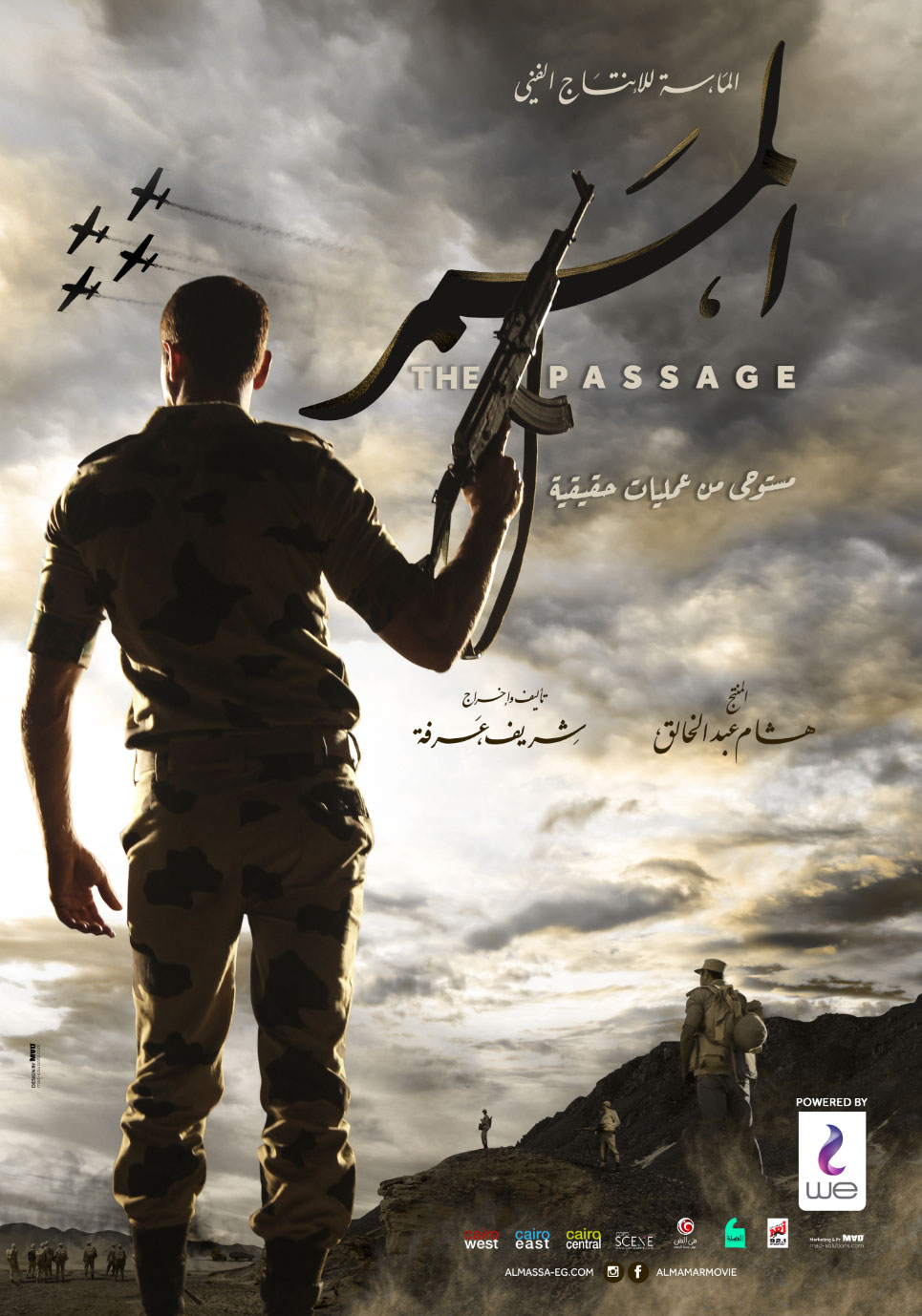

Egypt's biggest film: How The Passage owes a debt to Sisi

In one of the many telling scenes in Sherif Arafa’s The Passage (El Mamar), the loving wife of an army lieutenant compares Egypt’s 1967 military defeat against Israel to a nightmare, a real nightmare which her husband and hundreds of other Egyptian soldiers were forced to endure. Like any bad dream, she tells him, it’s bound to end. He’ll wake from it with new-found energy that will propel him to victory.

This blatant dictum could have easily been lifted verbatim from the numberless rousing speeches of Egyptian president Abdel Fattah El-Sisi. It only lacks any description of the current nightmarish climate in Egypt.

Indeed, The Passage closely resembles a Sisi speech. It is stirring, simplistic and overwhelmingly sentimental; a gung-ho, testosterone testament to the resilience of the Egyptian man, and a call to arms for national unity against the enemy, whatever (or whoever) it may be.

