Museum.

The British explorer proudly offered scabrous details of his feat in his colourful memoir, and with the release of its first English-language edition in 1899 which presents the scrolls, he is credited for having popularised the version we now identify as the Book of the Dead.

Before Budge, German archaeologist Karl Richard Lepsius coined the term, “borrowing” from the way local Egyptians described the texts. That colloquial influence on the name suggests that Egyptian Arabs broadly knew about their provenance and perhaps meaning.

The original name of the spells (The Book of Coming Forth by Day) suggests the incantations were intended to help complete the owner's journey to the afterlife by sunrise.

Life in the next world

At the core of the vignettes and incantations is a wish for the dead to seek immortality and peace. The dead need guidance, preparation and reassurances, and this is the reason why inscriptions typically stayed close to the coffin and body of the deceased. The Book of the Dead tells of tales which are unknown to human, empirical experience. It imagines the afterlife as a place, and a moment to reap reward as well as punishment.

Two figures appear prominently in its illustrations – Osiris (the embodied figure of resurrection) and Anubis (the embalmer). In mythology, Osiris and his wife Isis ruled over Egypt before his jealous brother Set murdered and dismembered him. Faithful Isis looked for the remains of her husband, then pieced him together and a posthumous child was born – Horus.

Horus eventually came of age and avenged his father by killing his uncle Set, then seizing control of Egypt, with Osiris remaining king of the underworld. Osiris’ parabolic fate conveys an idea about the cycle of death, crystallised in justice and an existence beyond mortal life, which ancient Egyptians thought they would symbolically re-enact in death.

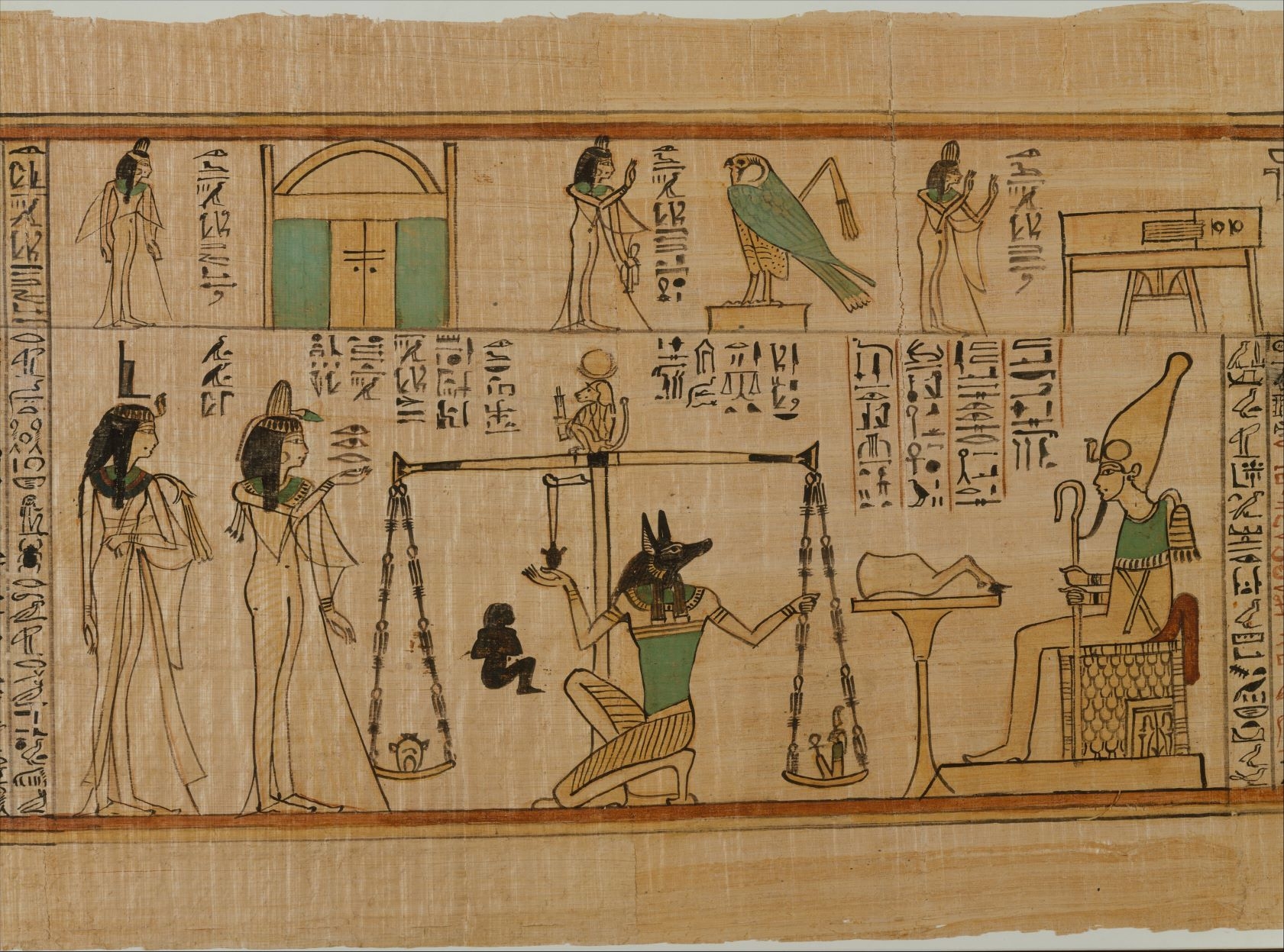

Together with Osiris, Anubis, the canine-headed god of embalming and protector of tombs and mummies, guides the dead. For instance, Anubis features in one of the most memorable scenes of the Book of the Dead: the weighing of the heart. This ceremony, which is part of the “judgment of Osiris”, was a central rite of passage. The heart of the deceased would be placed on a scale against a symbolic feather: the lighter the heart, the closest to “Ma-at”, or the divine incarnation of justice. Characterised as female, Ma-at was understood as a form of order, peace, harmony, or “cosmos”, as opposed to “chaos”.

