Five of the best Arab comic and graphic novel releases of 2021

Over the past decade, an increasing number of young Arab writers have adopted graphic novels and comics as their main means of artistic expression.

For them, the format lends itself better to capturing the absurdities of the young Arab experience than either prose or film.

Inherently otherworldly, comics have the flexibility to blend the fantastical and the mundane, encapsulated, for example, in the image of a donkey bumming a cigarette on a Cairo street corner in Egyptian artist Deena Mohamed’s Shubeik Lubeik (Your Wish is My Command) trilogy.

For Lebanese comic artist Rawand Issa, who has recently released her debut graphic novel Fy Batn El Hoot (Inside the Giant Fish), the ability to show a single frame at a time holds enormous potential.

“You have an entire scene in a single frame, which means the reader’s imagination is free,” she tells Middle East Eye. “It’s up to you to fill in what the movement could be, bring your own insight into the story. That’s what I love about comics.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The format's versatility can also give readers access to issues they might otherwise not have been able to.

Heba Abd El Gawad, an Egyptologist and UCL researcher, collaborated with three comic artists/initiatives for her project, Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage, which aims to educate the public on the colonial legacies of Egyptology

"We turned all this academic research and technical jargon into simple comics that anyone can understand and form an opinion about,” Abd El Gawad said in a panel at Cairo Comix, which was held at the Mahmoud Mukhtar Museum in Cairo in November.

Graphic novels, she explained, create a distance that makes even the most difficult and harrowing subjects more digestible.

It’s this aspect of the format that makes works like Waat El Shedda (Time of Need), which tackles a tragic famine in Fatimid Cairo, a much easier, if still chilling, read.

Here Middle East Eye looks at five notable graphic novels and comics published in 2021, which deal with issues as diverse as beach gentrification in Lebanon and the ghouls of Tunisia.

1. Time of Need (Waat El Shedda)

In 1071, Fatimid Egypt suffered through seven years of misery when the Nile’s waters declined and caused a widespread famine, depleting food supplies and spreading disease among Cairo’s residents.

By the end of the famine, a third of Egypt’s population was dead.

Time of Need chronicles the famine through the eyes of ‘Am Yehia, an undertaker who goes door to door collecting the bodies of the dead by the thousands each day, and Maymoun, a mischievous boy he befriends.

The sweeping story is rigorously researched and populated with compelling characters, and - though less than 100 pages long - develops the key relationships remarkably well.

As a result, it is a work that charms with its attention to detail, and succeeds in carrying the right emotional weight.

“When I first learned about this time period, I was taken aback by how little has been written about it, especially when you get to know how awful it really was,” author Mahmoud Refaat told Middle East Eye.

“It was really important to us that it didn’t read like a textbook. The characters are fictional, but all of the events in the story are real, and we tried to turn them into a whole world.”

2. Inside the Giant Fish (Fy Batn El Hoot)

With her debut graphic novel, Lebanese writer and illustrator Rawand Issa crafts a delicate narrative based on her experiences growing up in and then losing her hometown of Jieh, 23 kilometres south of Beirut.

Against the backdrop of privatisation, dispossession, and economic violence, we experience a 1980s childhood spent on the beach, full of French fry sandwiches, children’s seafaring adventures, and teenagers smoking argileh under sugarcane canopies.

