How Chris Morris took down the FBI's fake plots with terror comedy

Chris Morris went to Miami’s Liberty City neighbourhood because he’d heard a lie in a London pub.

In 2006, Morris had watched Alberto R Gonzales, the US attorney general, on TV behind the bar, his every word imbued with the slick authority of the news media that the British satirist parodied so sharply during The Day Today, his revered 1990s BBC TV series.

Gonzales was announcing the arrest of an underground “army” that had been ready to launch a ground war on the US from inside its own borders. This was, Gonzales told TV reporters, clearly a massive plot, and thwarting it had saved many lives.

It later came to light that this was a fanciful fiction cooked up by the FBI. Morris didn’t know it then, but this case would, along with hundreds of others like it, provide him with the framework and the inspiration for his second feature.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

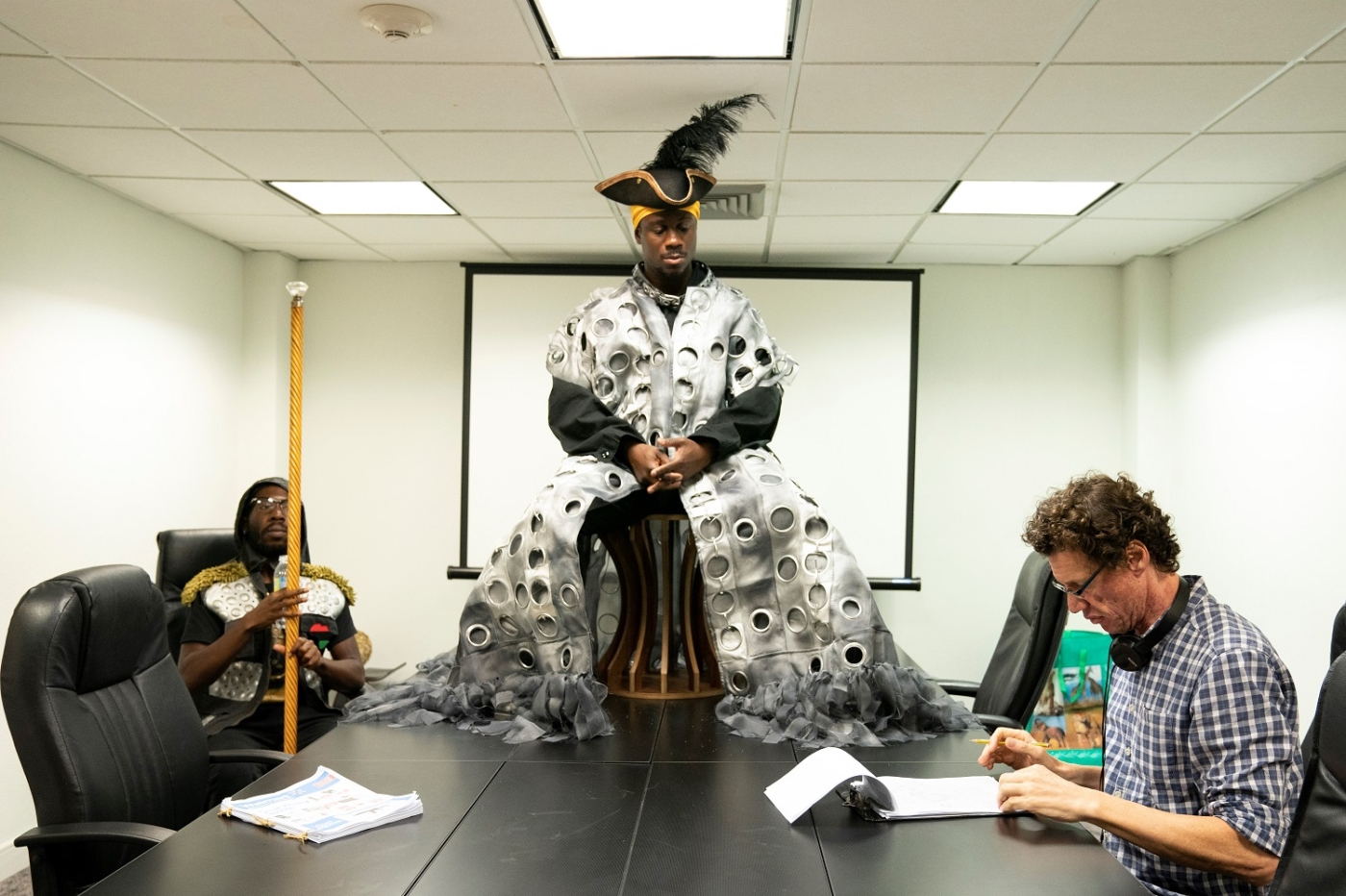

The Day Shall Come, which is released in UK cinemas this week, tells of Moses, a black, working-class sometime preacher and would-be revolutionary, who is offered a way out of his and his community’s troubles by FBI informants, posing as conduits to wealthy Middle Eastern sponsors of terrorism.

It’s been almost 10 years in the works, amid a wealth of research and investigation and, Morris admits, a significant number of re-writes. "You would call it fake news, before fake news was invented," Morris told the audience at its London premiere.

Or, to use Human Rights Watch’s description of the way in which the FBI has used undercover informants since 9/11, it’s about how the US government has “created terrorists out of law-abiding individuals by conducting sting operations that facilitated or invented the target’s willingness to act.”

When sci-fi becomes fact

The Liberty City Seven, as they became known, were a group of poor men on the fringes of society, just trying to get by when a couple of FBI informants came along with promises of untold riches - if they would pledge allegiance to Al-Qaeda and launch an attack on US soil.

Some wild suggestions followed. The group said they could blow up the FBI’s Miami headquarters. Or they could create a tsunami that would wipe out Chicago by toppling the Sears Tower.

