Lehnert & Landrock: The lost world of Egypt captured by famed Cairo studio

It was on an ordinary day in 1982, while wandering around the bookshop he ran with his father in downtown Cairo looking for space to store new volumes, that geologist-turned-librarian Edouard Lambelet spotted a big box hidden under a layer of dust.

Lambelet had only recently left his job at the oil giant Shell to go to work there, so he was still trying to adjust to a place that his dad knew like the back of his hand. Inside the abandoned box, Lambelet found a vast collection of glass photographic plates.

“I asked my father [what it was], and he told me it was old stuff, old photos,” he recounts to Middle East Eye. “You can throw them away if you want, I never had the heart to do it,” he remembers his father saying. “And thank God he didn’t,” Lambelet, now 85, added.

Inside that box, as Lambelet was then about to discover, lay the decades-long work of a popular photo studio founded by Rudolf Lehnert and Ernst Landrock in Cairo in 1924.

The studio had built up a remarkable name, and a collection of some 6,500 photos offering an extraordinary insight into Egypt and North Africa at the turn of the last century.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

An accidental partnership

Lehnert was born in what is today the Czech Republic in 1878. After completing his studies in graphic arts in Vienna, he set out on a long journey on foot, camera in hand, that took him first to Palermo and then to Tunis following a boat trip of almost 20 hours.

At the time, taking a photograph was a long and sophisticated process. But Lehnert soon discovered that in Tunisia it was much easier because of its light, and he began to fall in love with the charm of the place.

After living in Tunisia for a year, Lehnert walked back to Switzerland, and it was there that he met Landrock, born in German Saxony also in 1878, by chance.

The two decided to start a business together, and headed back to Tunis in 1904. Lehnert’s photos were successful for his use of light and shadow, as well as his depictions of fertile oases, pristine deserts and Tunisian women.

However, their adventures in Tunisia came to an abrupt end with the outbreak of World War One. Being two German speakers and owners of a camera made them at that time almost automatically potential spies, so they were arrested by the French and sent to Switzerland.

When they decided to pack their bags and go on the move again, they headed to a new destination: Egypt.

Capturing life in Egypt

According to Lambelet, the two were eager to head to Egypt and capture life there, intrigued by what they would find.

“Within our family there is a story saying that the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun [in 1922] was what pushed them to come to Egypt,” Lambelet said.

After arriving in Egypt, the two divided their work. Lehnert was responsible for travelling all over Egypt and taking photos, while Landrock would run a photo studio in the heart of Cairo.

After six years of intense work, Lehnert decided to return to Tunisia and handed over the copyright of his photos to Landrock, who remained in Cairo and continued his business on the bustling Sherif Street, until he later passed the legacy to his stepson, Kurt Lambelet.

Lehnert eventually made a name for himself as a renowned portrait photographer in Tunisia before moving to the southern oasis of Gafsa, where he died in 1948.

Landrock, meanwhile, went on holiday to Germany in 1939 and was caught up in World War II. By the time the conflict was over, he felt too weak to return to Egypt.

From then on it was Kurt, the father of Edouard and the only one who had never left Cairo, who took on the responsibility of continuing the business – and saving its legacy.

Rediscovering and restoring the photos

When Edouard Lambelet found the glass plates, he had no idea what to do with them, so he asked an employee who had some knowledge of photography to try to develop them in a small laboratory with old-fashioned machines that they kept in the shop.

“I gave him ten glass plates at a time, which were quite heavy, and told him to make two copies of each,” Lambelet said. “With that old equipment and awful paper, he managed to do a decent job. I was very surprised,” he added.

When they had developed a decent number of photographs, the story of the treasure trove appeared in the French newspaper Liberation. And demand skyrocketed.

Soon after, Lambelet contacted a museum of black and white photos in the Swiss city of Lausanne, the Musée de l’Elysée, and they agreed to send and deposit there more than 300 kilos of photographic plates, films and other original documents of the collection.

The task of restoring the pictures to their original high-quality state was undertaken by a young Canadian photographer, Chris Langtvet, who was interested in old development techniques. He offered to produce negatives and internegatives of all the glass plates, including those already in Lausanne.

“He designed a system that turned out to be extremely successful,” Lambelet noted.