The ceremony fundamentally questions whether the dead lead a good life. The heart is a muscle and it is also a memory of moral conduct. Hearts were traditionally left in the bodies of mummies, as opposed to decaying viscera. Ancient Egyptians believed the heart contained an essence and human intelligence, what we in the modern era may refer to as consciousness, or associate with our brains.

Judging the dead

Prior to the weighing of the heart, the dead would enter the Hall of Judgment, or Hall of Truth, where one was expected to declare his or her innocence against a list of vices and through a “negative confession” to Osiris, 42 assessors and other divinities.

As evidenced by the relic held by the British Museum, Ani would have negatively confessed to stealing, killing, engaging in blasphemy and violating other ethical codes, starting with the words: "I have not committed."

The judgment established a common understanding of right and wrong, which could vary according to the deceased’s occupation in life.

Mirroring traditional forms of adjudication, the projected outcome is one of a conciliatory, near-forgiving nature, although an unjust heart could be eaten by the half-crocodile creature called Ammut and the deceased’s soul – composed of nine parts – could also be prevented from reaching higher levels of paradise. On Ani’s scrolls, Ammut lurks close by.

Life deeds, then, counted in death, an event which remained disorientating for ancient Egyptians. The Book of the Dead communicates a map of foreknowledge, a compass, a “cheat-sheet” of passwords to help towards this transition and remember the ladders. The deceased was not expected to fool the gods with low-level trickeries; instead, specific amulets and texts near the body would figuratively whisper where to go, what to say, and how to address divinities in cases of forgetfulness. Family and friends left behind would provide the necessary sacrifices to sustain the soul of the departed in their journey.

What permeates through the Book of the Dead is movement, a flow which carries the dead from one step – from one test – to another until they reach a union with the sun, the god Ra, the life-giving warmth.

Shifting away from the ‘colonial gaze’

In the Metropolitan Museum in New York, one can admire the funerary golden sandals of a Pharaoh’s wife from the 15th century BCE, an object recalling the hope of “standing” again, which explains the preservation of the body and what qualifies its sanctity. A coffin was envisaged as a waiting room until a meeting with Osiris’ court was possible, until the dead could join the sun, a celestial realm, and not die again.

The scrolls, like mummies, pyramids and other emblems of ancient Egyptian culture, have often played into western exoticism, if not fetishism. How we choose to represent and interpret ancient beliefs influences the way we convey and value heritage.

Youssef Rakha, author of Barra and Zaman, which critically reviews Shadi Abdel Salam’s 1969 movie The Mummy, considers the legacy of the Book of the Dead as “residual” to contemporary Egyptian society. In a July 2021 conversation with this writer, he said that there is a “survival of these texts in the Old Testament, in Egyptian proverbs, in traditional musical forms such as mawwal”. Rakha proposes to shift the paradigm when examining ancient Egyptian culture, to “emancipate ourselves” from the induced simulacra of the colonial gaze.

Digitalisation initiatives, such as the Totenbuch-Projekt at the University of Bonn in Germany, offer a possibility of a deeper understanding, by comparing different sources and attempting to reunite papyri fragments dispersed around the world. Remnants from the Book of the Dead are not anodyne art pieces to be collected and glorified under the aesthetics and pretence of 19th-century imperial booty; these artefacts were sacred to a culture, and constituted the final wishes and dignity of a deceased.

And while they constituted part of the sacred, for the ancients, they continue to hold relevance today.

At first, images of jackals, owls and crocodiles may seem quite removed from the daily occurrence of modern life. Yet, myths speak about timelessness. They speak in a universal language and of values, and once deciphered they possess a self-evident and comforting truth that protects against human fear and suffering. The Book of the Dead reminds us of transience, the consuming and inevitable flow of nature, and that what matters for later is to live well in the present.

When did ancient Egyptians stop believing in their stories? The Book of the Dead progressively fell out of use towards the end of the Ptolemaic era, when Rome defeated Queen Cleopatra and annexed Egypt as a Roman province in 30 BCE. Foy Scalf, from the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, recalls in Book of the Dead: Becoming God in Ancient Egypt that other texts became popular, before various forms of religious syncretism and “the sweeping Christianization of the third and fourth centuries” overtook indigenous funerary practices.

We don’t know if scribe Ani completed his passage towards Ra and the sun’s solace, and we can still only guess what the largely poor and illiterate mass of ancient Egyptians could afford in terms of rites, amulets and other preparations. Yet all, rich and poor, presumably prayed for one life-affirming longing: not to get lost in darkness.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.