From cassettes to streaming: Moroccan classics are getting a new life online

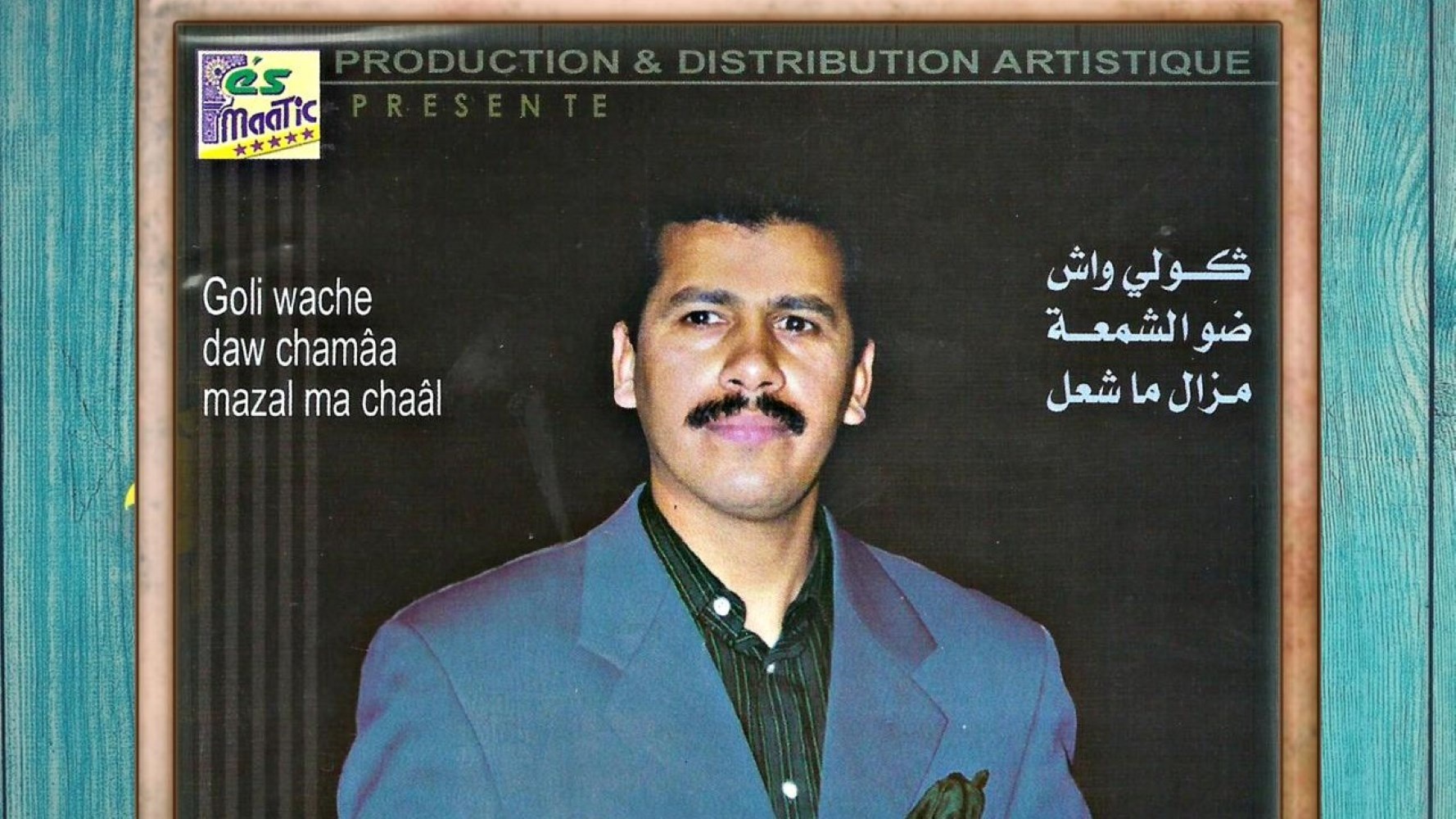

On Friday and Saturday nights, traffic spikes on Imad Tazi's YouTube channel. His record label, Fes Maatic, is a leading hub for Moroccan music online, hosting a collection of more than 1,200 songs originally released on CD and cassette.

Listeners hail from across the world, concentrated in countries like France, Spain, the United States and, of course, Morocco.

As the sun sets where they are, they open YouTube on their phones and laptops, crank up the volume and blast music from decades past.

The songs they stream, like the upbeat El Ghaba by the chaabi singer Lahcen Laaroussi, have been hits for decades, perennial favourites played at weddings, clubs and house parties ever since they were first released.