It’s also one of the most barefaced pieces of propaganda Egyptian cinema has made this century.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Produced by mega-producer Hisham Abdel-Khalek of prominent production house El Massa, The Passage cost nearly LE100 mil (nearly $6 mil), making it the most expensive Egyptian feature ever.

Its popularity is undeniable: box-office revenues have surpassed LE30 mil (nearly $2 mil) in less than two weeks. Its success has been interpreted by some government’s supporters as approval for the current administration, a forceful charge of patriotism designed to ignite the populace’s love for the nation.

The national football team was shown the film last week. A pro-government party offered 6,000 free tickets (free transport) for residents of the working-class Cairo neighbourhood of El Gamaleya. A horde took to Twitter to celebrate the day when the film topped the charts for the first time.

It must be stressed that the appeal of The Passage is not limited to one side of Egypt’s political divide. People need popular entertainment to escape their reality, and The Passage is no different. It is an easily digestible spectacle with a reductive worldview, designed to re-instil national pride lost amid the storm of social injustice, agonising inflation, disregard for human rights and the diminishment of freedom of expression.

1967: Defeat and disillusion

Egypt’s defeat in the 1967 war and subsequent victory in 1973 have inspired a handful of films down the decades that commemorate the bravery of the army while exploring the downbeat mood preceding the retrieval of Sinai. The most enduring works of the period, such as Adrift on The Nile (1971), El Karnak (1975) and The Sparrow (1972), were set outside the battlefield. As such they are old, acidic stories displaying the disillusionment with the reign of then-president President Gamel Abdel Nasser and the end of the 1952 revolutionary dream.

It is a sentiment that The Passage barely approaches.

The film commences in early summer 1967, a few days before the start of the conflict, in a country which is generally tranquil, if somewhat tense. With Nasser making incessant threats, Israel orchestrates a military attack that takes Egypt by surprise.

Early on, Arafa attests that the Nasser administration decides not to retaliate, although the army is organised enough to hold its ground.

This theory is mainly drawn from The 67 Officers Speak Out by Essam Deraz, a 1989 book which collected testimonials of the soldiers on the ground and is widely regarded as one of the most accurate records of what happened.

The Passage thus depicts the war as less a clear-cut defeat, and more an institutional failure. It’s the sole political line Arafa takes in a film that is essentially a combat picture peppered with a few stale expository sequences of the soldiers and officers’ myriad dreary domestic lives. All soldiers, without exception, are benevolent, kindhearted, god-fearing men whose initial despair towards defeat is soon replaced by steely determination to restore the occupied lands and conquer the blood-thirsty Israeli aggressor.

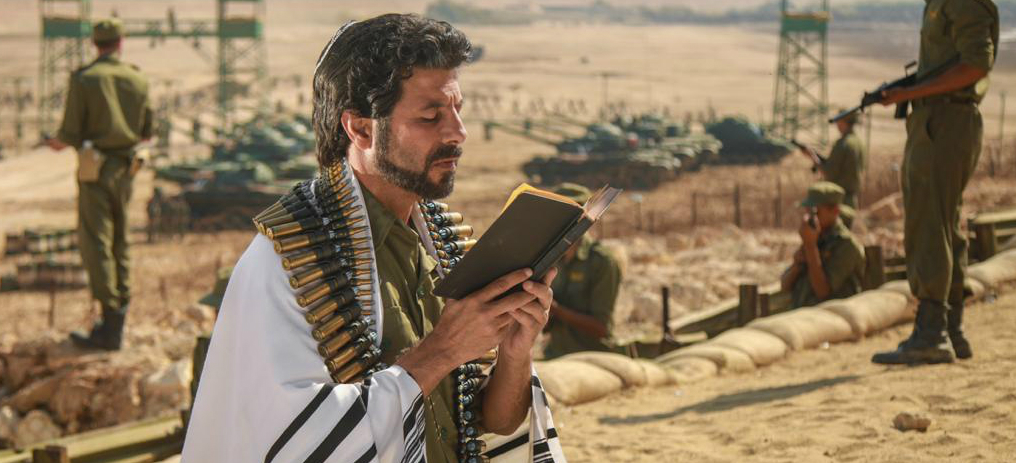

The Israelis, in comparison, are seen as a sadistic horde, hellbent not merely on protecting the land they snatched, but also on destroying by all means possible their Egyptian enemy.

An Israeli sniper during the surprise attack on Sinai enjoys shooting random Egyptian soldiers from his helicopter with a smirk on his face. This is only the prelude to the arrival of Israeli lieutenant David (Jordanian Eyad Nassar), the film’s main antagonist, who shares his compatriots’ mercilessness and mendacity.

