Five relics Egypt wants back from foreign museums

For decades Egypt has been demanding the return of its historic artefacts, many of which are today spread across the world in museums from Switzerland to the USA.

While the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in Cairo houses more than 120,000 artefacts from ancient Egypt, those held in museums outside of the country have often been acquired illegally, according to experts and activists.

Egyptians are not the only ones trying to retrieve their treasures from foreign museums. The Elgin Marbles at the British Museum are regarded as one of the world's most contested treasures, with the Greeks making numerous demands for their return.

However, Egyptian officials have managed to secure the return of some items, including a 2,100-year-old coffin that was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, but many others remain dotted around the world.

For those demanding a return, making sure Egyptian artefacts remain in the country redresses the country's exploitation during the colonial period when some foreign archaeologists unfairly appropriated thousands of relics.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Returning artefacts will also strengthen Egypt's tourism industry, which relies heavily on its ancient past.

Here, Middle East Eye looks at some of the items Egypt wants back.

1. The Rosetta Stone, The British Museum, London

Egyptian officials have renewed demands for the Rosetta Stone to be returned from where it is currently based in the British Museum in the heart of London.

The stone was discovered in the Nile Delta city of Rasheed, or Rosetta in English. Napoleonic troops found the relic in 1799 while constructing a fort during the brief French occupation of Egypt.

Over the centuries, the stone has come to be known as one of the world's most renowned historical artefacts and was crucial in helping to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The 2,200-year-old granite stone is engraved with hieroglyphs, Ancient Greek, and demotic script, which is a cursive form of Egyptian hieroglyphics.

With the presence of Ancient Greek text, a language that was widely known during the period it was found, linguists like the 19th century Frenchman Jean-Francois Champollion, were able to decipher what the ancient Egyptian symbols meant.

This new understanding of the inscriptions paved the way for scholars to translate other ancient Egyptian texts and helped unravel some of the mysteries of this civilisation.

After the French invasion of Egypt failed in 1801, Britain acquired the tablet and has held it for more than two centuries.

Zahi Hawass, the former Egyptian antiquities minister and an archaeologist, has reiterated calls for the stone to be returned, stating that he would launch an international petition.

“The Rosetta Stone is the icon of Egyptian identity,” Hawass said. “The British Museum has no right to show this artefact to the public,” he added.

But with thousands of people visiting the British Museum every year to view the stone, it is not likely Egypt will have it back any time soon.

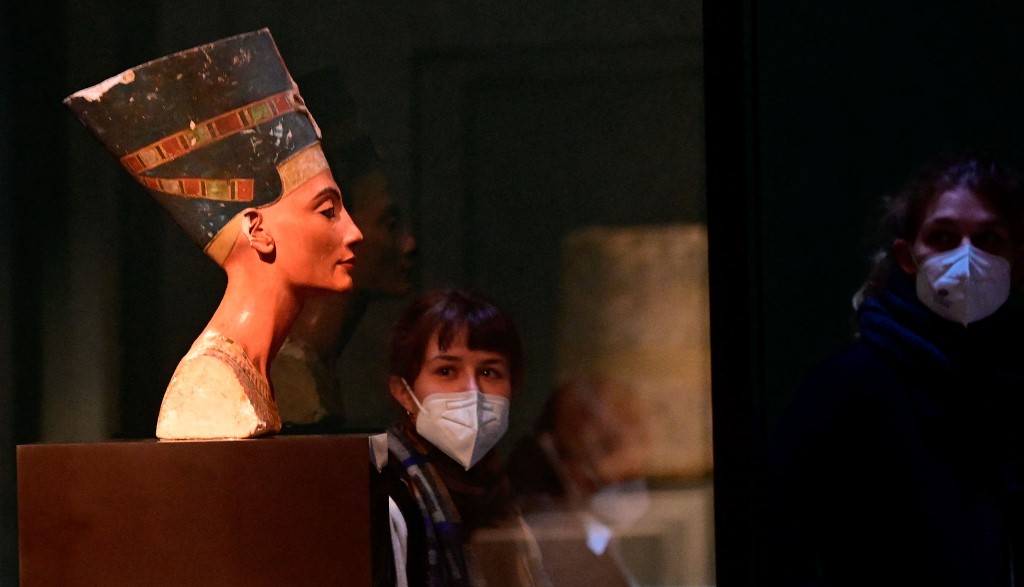

2. Bust of Queen Nefertiti, The Neues Museum, Berlin

Another artefact at the top of Egypt's list of relics it wants back is the bust of Queen Nefertiti, which currently resides in the German capital of Berlin.

The statue of Nefertiti, designed by the sculptor Thutmose, was discovered in December 1912 by a German archaeologist named Ludwig Borchardt in the Minya region of Upper Egypt, and is remarkably well preserved, with its colours still intact.

Dating back to 1340 BCE, during the New Kingdom dynasty, the bust is made of limestone, crystal, gypsum, and wax. Although little is known about the queen, her statue is regarded as one of the most beautiful and important Egyptian artefacts. She is often depicted as a regal and powerful character, matching that of her husband the Pharaoh Akhenaton.