Revealing stories from Egypt

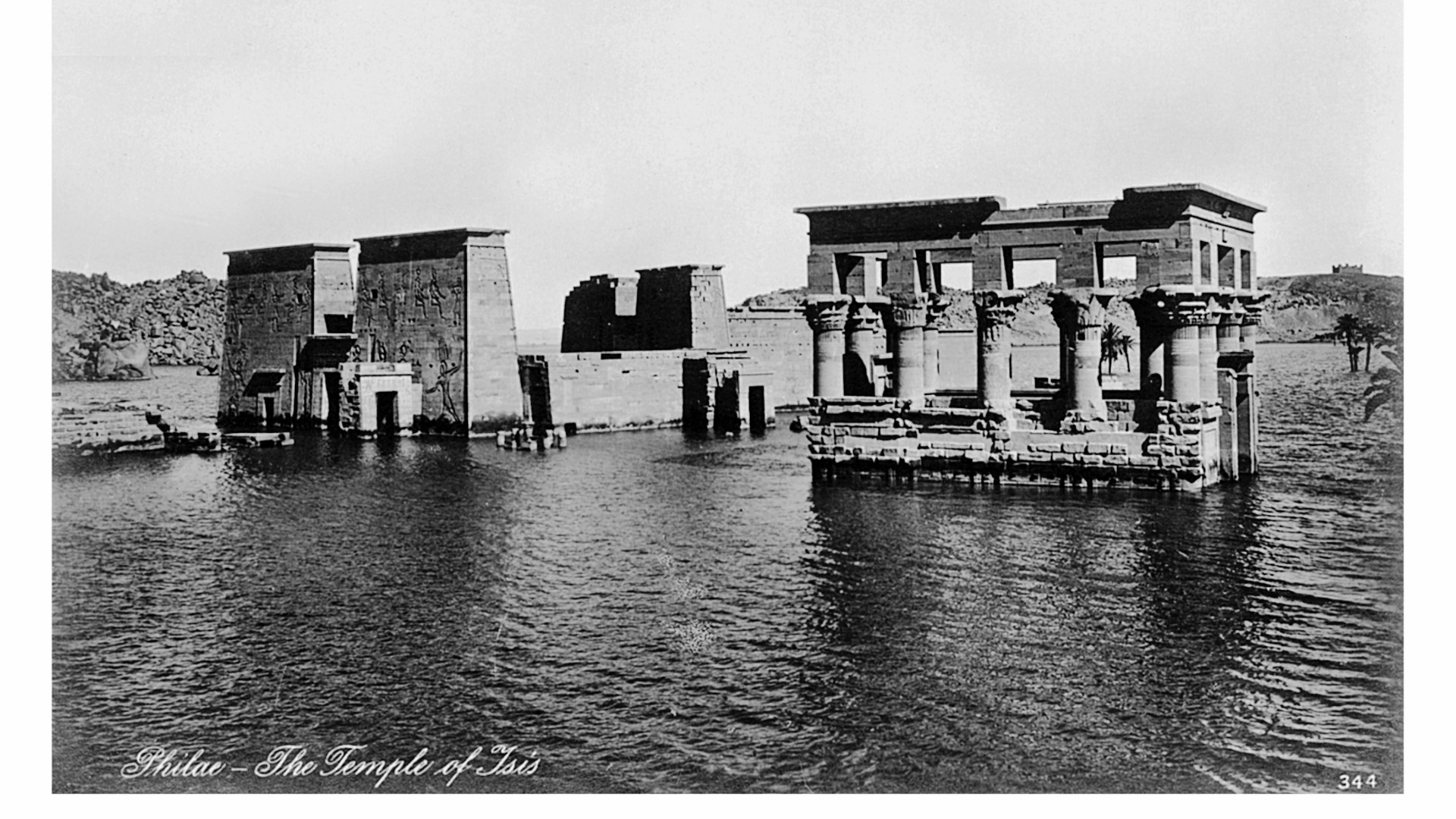

The collection of photos, which was comprised of 6,500 images, revealed various stories from around Egypt and spanned cities from around the country, including Luxor, Kom Ombo, Edfu and Aswan in the south; Alexandria, Cairo, and the Suez Canal in the north.

The legacy left by the collection is largely that of an Egypt that no longer exists.

Of Cairo, for example, Lambelet says that they have beautiful photographs of the iconic Shepherds Hotel, which he believes was “the best hotel in the Middle East at the time”.

Another testament to that bygone era are the images of the zeppelin that Lambelet says arrived in Egypt in 1931 and offered expensive day trips from Al Maza airfield, then near Cairo, to Jerusalem across the skies of Sinai and then back.

In Alexandria, some of the most precious photographs are those of the city’s old Cotton and Stock Exchange, once one of the leading bourses in the world, but which was burned down during riots in 1977 and demolished in 1982.

“Today, these are all historical documents,” Lambelet said.

