Five video games set in the Middle East you need to know about

The Middle East has been a growing market for video games for years now, with franchises like FIFA, Minecraft and Fortnite counting young people from the region among their most ardent fans.

Urban centres from Istanbul to Casablanca are dotted with video game cafes, often emblazoned with the Playstation logo or lifesize vinyl posters of heavily armed characters advertising the Call of Duty series.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In gaming tournaments too, competitors from the region are well represented, with one Saudi gamer, Mosaad al-Dossary, picking up more than $560,000 in prize money playing in FIFA tournaments.

While gaming as a hobby has a wide reach in the region, when it comes to representation within video games, it’s a different story.

Generally speaking, there are few non-white protagonists taking the leading roles in stories within games, although that’s slowly changing, with the likes of the Yakuza and the Life is Strange series.

Middle Eastern characters and settings are fewer still, with many of the characters that are present taking the form of two-dimensional stock villains or anonymised targets to shoot at.

That said, the trend is not universal, with the examples below proving the region can offer inspiration for storytellers in the industry.

Prince of Persia

Although the original game made its debut way back in 1989, Prince of Persia (PoP for short) was cemented into the gaming mainstream after its 2003 Sands of Time reboot. The story follows an unnamed prince travelling through India with his father to visit a sultan. There, he stumbles across the so-called dagger of time, which gives the user the power to reverse and stop time. You’re tasked with defeating enemies using these mystical powers, but also the power of acrobatics as you move across different platforms to reach safety.

PoP was highly notable at the time (and unfortunately, remains so) for being one of the few games led by a big-name publisher (Ubisoft) to have featured a Middle Eastern protagonist, and to have its story take place in the region. Aside from an upcoming remake of this particular entry, what’s unusual is how the series has remained largely dormant for years. Sands of Time led to three separate sequels, with all titles receiving positive reviews and commercial success. It also led to a Hollywood film in 2010, but its cast headed by Jake Gyllenhaal was widely seen as a whitewashing exercise, with even the actor himself admitting he regretted taking the role.

There was also a standalone PoP game released in 2008, distinct from the rest of the series in its story, style and tone. It follows a bandit-like prince helping to restore order in a mystical and imagined Persia. The most interesting element in the game was its use of Zoroastrian motifs and symbols. The religion, once widespread in Iran, has a small following today.

Journey

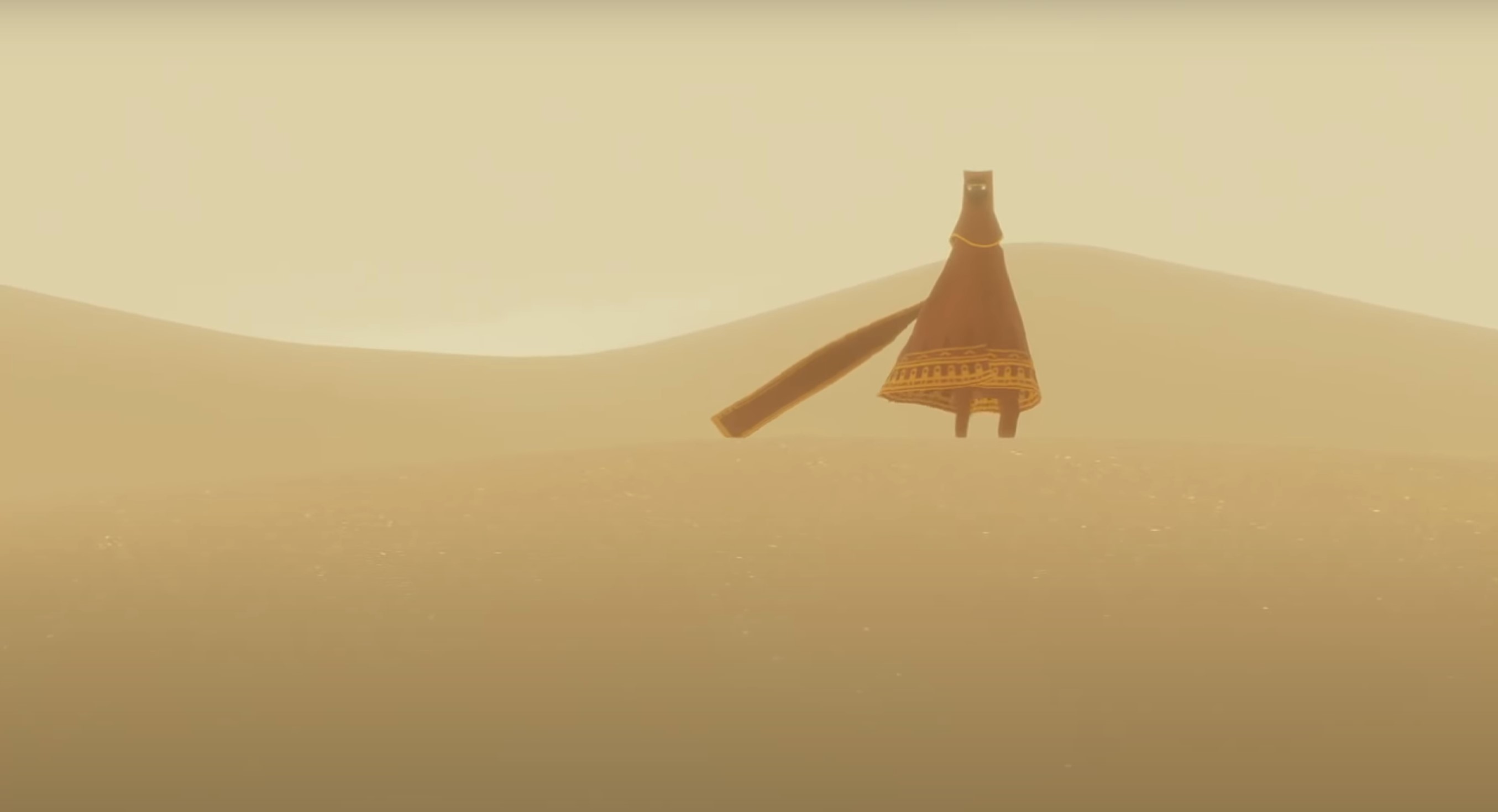

Journey follows an unnamed robed character travelling across changing and tumultuous desert environments as they attempt to make their way towards a distant mountain with a split peak.