David kills his Egyptian prisoners of war on impulse, relishes in torture and casually breaks the Geneva Convention. He constantly reminds his Egyptian counterparts that they have lost the war to the great Israel army; that Israel is entitled to the land that God has promised them; and that nothing shall stop Israel from maintaining its military dominance over the region. He is, in short, the typical cartoonish Israeli villain who has populated endless Egyptian dramas during the past half century.

Like all propaganda, this is very black-and-white stuff, without a scintilla of moral or political complexity, nor without any depth or pathos.

The comic relief is carried by Ihsan (Ahmed Rizk) as a war correspondent who, prior to documenting the efforts of the troops, gets a conscientious awakening when he is hired by two belly dancers as their publicist.

Big explosions, lifeless shootouts

Subtlety is not a characteristic of Egyptian mainstream cinema, and The Passage is no exception. It is not just how the film draws a thick line between the good and the bad, but also in the ham-fisted, tacky back stories of the soldiers, and the excessive reliance on Omar Khairat’s over-emotive score.

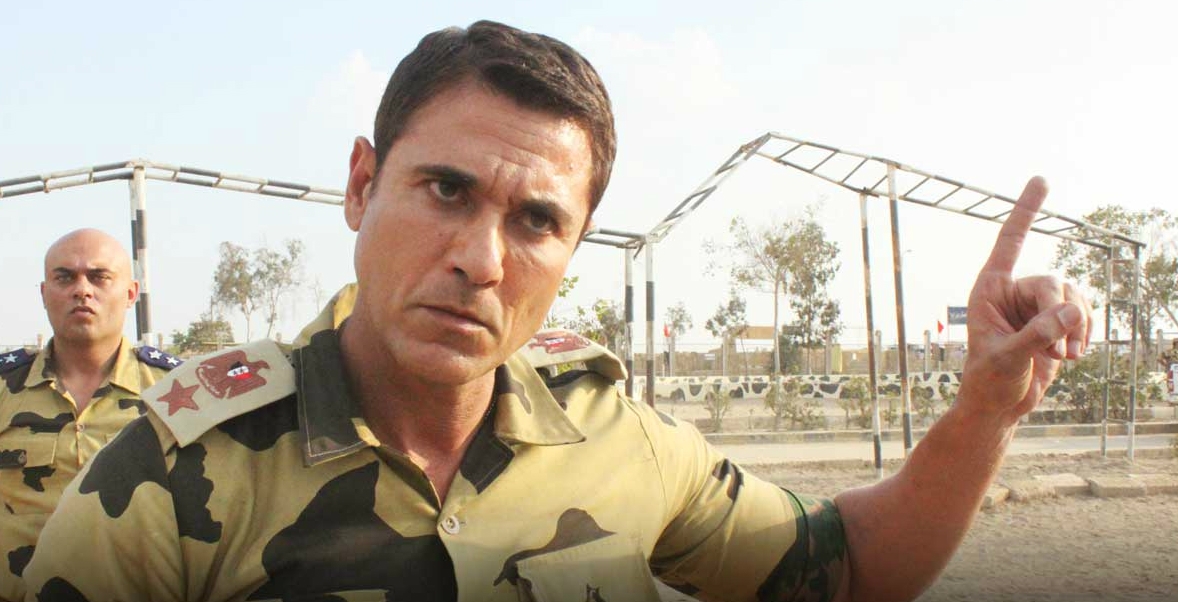

The soldiers are divided into two categories: the tormented buffed-up guys such as Nour (Ahmed Ezz) and Ahmed (Mohamed Al-Sharnoubi), a young engineer, who try to spare their significant others the agony of sticking by their side because “they’re not the same men they used to be”.

Then there are the under-represented minorities such as Hilal (Mohamed Farag), an Upper Egyptian; Abou Regieba (Amir Salah), an estranged Nubian; and Amer(Mohamed Gomaa), a loyal Bedouin. They all forgive their enfranchisement because, as Nour puts it time and time again, all Egyptians are one.

But nonetheless, Arafa’s desire for a wide range of representation couldn’t find room for a single proper Coptic character. The sole Christian soldier in The Passage appears for five seconds at an outdoor movie screening.

Even the action sequences fail to truly impress. The best war films are distinguished for their ability to full capture the horrors of wars (Apocalypse Now; Come and See); for the insights they provide of the elusive human nature (The Thin Red Line; The Grand Illusion); or for their sheer aesthetic invention (Lebanon; The Battle of Algiers). The Passage, by comparison, flounders on all fronts, mistaking extensive production values for superior film-making.