Cairo says that Germany took the relic illegally and in contravention of rules on which archaeological finds can leave Egypt.

The rules state that exceptional artefacts found by excavation teams should be handed over to Egypt, while others can be distributed amongst the teams that discovered them, as well as Cairo’s Egyptian museum.

In 1946 Egypt’s King Farouk I sent a letter to the Allied Control Council of Germany asking for the return of the bust. Another official letter was sent in 2011 by the former secretary of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, Zahi Hawass.

Both were dismissed by Berlin. Germany insists its possession of the bust is legal and Egyptian demands for its return have not been successful.

3. Zodiac ceiling, The Louvre, Paris

Believed by some to be the world’s first horoscope, the Zodiac of Dendera is a square ceiling panel, dating back to around 50 BCE.

The panel was found in the Temple of Hathor in January 1799 by French troops. It details the movements of the stars and constellations. Also engraved into it are theories about the end of the world.

In addition, the panel also includes the 360 days of the Egyptian year and details about the deity that corresponded to each Zodiac sign.

The ceiling was taken from its original home around 25 miles north of Luxor to the Louvre museum in Paris in 1821.

In August of 2022, Zahi Hawass called for the return of the Zodiac Ceiling, alongside the bust of Queen Nefertiti and the Rosetta Stone.

In 2009, the Egyptian official cut ties with the Louvre, citing its refusal to return artefacts.

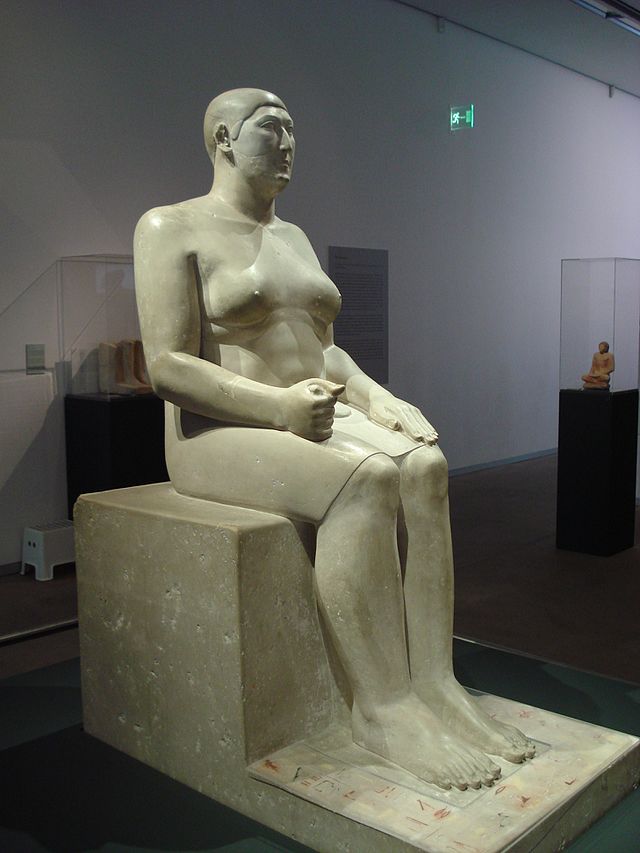

4. Statue of Hemiunu, Roemer-und-Pelizaeus Museum, Germany

This life-sized statue made from limestone was discovered in 1912 by archaeologist Hermann Junker of the German Oriental Company.

Hemiunu is believed to be a high-ranking official and the nephew of the Old Kingdom pharaoh, Khufu, who ruled around 4,500 years ago.

Believed to be a senior vizier, Hemiunu is associated with the building of Khufu's pyramid, more commonly known as the Great Pyramid.

Statues were believed to be a home for the deceased and a means to worship their image. While it was common during the period to portray subjects as they would look in the afterlife - a more flattering depiction generally - Hemiunu's depiction is considered to be closer to how he actually looked.

Researchers believe his full figure also represents his wealth and power.

Inscriptions on the statue's footplate - now housed at the Roemer-und-Pelizaeus Museum - describe him as a "master of the scribes of the king", "overseer of all works of the king" and "priest of the ram of Mendes".

According to Hawass, the teams that uncovered the artefacts in Egypt lied about the importance of their finds in an effort to deceive the authorities and justify taking the artefacts back to their home countries.

5. Bust of Prince Ankhhaf, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Bust of Prince Ankhhaf is made from limestone covered in a layer of plaster and possibly depicts the person responsible for the building of one of Giza’s pyramids and the carving of the Sphinx.

Discovered in 1925 by a Harvard University expedition, the relic eventually ended up at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

The discovery of the statue was a major breakthrough and it is considered to be one of the most important artefacts of the Egyptian Old Kingdom.

Ankhaf was associated with the royals of the Fourth Dynasty, and the red tone of the plaster covering the statue was typically used for the flesh of men. Although the exact date of the statue's production is unknown, it is believed that Ankhaf lived during the reign of Cheops.

Egypt’s requests for the statue to be returned home have been rebuffed more than once by Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts.

One of the main points of contention is that the bust of Ankhaf was given to the museum by a previous Egyptian government, meaning that the current government has no legal grounds to ask for it back.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.