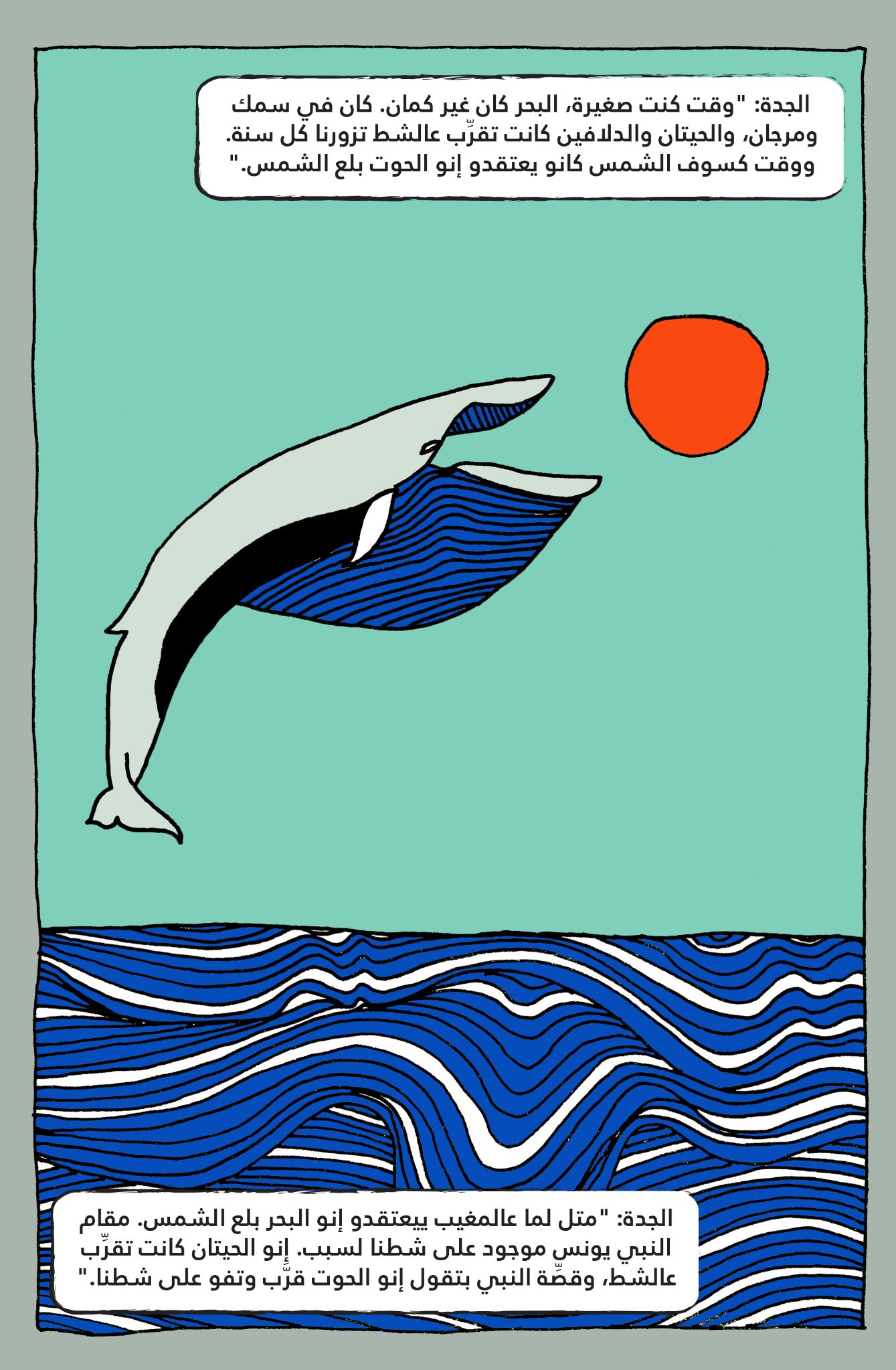

In Issa’s signature style - all sharp facial features and bright palettes - the story blends coming of age with sectarian violence, immigration and exile with the spiritual significance of the titular whale.

Jieh, Issa explains, is the site of a shrine to the Prophet Jonah or Younes, who was swallowed by a whale.

“The Maqam of Nabi Yunus is on our shore for a reason,” the protagonist’s grandmother says, reminiscing about a time when whales and dolphins were so plentiful off the coast that you could swear a whale swallowed the sun every day at dusk. “The whales would come so close, that the story goes that one breached and spat the prophet out onto our shore.”

With the entire coastline privatised for use as beach resorts and much of Jieh’s youth emigrating from the country, Issa felt compelled to produce a picture of her hometown that her young nieces and nephew - to whom the graphic novel is dedicated - will never know.

“It was really heartbreaking to see how the new generation would know nothing of these memories we have of Jieh and the sea and the village,” Issa told Middle East Eye.

“They would never know how we grew up, what the sea meant to us. The geography of the space colours your identity, and they won’t have the same identity we once did.”

