Courting creativity: How indie troupes revived Egyptian theatre

Even before the enormously popular 1970s comedies of Adel Imam and Samir Ghanem, Egyptian theatre rested on a rich tradition. From the 1900s to the present day, the streets of downtown Cairo have been lined with theatres, even if their glory may not be as visible today as it once was.

Pioneer performers Naguib El-Rihani and Youssef Wahbi led some of the first commercially successful troupes of the 20th century.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Over time, their comic and dramatic experiments would give way to literary masterpieces by the likes of Tawfik al-Hakim and Yusuf Idris, which were in turn succeeded by televised classics such as The Kids Have Grown Up (El Eyal Kebret), The School of Misfits (Madraset El Moshaghibeen), and The Married Ones (El Motazawegoon).

For decades, the plays were regularly broadcast on mainstream Arab TV channels, becoming cultural staples of the first day of Eid, a ritual Netflix capitalised on by releasing a collection of them in time for Eid al-Fitr last year.

Today, many factors should be spelling the demise of Egyptian theatre. In a world increasingly dominated by streaming services, more and more directors, actors, and technicians are setting their sights on Netflix and the Arabic streaming service, Shahid, for career opportunities.

Also, the in-person cultural scene is still reeling from closures caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. But, even before the pandemic, iconic theatres had shut down and were either converted into cinemas or left standing abandoned for multiple reasons, including waning audience interest, insufficient funding to keep them all operational, and fire precautions brought in after a tragic fire at the Beni Suef Theatre in 2005.

The National Theatre itself was closed for six years after a fire in 2008, only reopening in 2014.

All but a handful of the theatres still open are owned by the government, and opportunities for independent artists outside the establishment - such as production grants and awards - are hard to come by.

Yet young Egyptian actors, directors, and playwrights continue to carve out enclaves of creativity on the same streets – if not always the same theatres – where pioneers of the genre first took their bows over a century ago.

A troupe in every room

Mohamed Metwally is a 31-year-old theatre director and actor, with a day job as a clapper loader on film and TV sets. Whenever there’s a gap in filming schedules, he can be found prepping, rehearsing, and staging plays in classical Arabic with his independent troupe, All In, like their 2018 adaptation of Egyptian playwright Salah Rateb’s absurdist drama, Al Samt (The Silence).

When I meet him, he’s holding rehearsals for his fourth show, in one of many studios in downtown Cairo that rent out rehearsal spaces by the hour. In a rundown but imposing mid-century building, we talk in a narrow hallway, waiting for Metwally’s room to free up.

'The independent scene is full of people. Walk into any rehearsal room, and there’s a troupe; I can barely book a slot'

- Mohamed Metwally, Egyptian theatre director and actor

Our conversation is punctuated by the diligent sounds of rehearsals from the surrounding rooms: a yell here, a thud there; a projected monologue creeps into our chat, and a scream grates through my recording.

“The independent scene is full of people,” Metwally tells me. “Walk into any rehearsal room, and there’s a troupe; I can barely book a slot. Personally, I know at least 50 directors, with a troupe each. It’s both a weakness and a strength – how anyone can do it, and everyone is doing it.”

Most of these troupes operate in a parallel system to the “official” scene that functions under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture, which owns all the major theatres in Egypt. The 22 publicly-owned stages, 17 of which are in Cairo, aren’t open to all: directors need to be members of the Actors’ Syndicate to have their plays performed there, and only a fraction of their cast is allowed to be non-syndicated.

The process to enter the syndicate itself is often long and arduous for independent artists, which has created what some industry veterans call a closed clique of theatre creators.

As a result, many independent directors flock instead to private theatres, which offer avenues for experimentation away from the bureaucracy of the public stages. The issue, however, is that only a handful of private theatres remain.

“It all comes down to money,” says Dr. Dina Amin, associate professor of theatre at The American University of Cairo (AUC) and director of the university’s theatre programme. “To buy a venue, and then rent it out to individual artists, you need enormous capital. It’s great that a few of these centres exist because they’re absorbing a lot of young artists.”

Alhosabir Theatre in Ezbekiyya, which used to host Samir Ghanem’s own comedy troupe, The Limelight Trio (Tholathy Adwa’ El Masrah), in the 1960s, is the oldest private theatre still catering to the independent scene.