Their ringleader, a former preacher called Narseal Batiste, bluffed and blustered, saying he could get 5,000 soldiers to start a holy war. He held a meeting in a fishing tent in a bid to seem impressive. After three trials, Batiste and four others were handed prison sentences of between seven and 13 years.

That was in 2009. All five men have since been released. Batiste is now a painter living in Houston, Texas.

But the case set a precedent: it was an example of what the FBI called – in words that could have been lifted from Philip K Dick’s short story Minority Report – “pre-emptive prosecution”, in which alleged terrorists are arrested before they’ve done anything.

Trevor Aaronson - who Morris met with while researching A Day Shall Come - reported in his book The Terror Factory that the FBI and Justice Department indicted and convicted more than 150 people after sting operations involving alleged connections to international terrorism in the 10 years following 9/11.

To date, more than 300 defendants have been prosecuted through such operations, in which an informant not only encourages a suspect to plot an attack but also gives them the necessary financing and equipment.

Lawyer Martin Stolar, who defended a young Pakistani-American who made wild claims about blowing up a New York City subway station, told Aaronson that the FBI is “creating crimes to solve crimes so they can claim victory in the war on terror”.

The absurdity of threat

We are in Chris Morris territory here: the absurdity, the stupidity, the hysteria, the manufacturing of a threat where none really existed and, crucially, the underlying sense that this is totally wrong. The result is The Day Shall Come.

The character of Moses, as played by Marchant Davis, is loosely based on Narcille Batiste. He has a wife and a young daughter. They’re facing eviction from their house, which also acts as a church where he and his followers (they number in the single digits) praise “Allah, Melchizedek, Jesus, black Santa, Mohammed, and General Toussaint”.

He prays for divine intervention to bring down “the cranes of the gentrifiers”, which are pushing his community even further out of what little they have. His group believes that it can summon the dinosaurs with a trumpet and that the dinosaurs will help them overthrow white supremacy. Moses’s most profound wish is for a horse, who he can then talk to.

