Can Iraq beat the drought and become the breadbasket of the Middle East again?

The area of land in the south of Iraq between the mighty Tigris and Euphrates rivers – a region renowned for its rich alluvial soils and, for thousands of years, one of the most fertile agricultural areas on Earth - is drying up. Many farmers are leaving the area.

Last summer there was rioting in Basra and elsewhere in the south over a chronic lack of drinkable water and growing sewage problems.

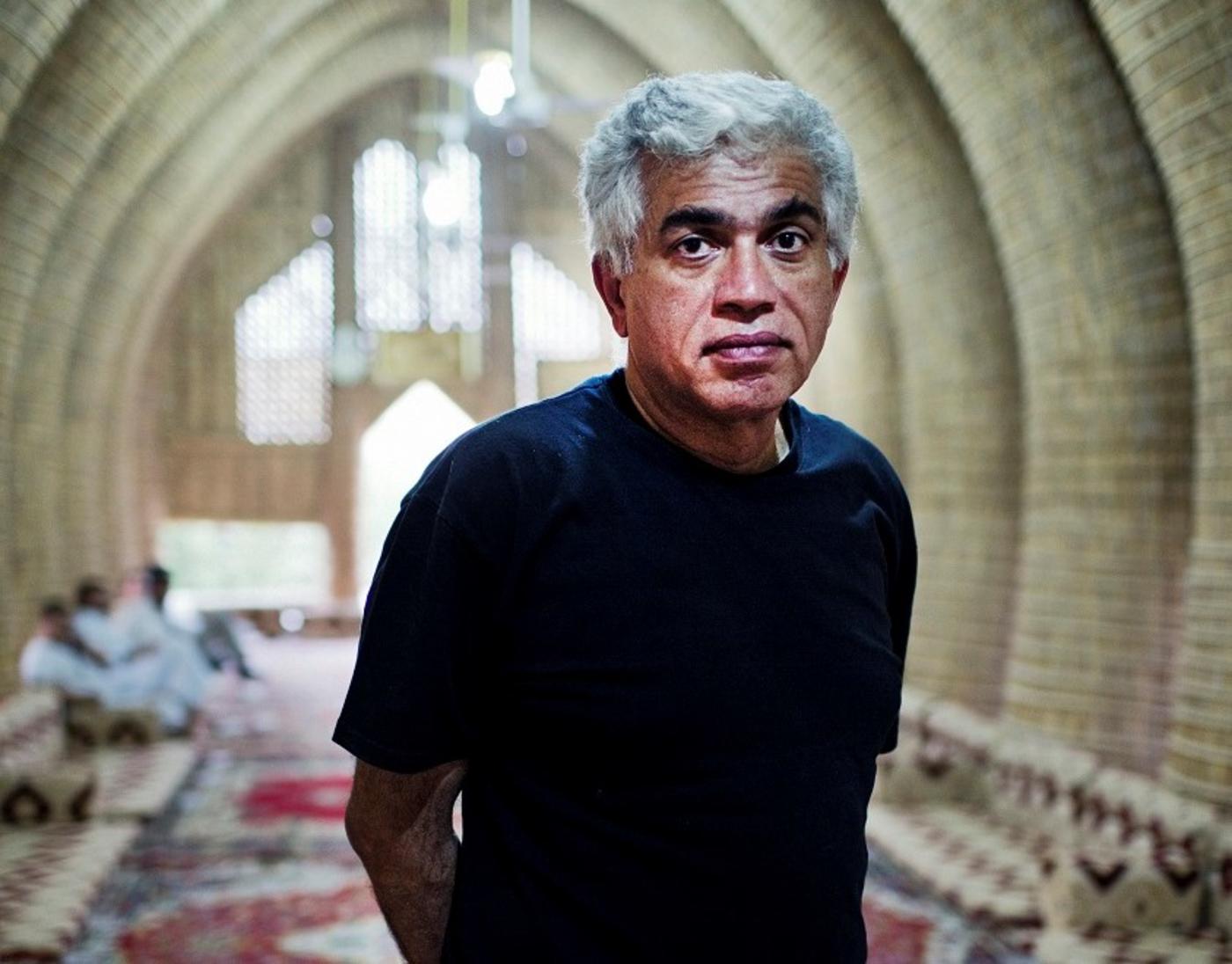

Yet amid this environmental meltdown, Azzam Alwash - conservationist, civil engineer and one of the leading figures in Iraq’s fledgeling ecological movement – remains optimistic.

“People don’t give nature enough credit for how resilient it is,” says Alwash. “With the right policies, Iraq could manage its water supplies and become, as in ancient times, the breadbasket of the Middle East.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Alwash, 60, was born in Nasiriyah, in south-eastern Iraq. As a child, he recalls paddling a small boat through southern Iraq’s marshes with his father, an irrigation engineer.

“It was a piece of heaven, full of fish and birds, water buffalo grazing on land amongst the reeds.”

The return of life

In the late 1970s, Alwash went to California, studied for an engineering doctorate and built up a successful career as a civil engineer. He married, had two daughters and, for a while, lived the American dream.