The AUC’s Falaki Theatre, the Jesuit Cultural Centre’s El Nahda, and El Sawy Culture Wheel are all available for rent, at varying price points. The Rawabet Theatre, which many young creatives treasured after the 2011 revolution for offering a powerful space for collective reflection, has recently reopened as the Rawabet Arts Space. (It had closed in 2019 when the team was unable to renew its lease, after an uphill battle so save the gallery which had owned it.)

The relative accessibility of these stages means troupes can come in and experiment. But with directors often financing productions from their own pockets, most runs last less than a week.

“The biggest issue in the theatre scene is funding because we don’t have producers of theatre,” explains Amin. “If you look at cinema, there are known producers, some of whom will take risks on young artists. But theatre doesn’t have that. The only major producer of theatre is the state, and artists who don’t have access need to raise the money from other sources. Many of them will work other jobs to fund their interests, they’ll get creative, they’ll carve their way up.”

No underdog

Director Hassan El-Geretly, now in his 70s, is a prime example of the resilience of theatre artists. In 1987, he established El Warsha, Egypt’s oldest independent theatre troupe. Its actors have included Egyptian household names Abla Kamel and Sayed Ragab. This year, as El Warsha turned 34, it nearly had to shut down due to financial difficulties.

With the odds seemingly stacked against them at every turn, young theatre-makers were quick to challenge any assumption of the genre as a kind of underdog

In its early years, it performed the work of world playwrights like Peter Handke and Franca Rame, even adapting Franz Kafka’s In the Penal Colony for the 1989 Cairo International Festival for Contemporary and Experimental Theatre, while also staging classics of Egyptian folk heritage. It now survives because of its partnership with civil society groups, offering services to organisations and workshops in different art genres and facilitation training.

“We have a chronic problem in Egypt, how formal cultural institutions completely ignore the independent scene, even though we’ve proven our worth time and again,” El-Geretly told Bab Masr in a video interview earlier this year, emphasising the many occasions when El Warsha was invited to represent Egypt in international performances. “But here, you can’t be on your own. You need to be connected to the commercial scene, or the government; independence is still a difficult concept for us to accept.”

Even so, with the odds seemingly stacked against them at every turn, young theatre-makers were quick to challenge any assumption of the genre as a kind of underdog. Stage director Mohamed Gabr, who has been putting on shows for two decades at universities, youth centres, and private theatres, thinks the theatre scene is currently at the most vibrant point since he started.

“When I started in the early 2000s, private sector theatre was at the end of its prime,” Gabr says. “It had peaked in the 1990s when downtown Cairo and Emad El-Din Street were full of theatres. And then independent theatre shrank, bit by bit until it came to a halt around 2010. The only people showing up to plays were those already in the field.”

According to Amin, what happened in the 2000s was the aftermath of a free theatre movement that began in the 1990s, led by the late writer and “theatre activist” Nehad Selaiha, the so-called godmother of independent theatre. By the mid-2000s, institutional support for the independent scene had dwindled, shrinking the field significantly, until the revolution in 2011.

“With the stage in the square, there was a moment of appropriating public space, having the freedom to perform anything, in any genre you wanted,” Amin recalls. “There was this hopeful moment that followed, that Egyptian theatre was coming back to the hands of young theatre-makers. And then it fizzled away, and things went back to the way they were.”

Resurrection after the revolution

Laila Hosny, who stars in Metwally’s current one-woman show, says that popular interest in theatre has been growing immensely over the past few years. She credits this renaissance to one play, directed by Gabr, part of the hopeful moment Amin remembers.