Things are just as unusual over at the FBI’s Miami headquarters, in which Anna Kendrick’s ambitious young officer squabbles with her boss and colleagues over exactly how much reality they can manufacture. They fire toy guns at each other in their office - a detail Morris says comes straight from real life (an FBI employee told him that the fiercest battles took place between agents working on Shia terrorism and those working on Sunni terrorism).

The Day Shall Come shows the FBI as both cruel and hapless, struggling even to manipulate the powerless in their bid to appear to be defending the homeland.

In the film, as in real life, the bureau’s handling of its informants is crude. The actor Kayvan Novak, who was also in Morris’s first film Four Lions, says he’d been hearing from Morris about his new character for at least five years. The character turned out to be an “Iranian paedophile”, whose sexual crimes are easily used against him by Kendrick’s FBI agent and becomes one of the informants who sets out to frame Moses.

In the end, this is a comedy that turns out to be deadly serious. At the premiere in London, an audience member asked the cast if they registered the difference between the surreal and the real. Both Davis and Novak reacted with bemusement, perhaps because as actors it’s not their job to signal those kinds of distinctions.

Instead Morris picked up the question, pointing out that when the FBI is obtaining convictions for a range of absurd, manufactured cases, there is no longer a line between the real and the surreal. What is real - the FBI accepting broken speakers as payment for grenades, a mentally ill homeless man being given $40 by the bureau so he could buy a machete so they could then arrest him - is also surreal.

Morris described what the victims of these stings go through as a “Truman Show existence”. It’s hard to think of a better description for the kind of manufactured reality in which these people find themselves.

Bomb dogs and helium spokesmen

In the UK especially, Morris is revered as a maker of brilliant, era-defining satire. Why Bother?, his 1999 BBC Radio series with Peter Cook, remains a high point of surrealist British comedy. Morris’s TV series The Day Today, Brass Eye, Jam and Nathan Barley, made during the 1990s and the 2000s, perfectly parodied a media and popular culture mired in absurd stupidity and hypocrisy.

His first film, Four Lions (2010), did the same thing for homegrown British terrorism, although it could be argued that his The Day Today bomb dogs sketch - in which explosive-laden dogs roamed UK streets - was his first direct foray into the hysteria that exists around the idea of terrorism.

It aired in 1994, when the British public chiefly regarded terrorists as members of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). Morris also lampooned the UK government's ban on members of Sinn Fein, the group's political wing, speaking on TV by forcing them to inhale helium between each sentence.

In Morris’s earlier work, pathos and a sense of injustice about what was happening in the world weren’t really the point. The comedy came first: the absurdity and the satire carried weight but they didn’t really carry a weight that suggested an urgent need for the world to change, although underneath it all, there was a sense of pure frustration about existing somewhere so stupid and cruel.

FBI counter-terrorism documents have referred to the Prophet Muhammad as a 'cult leader'

InThe Day Shall Come, Morris is engaging directly and deeply with injustice. Moses and his family are poor outsiders, bulldozed by capitalist America and turned into criminals by its vehicles of power. In the land of big dreams, Moses dreams big, not quite realising that his face and his thoughts don’t fit in a society that finds it far easier to lock away racial minorities and the working class than it does to help them.

This can be seen most obviously with America’s Muslim population and with terrorist threats perceived to come from the Middle East. FBI counter-terrorism documents have referred to the Prophet Muhammad as a “cult leader”. They have said that “mainstream” American Muslims are likely to be terrorist sympathisers. They have reported charitable giving among Muslims as “a funding mechanism for combat”.

Morris was quick to point out at the film’s London premiere that what the FBI has been doing began under President George W Bush, accelerated under Barack Obama and is still in place under Donald Trump.

This demonising of powerless minorities in the name of the “war on terror” has been a bi-partisan project and its legacy can be seen in the Islamophobia that is rife in the United States today.

The difference between comedy and tragedy is that with comedy you get a second chance. When Marchant Davis’s stepfather first saw the film, he knew immediately that things wouldn’t end well for the poor, black protagonist.

The final punch, when it comes, is hard to take. In this comedy, as in real life, there are no second chances at the end of the road.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.