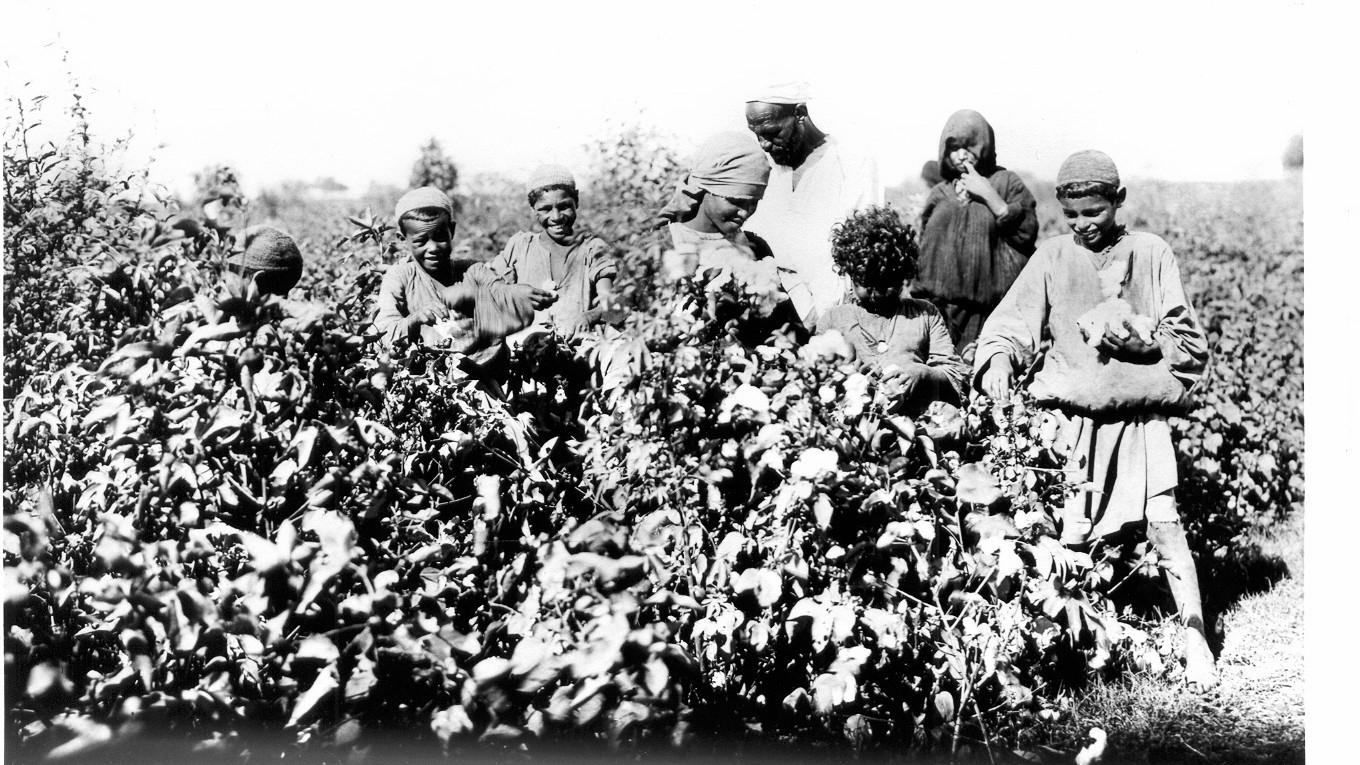

Lehnert’s photographs also portray what Egypt’s countryside looked like a century ago, including old irrigation techniques such as the shadoof, a counterweight system made of a long wooden pole with a container on one end and a weight on the other.

Lehnert and Landrock’s images became so popular that they even appeared on several Egyptian banknotes in the early 20th century.

However, it has not been easy to determine all of the stories behind the photos. For some, it has proved to be more of a puzzle due to the absence of written documents.

After assessing the photos, Lambelet believes that around 200 of the photos could not have been taken by Lehnert, and must have been purchased or arranged by a photographer from the Egyptian Museum of Antiquities.

A living legacy

Today, the legacy of Lehnert and Landrock continues to live on, attracting curious visitors and admirers alike to a shop tucked away on a busy street in the heart of Cairo.

There, in a modest lab, they carry on making manual prints of Lehnert’s photographs, following his same technique and using internegatives from the original glass plates.

“Few clients come, but people who are really interested in these photos buy a large number,” Lambelet said.

As the collection is about to mark 100 years in Egypt, Lambelet is also finalising a book on its story with the aim of having it ready for publication around December next year.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.