Arafa’s direction lost any stability once he embraced videogame aesthetics at the beginning of the century - all hand-held camera work and unjustified zooms, irritatingly going in and out of focus. His action sequences suffer from the same artificiality, lacking spatial coherence and any urgent sense of propulsion. It’s all big explosions and lifeless shootouts - and feels all the more mechanical and dehumanising for it.

The Passage and the media landscape

It is also interesting to note how The Passage fits into the government’s current relationship with the wider media. Much has been written about the monopolisation and consolidation of Egypt’s TV industry by companies connected to the administration.

For example Synergy, which is owned by Eagle Capital for Investment, belongs to an unnamed sovereign governmental body. Not only did it and its parent company produce nearly all of this year’s Ramadan serials, they also own channels themselves. The result was what most TV critics dubbed as the worst Egyptian season of the century: a drab series of crime dramas and humorless comedies with little relation to the current Egyptian reality.

There are also the growing number of censorship associations – including the higher council of media and the drama committee – which tightly control content in a fashion not seen since the heyday of Nasser.

Thousands of technicians have lost their jobs as production levels drop to more than half in comparison to previous recent years. Even ardent supporters of the government have objected to this sweeping control, which has become the worst-kept secret in the business.

Because of its enormously lavish resources and revenues, TV was the last contested media domain between an administration adamant about reforming the content and production of the industry; and an industry that admiringly continued to break both aesthetic and social boundaries, especially when it came ro drama, with every passing year.

Now look at cinema. It was a battle lost to the government long ago. Despite the notable growth in the box-office revenues during the past few years – boosted primarily by higher ticket prices, in turn boosted by the staggering inflation – the resources of film-makers are limited compared to TV. Films are also subject to even tighter censorship, which restrict filmmakers’ engagement with any contested facet of the social or political reality.

The result is that cinemas are flooded with nothing but diverting (and occasionally well-made) comedies and action features where the police and the military are always depicted in a flattering light (the army did not directly invest in The Passage, yet it supplied the production with all required equipment and personnel).

Sisi’s attention to TV and cinema has also been extensively documented: his much-discussed 2017 speech in which he insisted the government must play an active role in regulating entertainment while “instilling positive values” in their content is now regarded as changing the face of the industry.

Few, however, excepted it to be that blunt, or that crass.

Why did Arafa make The Passage now?

The Passage is a natural fit for Arafa, a highly acclaimed and hugely successful film-maker who rose to fame during the 1990s with landmark political satires written by Waheed Hamid and starring Adel Imam, the Arab world’s biggest comedy star.

During the past two decades he has also directed action features and biopics, many of which were infused with naive nationalism rather than any perceptive exploration of identity and nationhood. The Passage is Arafa’s first credit as a writer (he co-authored with poet Amir Taema) and, as such, does not feel out of place in his oeuvre.

It’s almost impossible not to read The Passage as a Sisi manifesto, containing every principle he’s advocated since he came to power

But its timing couldn’t be more than coincidence. Any film is a product of its age, no matter how fanciful it may be - so why make it now?

Last year, Sisi referenced the 1967 defeat in another speech, stressing that “the battle is far from over”. The enemy was clearer then, he said, but now it is more ambiguous and multifaceted. Once again, he emphasised the crucial role media and art must play in raising awareness and enchasing the intellect of the people.

In that sense, it’s almost impossible not to read The Passage as a Sisi manifesto, containing every principle he’s been advocating since he came to power in 2014.

There are the religious, if not overly religious, middle-class family values which govern the relationships between the soldiers and their partners and families; the self-sacrificing and forgoing of differences for the greater good of the country; and the scientific thinking, self-belief and determination needed to achieve collective goals, whatever they may be.

Most obvious and problematic of all is the portrayal of belly dancers as agents of national and moral corruption. In The Passage they are used as a symbol of the debased and depraved art that Sisi constantly attacks in his speeches and attributes for tearing apart the nation’s wholesome moral fabric. Bad art prospers in times of crises, the dancers say in one scene, drugging the public from facing the gravity of the problems at hand.

Ironically, the same can be said of The Passage, a film designed first and foremost to stir fading patriotism at a time of unprecedented economic depression by using an oversimplified narrative and distasteful sentiment. Oddly enough, it arrives as Egypt is strengthening its ties with Israel with El-Sisi himself admitting in his infamous CBS interview that Israelis have been allowed to carry out airstrikes against terrorists in Sinai.

The difference between real art and the harmful entertainment which Sisi has vehemently criticised is that the former stimulates people to re-examine their realities; to demystify the myths created by the media, politics and capitalist powers.

In contrast, the latter manipulates the masses into submission, maintaining the status quo by offering them quick and cheap emotional gratifications.

It’s not difficult to guess to which group The Passage belongs.

- The Passage is currently on wide release in Egypt and the Gulf region.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.