Issa is currently in the process of translating Inside the Giant Fish into English and it will be available in the US soon.

3. Legends of Fear (Asateer El-Khouf)

“History turns into legend, and legends turn into myth.”

So begins Legends of Fear’s third story, which takes place in the year 1014 inside the home of Ibn Sina; the great physician, astronomer, and thinker of the Islamic Golden Age.

The great scholar struggles to treat a man with an unfamiliar and bone-chilling illness, and is forced to face the limits of his genius.

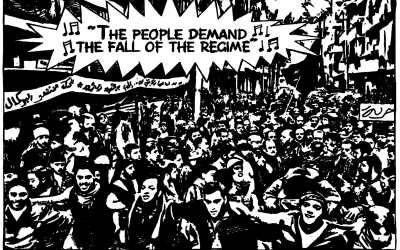

The 10 comic shorts by different artists deconstruct and repurpose stories from Tunisian and Egyptian history, culture, and folklore, and are bound together under the theme of "fear".

Some of the stories feature historical characters like Ibn Sina, while others remain in the realm of primordial myth. Some are black and white, deploying sketch-like illustrations for a haunting effect, while others are in full colour.

On the whole, the anthology is more than an inert meditation on fear as a theme in Egyptian and Tunisian culture.

It also explores the role scary stories play in enforcing social control, both in getting children to obey the "soft voices of authority" emanating from mothers and grandmothers, as the book’s preface reads, and the cautionary tales for adults that guarantee obedience to autocrats.

The final two stories do this especially well, exploring the domestic terror of patriarchy and a courtyard-bully-turned-tyrant, respectively.