The traveller the player controls doesn’t have any facial features, with glowing eyes being the only human element visible across the shadowy face.

Besides gracefully floating and skidding across desert landscapes, the character also emits a chime, which can be used to communicate with other players, as well as increasing the length of their flowing scarf, allowing them to jump and fly over short distances. The sound also focuses the character’s attention on abandoned sites, which then reveal images illustrating the rise and fall of a now sand-covered lost civilisation.

For a game without dialogue and little explicit exposition, Journey is packed full of symbolism that borders on the religious. Indeed, creator Jenova Chen has admitted he intended to create a “church experience”, which would leave gamers in “awe”. But pinning down the exact meaning is left to the player.

For this author, the game’s Middle Eastern desert setting suggested something rooted in the teachings of Abrahamic faiths, but the idea of rebirth after struggle also hinted at Buddhist themes.

Assassin’s Creed Origins

When the series first launched, the Assassin's Creed franchise allowed players to take control of Altair, a member of the Assassins, the infamous Ismaili military order, which elaborately dispatched its enemies, both Muslims and Christian, in sensational murders, sometimes intricately planned over years.

The developers then decided to make the series global, setting stories in the Revolutionary War-era United States, Italy during the Renaissance and Victorian England.

In 2017, the series returned to the Middle East with Origins, which takes place in ancient Egypt at the end of the Ptolemaic period, around 50BCE. The basic formula of the free-running, wall-jumping, near-invincible killer remains and the story revolves around a desert patrolman, or Medjay, named Bayek of Siwa.

Ostensibly a tale about Bayek’s quest for vengeance after he inadvertently kills his son in a melee with a group of masked men, the protagonist finds himself caught in a struggle between the Hidden Ones, a precursor to the Assassins of the original game, and the Order of the Ancients, from whom the antagonists of the series, the Knights Templar, descend.

A game imbued with high political intrigue, the developers also took the decision to turn its vast open-world setting into an educational tool.

The game was updated a few months after release with a “discovery tour” mode, which removes all combat and turns the game into a living museum. There are over 70 tours, each focusing on a particular aspect of ancient Egyptian life, all created with the help of universities and historians. The tool proved so popular that it’s available separately for those not interested in the game itself. It’s a shame this gold standard of interactivity hasn’t since become a common feature throughout the industry.

Heaven’s Vault

Heaven’s Vault is a game also set in an indeterminate North African/Middle Eastern setting vaguely resembling Journey. You play as an archaeologist named Aliya Elasra, who is asked by a superior to find a fellow researcher who’s gone missing, and is forced to take a robotic companion named Six with her.

The headscarf-wearing protagonist with an Arabic-sounding name takes on the challenge reluctantly, albeit with her curiosity piqued by the circumstances of the researcher’s disappearance. Like any archaeologist, Elasra collects samples from different ruins and artefacts as she seeks to solve the mystery.

Steeped with ancient Egyptian themes, the player has to decipher a hieroglyphic script belonging to a lost civilisation, known only as the Ancients. The developers at Inkle studio say they created over a thousand words in this fictional language.

Heaven’s Vault differs not just from other narrative games, but also those with multiple outcomes and dialogue options. That’s because the choices you make via Elasra can mould her personality and how she’s perceived. The choices a player makes reveal themselves as variations in the character’s tone and personality. She can make herself cooperative and pragmatic, or assertive and even disdainful, depending on the situations she finds herself in. The creators should be commended for creating such a unique and memorable character.

Civilisation VI

The Civilisation series has kept gamers in trance-like states in front of their screens since the days of monitors lit by cathode ray tubes.

Starting with a small square plot of land, players control a group of humans, initially just one or two, as they go about creating settlements using the resources and geography they encounter. Over time, rival settlements appear and the player must decide on the best course of action: cooperation or warfare.

Fast forward three whole days of gameplay and a player will have established world domination and will be making their way to the Sun’s closest neighbour, Alpha Centauri, to establish a new civilisation.

A game so rooted in history cannot avoid mention of the Middle East, especially considering the area’s role in birthing civilisation and providing the backdrop for the world’s most powerful empires.

In this sense, the developers do not relegate the region and its personalities to the role of side characters but ensure they are well-rounded characters and pivotal players in the action.

One notable example in this respect is the character of Cyrus the Great, the legendary founder of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, whose realm stretched from the shores of the Bosphorus to the banks of the Indus and existed in some form between 550BCE and 330BCE.

Some effort has gone into making sure the in-game Cyrus and the historic monarch share common traits. Cyrus’s real-life historical expansionism is reflected in the in-game version's eagerness to launch surprise invasions of a player’s territory. A player controlling Persia is also rewarded in the game when they imitate the king’s real-life tactics, such as consolidating territorial gains by building road networks, postal networks and a professional army.

The Persian King of Kings fares better than the historical Gandhi, who as leader of a post-Second World War India takes on a trigger-happy foreign policy stance with the country’s nuclear arsenal. Originally thought to be an inside joke between developers which was accidentally left in, it turns out it’s always been intentional.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.