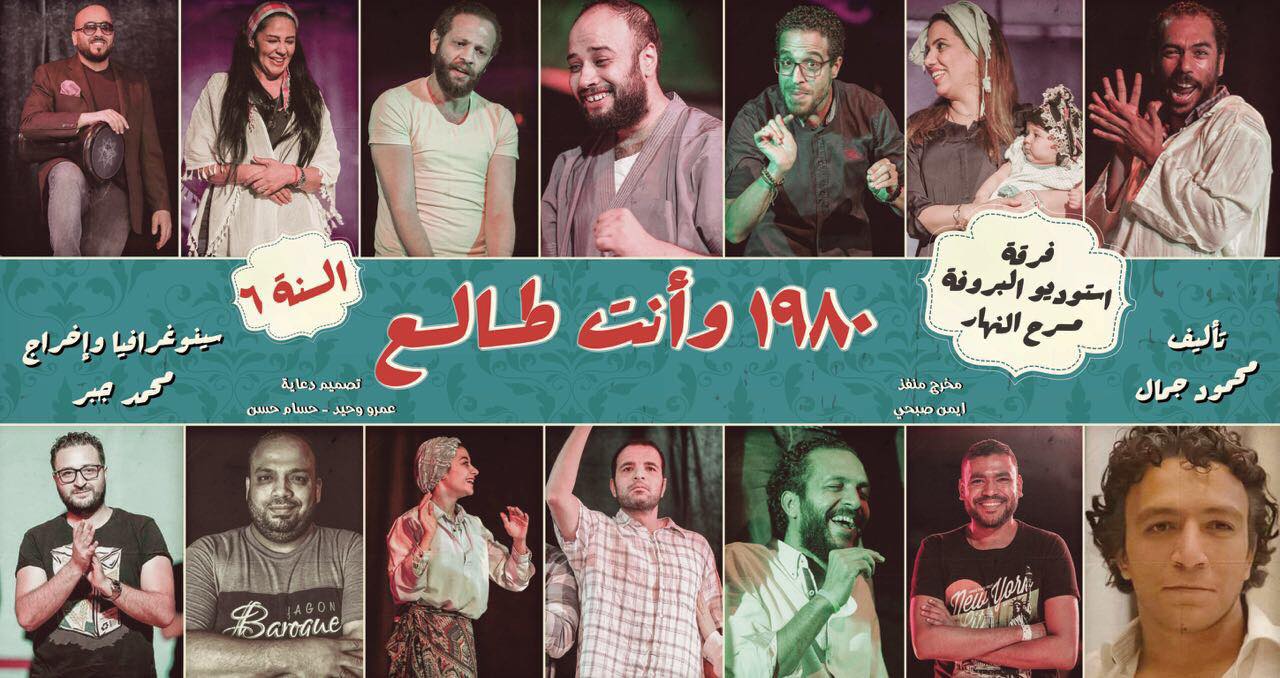

1980 and Above (1980 Wenta Tale'), directed by Gabr and staged at the Alhosabir Theatre, ran seasonally from 2012 to 2019. A large part of those involved in the independent scene today, Hosny explains, say they only got into theatre after watching 1980, a television performance of which is available to watch in full on YouTube.

First shown in January 2012, the play’s focus was simple and perfectly timed for post-revolutionary fervour: the lives and plights of the youth. In a sequence of dramedy sketches, the play tackled the lives of Egyptian millennials, through ambition, to despair, parental expectations, a stillborn revolution, young couples rustling up money to get married, and hashish-addled bro hangs.

Even with a liberal dose of piano melodrama and preachy monologues, 1980 is a strong product of its time, with a surprising amount of pointed political satire, considering the censored environment at the time.

Once word of the show spread, crowds began pouring in. It became a cultural phenomenon, with five to eight shows a week between Cairo, Alexandria, and Port Said. Each show sold out to 650-700 attendees, with regular standing-room only showings. By the time they wrapped for good in 2019, Gabr estimates total viewership at around 1 million.

Over its seven-year run, the play was constantly updated. Sequences were edited and political jokes switched out as the regime changed in 2013. According to Gabr, it was that mixture of youth, comedy, drama, and novelty that drew audiences in. “It was real, it was young, it was funny but human, and it was about our generation,” he says.

“This is part of why audiences abandoned theatre for so long,” he says of the in-between he tries to strike with every production. “Most plays either go right over mainstream audiences’ heads, or are just comedy for comedy’s sake. Both kinds target small, opposite sections of the population. But there’s a huge audience in the middle that’s both cultured, and wants to be entertained on a night out.”

Breaking even in a broken market

According to Gabr and Hosny, the success of 1980 and Above showed young performers that independent theatre is a viable outlet, encouraging them to put together troupes, rent out small theatres, and stage spirited but minimalist productions.

Over the past decade, two more players have also joined the realm of private theatre, at much larger levels of budget and celebrity. Productions by private company Cairo Show, whose star-studded casts have included Yehia El-Fakharany, Mohamed Henedi, and Ahmed Ezz, often debut or stage short showings in Saudi Arabia, in addition to their runs at the Marquee Theatre in New Cairo.