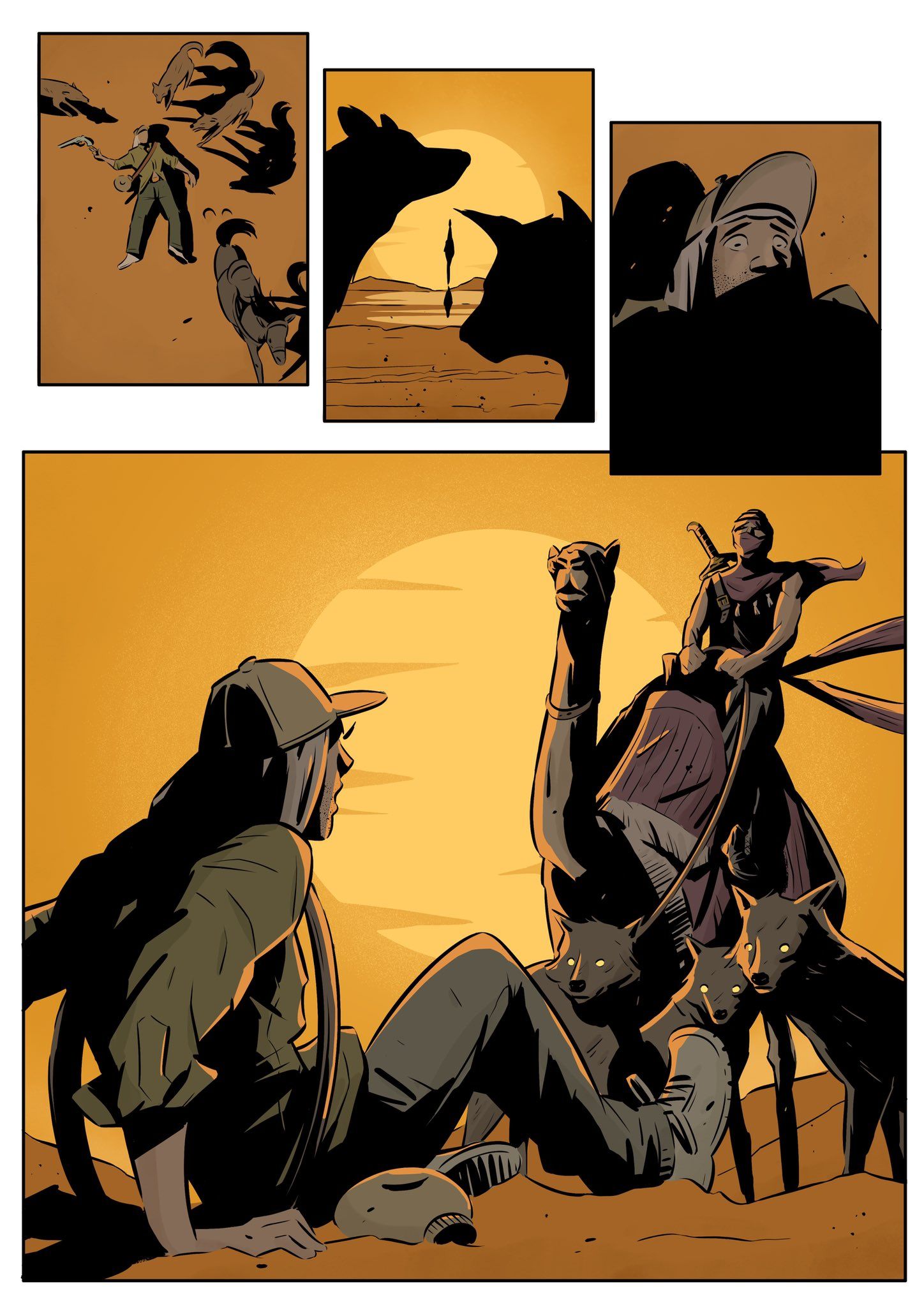

4. El 3osba (The League)

Available to read for free online in both English and Arabic, this collection of five short stories follows an ensemble of superheroes as they confront colonialism and heritage theft.

El 3osba, a band of Egyptian superheroes created in 2015 by John Maher, Ahmed Raafat, and Maged Raafat, include the present-day reincarnation of the Ancient Egyptian god Horus, a shape-shifting microbus driver who can control fire and dust, a rogue Bedouin mercenary in love, a young doctor who can use her healing powers to control people, and an Egyptian intelligence officer who casts spells.

The issue is released in collaboration with Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage, a dialogue initiative by University College London researchers Heba Abd El Gawad and Alice Stevenson to create a conversation around the politics and colonial legacies of Ancient Egyptian heritage.

Each of the five stories tackle the issue from a different angle. The first, Home, is based on the real story of an ancient Egyptian artefact found in the Matareya district of Cairo, and its impact on the local community.

Another is a villainous portrayal of Flinders Petrie, an English Egyptologist who is hailed as the father of archaeology, but was also a known eugenicist who was complicit in large-scale artefact smuggling.

The collection of shorts is not perfect; the third story, for example, is supposed to be a feminist reimagining of history, but is told from a male saviour perspective that over-sexualises the ensemble’s one female superhero.

Such criticism notwithstanding, the collection is an intriguing blend of Marvel and National Geographic, spotlighting elements of history usually hidden from view.

The last story, Honour the Dead, is a stand-out and tackles the grotesque nature of Egyptomania. It frames a single disturbing truth in a new light: the mummies Europeans would host soirees around, unwrap, and grind into powder for their snuff boxes and paint palettes, were real people ripped from their graves, who deserve to be returned to their resting places.