Others stayed relatively unknown for years, given new life by fans online, an interest perhaps sparked by a viral TikTok video.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Streamed from YouTube, Spotify or somewhere else, the tunes inspire impromptu dance sessions in homes, car singalongs and commutes to work, capturing the very best of Moroccan music.

"That song by Lahcen Laaroussi was released in 2004," says Fes Maatic's Imad Tazi, speaking to Middle East Eye over the phone from Fes.

"Even now, I hear it at nightclubs, and it always gets a great reaction. People are still dancing to it after 20 years."

For most people, in Morocco or abroad, hearing songs like El Ghaba is only possible online.

Up until a few years ago, Moroccans could easily buy CDs and cassettes in souks (markets) across the country. Now, even speciality music shops are rare, making physical copies difficult to track down.

For most people, this leaves the internet as the only way to listen to music from decades past. But as anyone who has tried and failed to find a half-forgotten favourite on Spotify or YouTube knows, plenty of great music hasn't yet made it online.

When it comes to Moroccan music, a handful of platforms are filling those gaps. Along with Fes Maatic, they include YouTube channels Sawt Al Hilal and EasyDis, plus fan-run websites like Moroccan Tapes and Moroccan Tape Stash.

The people behind the platforms have their own reasons for maintaining them, be it passion, business or the simple desire to spread their favourite music as wide as possible.

For Fes Maatic's Imad, it's a family business. His father, Hammadi Tazi, started Fes Maatic in 2000 after running another classic label, Fassiphone, with two friends.

A legendary label in its own right, much of Fassiphone’s catalogue still remains offline.

"My father used to bring artists to our house to record albums," Imad remembers, calling his father “the encyclopaedia of Moroccan music”.

Following a stint living in Canada, Imad returned to Fes in 2010, where he's worked for Fes Maatic ever since.

Beginning with YouTube years ago, Imad has uploaded a small fraction of the countless songs Fes Maatic released during its 14 years of operation.

The 1,200-plus already online have been played more than 70 million times on YouTube alone.

Without his efforts, this music would remain on CDs and cassette tapes gathering dust in cupboards and garages around Morocco.

Even if some tunes were uploaded as unauthorised, low-quality uploads, the collection would not be centralised like it is on Fes Maatic, where albums can be heard from start to finish.

The choice to go digital

Imad is able to put so much of Fes Maatic's catalogue online thanks to a forward-thinking decision his father made more than 20 years ago.

"Fes Maatic was the first company to integrate digital recording into the Moroccan music scene," Imad says. "Before that, it used to be all analogue."

Recording digitally keeps music permanently accessible, long after it was recorded. Though digital recording methods have been around since the 1980s, many labels in Morocco and elsewhere stuck with analogue methods well into the 2000s, preferring analogue's warmer sound profile, along with the reliability that comes from recording to a physical medium.

Outside of a flood or fire, analogue tapes are relatively robust, unlike digital files that can be corrupted or deleted.

With the sound and reliability of analogue recording, however, comes a downside: decades later, expensive, highly specialised equipment is needed to get the music from the tapes.

Storing the tapes also requires physical space. In the 1980s, a single 45-minute album would be recorded to analogue tape stretching across thousands of metres, stored on a handful of circular tape reels.

For a label like Fes Maatic, which released over 1,000 albums with at least six songs each, storing its entire catalogue on analogue tape would require a huge storage space.

Today, 24 years after it released its first music, Fes Maatic's catalogue remains at Imad’s fingertips on hard drives and CDs, able to be quickly accessed with a computer and remastered before being put online.

Not every label had the foresight – or luck – to record and store their catalogues digitally.

The master recordings for thousands of Moroccan albums from other labels lie on ageing tapes, stored away in dusty warehouses and storage sheds.

To track down copies of specific CDs or cassettes, listeners would need to go through resellers on websites like Discogs, where they sell as collector's items for many times the original price.

Plenty of listeners, little income

Moroccan music blasts out of taxis, cafes and corner stores throughout the country. But, buying the music itself is difficult.

Musicians are paid for performances, passing around hats for tips for performances at restaurants, getting tips from wedding guests, but rarely sell, say, CDs to crowds.

And when you do find a music store, perhaps tucked away on a quiet Casablanca side-street, they'll often sell pirated copies of the CDs, meaning the labels or musicians behind them won't get a cut.

'Today there are more listeners, more platforms, more views. The problem is you don't get what you deserve'

- Imad Tazi, Fes Maatic

Record labels around the world face such problems. Even if, like Fes Maatic, they are popular online, income from streaming websites like Spotify and YouTube is minimal, paying a fraction of a cent each time a song is streamed.