“I learned my optimism in the US,” says Alwash. “A ‘can do’ attitude was injected into me and has stayed despite all the setbacks and problems encountered over the years.”

In the mid-1990s, Saddam Hussein launched his brutal campaign against the Shia of the south, bombing, draining and poisoning large areas of Alwash’s beloved marshes.

Following Saddam’s downfall in 2003, Alwash - after more than 20 years of living and working in California - returned to Iraq. He founded the Nature Iraq environmental group and put his hydraulic engineering skills to work, becoming one of the prime movers behind the re-flooding of the marshes region.

“The local people - part of the ancient Sumerian culture - did much of the work themselves, puncturing the dykes and bringing back the water to a large section of the marshes,” says Alwash.

“It was wonderful to see life in all its rich biodiversity returning.”

In recognition of his conservation work, Alwash was awarded the prestigious Goldman environmental prize in 2013.

In 2016, the marshes were listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, with the area being described as “unique, one of the world’s largest inland delta systems in an extremely hot and arid environment”.

Threats looming

But the marshes – along with hundreds of thousands of acres of once fertile farmland in southern Iraq – are once again under threat.

Changes in climate are affecting the whole area: the summer of 2018 was one of the hottest and driest on record in the region. The government was forced to impose a ban on growing water-hungry crops such as rice and wheat, while soils and water courses became increasingly salt ridden.

Many water storage systems and canals were destroyed during Iraq’s wars. Lack of investment in infrastructure, corruption and a stifling bureaucracy have also added to the region’s problems.

Water shortages have been exacerbated by a large-scale programme of dam building on the upper reaches of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and their tributaries in Turkey, Iran and in Iraqi Kurdistan over the years.

There is a particular concern in Iraq about the impact of the massive Ilisu dam project on the Tigris in south-eastern Turkey, which is just coming on stream.

“In the old times, waters flowing down the Euphrates and Tigris would produce an annual flood in southern Iraq,” says Alwash.

“The floods would bring silt to replenish the land and they’d also wash away the salt that had accumulated due to evaporation.

“This yearly pattern in water flows was a miracle of nature, sustaining 8,000 years of agriculture. Floodwaters also fed into the marshes, encouraging the reeds to grow, the fish to spawn, the birds to nest.

“It’s just not dam building and climate change that have caused the damage. Years ago canals were built to allow shipping to navigate up the Euphrates; salt intruded from the sea.

“It’s all resulted in this annual pulse of water down the Euphrates and Tigris being removed."

Is the answer oil for water?

So does the ever-optimistic Alwash have any answers to what seems to be a full-blown environmental crisis?

He says the only remedy for Iraq’s water problems is a wide-ranging arrangement with neighbouring countries – in particular, Turkey.

'That the Turks have control of the Euphrates and Tigris is a fact'

- Azzam Alwash, conservationist

“That the Turks have control of the Euphrates and Tigris is a fact. There’s no getting away from it. So why not aim for some form of cross-border water federation?"

Alwash says Iraq loses billions of cubic metres of water each year due to evaporation. Turkey’s reservoirs – in deep and often shaded valleys - are much more suited for storing water than those in Iraq.

“We could do a trade with Turkey: it would give us water and we would supply it with oil and gas. Some people might call me a dreamer but what’s the alternative? More conflict over water?

“Iraqis are tired of fighting. They are becoming a lot more aware of the wider issues. Our population is growing fast. We have to produce more food.

“Like sensible people anywhere, Iraqis just want to get on with their lives – and be at peace.”

Not only does Alwash believe Iraq’s agriculture can be revived, but he also says the country could be turned into a solar energy powerhouse.

“On average we (in Iraq) have 340 days of sunshine per year – more than three times as much as European Union countries. Think [about] what we could do if we harnessed all that energy. We could supply solar power to Turkey, even to eastern Europe.”

The only time Alwash’s generally positive outlook seems to dim is when mention is made of the Mosul dam – Iraq’s biggest such facility, built on the Tigris and controlling water supplies to millions, including residents of Baghdad.

There has long been concern that the dam - a Saddam Hussein sanctioned mega project constructed in the early 1980s and built on soft, porous soils - is inherently unsafe.

A European Commission report in 2016 simulated a collapse that would produce a wave at least 12 metres high that would reach Mosul in an hour and 40 minutes. In one scenario, floodwaters would impact six million people, with two million threatened by two-metre-high waves and 270,000 within the radius of 10-metre waves that would destroy everything in its path.

In the past, Alwash has likened the dam to a nuclear bomb with an unpredictable fuse.

In order to plug holes and caverns opening up below the dam’s surface, a constant programme of grouting has to be carried out at Mosul.

“The grouting work is impossible – you cannot fill all the spaces that open up,” says Alwash.

“At the moment, due to the rains and substantial water that flows down the Tigris, Mosul is about three-quarters full. It should not be that much: the situation is dire.”

It seems that even for the ever-optimistic Alwash, there are some problems which appear insurmountable.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.