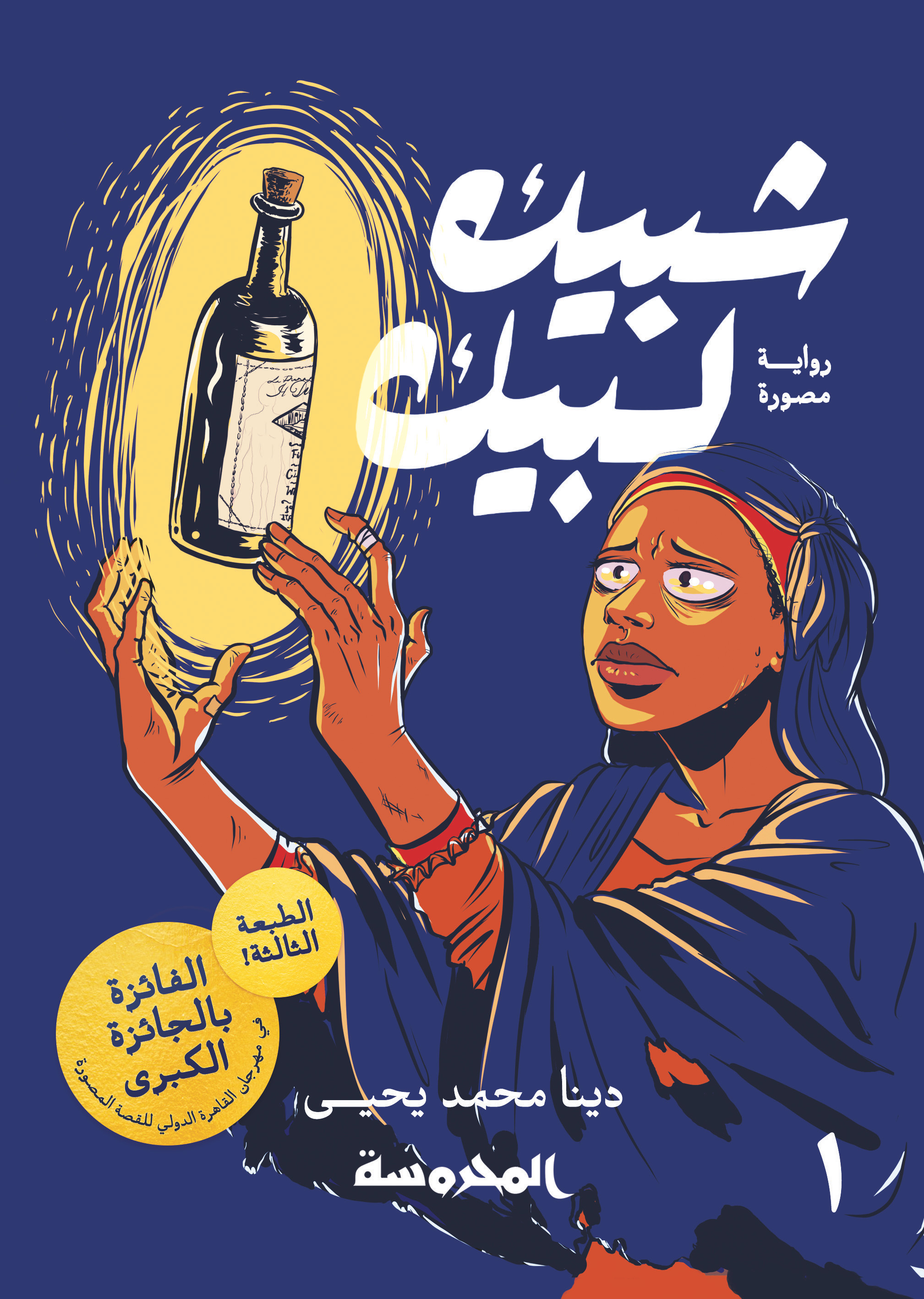

5. Your Wish is My Command, Issue 3 (Shubeik Lubeik)

Egyptian illustrator Deena Mohamed has been a force in the regional comic scene since her 2013 debut web-comic Qahera, about a visibly Muslim Egyptian superwoman who fights misogyny and Islamophobia.

Her award-winning graphic novel trilogy Shubeik Lubeik, an urban fantasy about wishes, combines magical realism, class analysis, mental health, and colonial legacies, to astounding effect.

The premise of the story is that wishes are for sale, commodified into classes where the more expensive a wish is, the better it works. Each story focuses on a first-class wish and a character who needs it.

The world-building is thoughtful and the plots are skilfully planned, but the trilogy’s greatest attributes are the empathy and insight with which Mohamed crafts her stories.

As a result, the trilogy has been far more popular than Mohamed or her publisher, Dar El Mahrousa, imagined.

“I only find out about [people’s reactions] through events like CairoComix,” Mohamed says.

"There were people coming to me with their copies from Alexandria...someone from Assiut sent a friend so they could talk to me over the phone and explain which posters they wanted.

"After two years of working alone, it was definitely a little overwhelming to realise more people really enjoyed these books than I previously realised.”

The English translations for all three parts of Shubeik Lubeik are slated for publication in Spring 2022 from Pantheon Books for North America and Granta for the UK.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.