This leads to a certain irony. Thanks to the internet, Fes Maatic's reaches more people than ever, touching listeners around the world. Yet because they don't sell CDs or tapes anymore, its income is just a fraction of what it used to be.

Where the former powerhouse label supported multiple families throughout the 00s, its total income is now only enough to support Imad alone.

"Today there are more listeners, more platforms, more views," says Imad.

"The problem is you don't get what you deserve. You hear your music on the radio, in coffee shops, everywhere. But you don't get anything from it.”

The power of cassettes

Morocco's musical landscape is amongst the richest in the world. With a population of roughly 38 million, the country has developed countless musical genres and regional sub-genres.

The best-known style outside Morocco is gnawa, a hypnotic, spiritual type of trance music.

Its musicians are some of Morocco's most famous outside the country and include Mahmoud Guinia, who collaborated with the jazz saxophonist Pharoah Sanders on a now-classic album, The Trance of Seven Colors.

Inside Morocco is a seemingly endless patchwork of musical variants. Beloved styles include chaabi, malhun and reggada, along with countless regional sub-genres, such as ahwash, izlan and Rif music.

The music spreads across the country's many languages, mostly in the Moroccan Arabic dialect Darija, but also in the native Amazigh languages Shilha, Tarifit and Tamazight.

Getting to know the ins and outs of the country's landscape is, for many fans, a lifelong quest. Even Moroccans who have spent years immersed in music have the potential to stumble upon a style they've never heard before.

"I recently found a type of music from the Zagora area, southeast of Marrakech," said Amino Belyamani, who runs the website Moroccan Tapes.

"They use square bendirs (a circular Moroccan hand-drum) and dance with swords. I'd never seen that before. So it's not only new artists I'm discovering, but whole genres of traditional music. It's endless."

In addition to professional operations like Fes Maatic, there's an undercurrent of hobbyists and super-fans who curate their own collections of music online, such as Belyamani.

He’s uploaded more than 65 tapes of Moroccan music to his website since December 2019, along with artwork and whatever information he can find about each release.

There's music from Mahmoud Guinia, the titan of gnawa, plus beloved Amazigh singers like Mohamed Rouicha and Najib Medaghri.

With each upload, Belyamani shares information about the release and artist, such as how the ahwash singer Moulay Ali Chouhad used to compete in "poetic jousting sessions" as a child, shaping his future talent for improvisation.

Or how the lyrics to a chaabi song from Morocco's north translate to: "They [the authorities] caught him smuggling hashish."

A cassette needs to meet certain criteria before Belyamani uploads it to Moroccan Tapes.

"Firstly, the album has to be good," he says. "The tape also can't be too deteriorated. And it needs to have an interesting backstory.

“Maybe it has a unique rhythm, for example. Moroccan music is so rich in rhythm, so if I find one that is rarely used, I need to post it."

Belyamani is an ambassador for Moroccan music online and abroad, performing in the gnawa group Innov Gnawa, sharing Moroccan music on the internet, and hosting Moroccan musicians for concerts in New York, where he’s lived since 2009.

Born and raised in Casablanca, Morocco's largest city, Belyamani moved abroad not long after finishing high school, studying jazz and classical in France and the US

Having grown up playing classical piano, he only became fascinated with Moroccan music after leaving the country.

An obsession with gnawa was the gateway to genres like chaabi and ahwash, and at the end of each visit home, Belyamani would fly out with a suitcase full of new CDs, bought in markets of Casablanca or the outskirts of Agadir. He eventually turned to cassettes, realising so much of his favourite music remained on this medium alone.

"I started buying cassette tapes because I'd find these albums that I couldn't find on CD, whether it's gnawa or Amazigh music," he says. "I now have friends who send me boxes of tapes. In fact, I'm looking at a box full of them now."

There's never been a better time to be a fan of Moroccan music. Whether listening from the suburbs of Agadir or apartment blocks in Düsseldorf, decades of sounds are easily available.

Thanks to hobbyists like Amino Belyamani and music industry figures like Fes Maatic's Imad Tazi, these online collections are expanding, giving new life to the songs that soundtracked weddings, birthday parties and festivals for decades.

The flipside to all of this is that the efforts of former powerhouses like Fes Maatic struggle to be financially viable, and resemble a public service more than the thriving businesses they once were.

As these labels continue to spread their presence online, perhaps they will find fans who need more than YouTube or Spotify streams, even willing to pay to have their favourite classic album on CD or cassette, bought directly from the label.

Until then, a world of Moroccan music is available a few clicks away.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.