More polarising is actor Ashraf Abdel-Baky’s comedic theatre anthology series Teatro Masr, five seasons of which have aired on the Saudi-owned MBC channels and are now available on Shahid.

Despite the former being prohibitively expensive for most audiences, and the latter being deeply unfunny, both are arguably playing an important role, fostering theatre skills in young actors, as well as contributing to a theatre viewing culture.

'Egyptian theatre seems to be constantly trying to replicate what we had in the 60s and 70s and 80s, when we had these amazing well-written comedies, with really good actors'

- Moustafa Khalil, Egyptian director and playwright

“We need all of them,” says Amin. “You can say whatever you want about how something might not cater to the well-versed, but at the end of the day, everything is contributing to the resurrection of theatre.

"We need the Broadway for those who can pay for it, we need the off-off Broadway for the independent and experimental, we need all of it because the market is empty.”

But director and playwright Moustafa Khalil, who leads the Kenoma Theatre Company in Cairo, laments the current situation. “I think the theatre market is broken,” he says.

“Egyptian theatre seems to be constantly trying to replicate what we had in the 1960s and 1970s and 1980s, when we had these amazing well-written comedies, with really good actors. We had this expression of comedy that we’re trying to recreate now, but it’s outdated.”

Kenoma is best known for producing small English and Arabic adaptations of plays from the world theatre canon, most notably Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter. With casts mainly composed of graduates from AUC’s theatre program, Khalil prides himself on putting together shows that are theoretically sound. But he is well aware of the material issues that arise with independence.

Over the eight plays that he has staged, both before and after founding Kenoma, the only time ticket sales have turned enough revenue to pay actors or himself was his 2016 production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot at the Falaki Theatre, which featured professional actors.

For every other play, Khalil and Kenoma co-founder Abdelrahman Safwat – like nearly everyone in the scene – fund productions from their full-time jobs. The best-case scenario, after accounting for rent, taxes, censors’ fees, and set construction, is to break even.

Their latest production, Al Makhzan (The Warehouse) was an Arabic adaptation of Quentin Tarantino’s 1992 film Reservoir Dogs, at the recently reopened Rawabet Art Space downtown. Even with a grant that covered half their production budget, Khalil considers it a success that they only incurred a loss of a few thousand Egyptian pounds.

“How much money you can make all depends on the marketing you can pull off,” Metwally explains. “As a director, as a cast, if you have an audience that will come see you every time, that makes selling tickets easier. But that’s why I personally prefer festivals, so I can avoid becoming more of a salesman than a director.”

On the precipice of a renaissance

According to Amin, her generation greatly benefited from the government’s support of experimental theatre in the 1990s. When she was appointed director general of the Cairo International Festival for Contemporary and Experimental Theatre when it was revived in 2016, she meant to pay it forward. Without a budget for workshops, Amin invited friends from around the world to give small workshops for free.

'We were met with these thousands of young people who were dying, not just to get on stage, but to learn new approaches, if we would only open the doors for them'

- Dr Dina Amin, Associate Professor of Theatre at The American University of Cairo

“The day I opened registration for the very first round, I got 1,500 applications for every single workshop,” she recalls.

“Suddenly, we were met with these thousands of young people who were dying, not just to get on stage, but to learn new approaches, if we would only open the doors for them.”

“There’s not that many places to practice your craft as a theatre actor,” says 24-year-old stage and screen actor Ali El-Shourbagy.

“You’re always either not making money, or spending your own to be in a workshop and stay fresh. There’s the drive, and there are the people who want to do it, but it’s always going to be an issue of money.”

It’s not that there are no opportunities, or that there are no doors that open to success. Supported by the Ministry of Culture, for instance, the Artistic Creativity Centre runs the Actor’s Studio, an annual acting workshop led by celebrated Egyptian director Khaled Galal.

Over a six-month audition period, Galal chooses 100 participants from the thousands that apply, who are then usually filtered down throughout the program to the 50-70 who make it to the final production. Many of the best-loved actors that have emerged in the entertainment scene over the past decade, including Mohamed Farrag, Mohamed Mamdouh, and Bayoumi Fouad, are graduates of the studio.

“There needs to be a Creativity Centre like Khaled Galal’s in every governorate in Egypt,” says Amin. “A state-sponsored program that graduates artists after rigorous training: can you imagine the quality of artists we would have if we had more of these centres? There’s no one incubating these young artists, that’s why there’s this void.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.