The French bookstore that celebrates immigrant history

Tucked away in the suburb of Nanterre, west of Paris, a new bookshop has quickly made its mark, not least on its mostly immigrant community.

Sociology graduates Halima M’Birik and Elsa Piacentino said they took a gamble, launching their business, in March last year, in the unlikely location outside of the main city.

“People keep saying, ‘why did you open your bookstore here?'” says Halima M’Birik, 34, who met Elsa Piacentino, also 34, when they were both students at the university of Nanterre.

“But in the neighbourhood, the bookstore was a godsend. It’s been two years since there had been a bookstore in town,” M’Birik tells Middle East Eye.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

What’s in a name?

The choice of location, but also the name, has been a source of intrigue for many. El Ghorba Mon Amour, a combination of Arabic and French, translates to Exile, My Love, and it’s the first word especially that piques the interest of locals. An emotional term for many immigrants, the word "exile" recalls feelings of nostalgia for a previous homeland, often mixed with loss or trauma.

“One woman started to cry when she saw the word [El Ghorba]. She came in and said, ‘Thank you. Thank you for remembering our parents, for remembering their story.’ She knew right away what the name stood for,” says Piacentino.

It was at university that M’Birik and Piacentino first encountered the term El Ghorba, through Algerian author Abdelmalek Sayad’s (1999) book La Double Absence (The Suffering of the Immigrant), which examines the intricate dichotomy between emigration and immigration.

“I’m not from a family of Arabic speakers, so the term has no personal connotations for me whatsoever,” says Piacentino.

“But when we discovered Sayad’s writings, and particularly his account of the immigrant from Kabylia [in Northern Algeria], we naturally made the link between sociology, the history of immigration, and the history of the city of Nanterre."

The second half of the name, Mon Amour, is derived from the 1959 French film Hiroshima Mon Amour.

“To us, it echoed the notion of El Ghorba, and the contrasts we wanted to highlight. Because the exile of El Ghorba is an experience of suffering but also of life, of possible encounters and hope,” M’Birik says.

“The film also explores ideas of impossibility… of speaking about some things, and that of remembering in the wake of trauma. This was obviously connected to our work on ideas of memory and struggle.”

A space for stories

It’s themes like this that were the driving force behind their chosen location. M’Birik and Piacentino were undecided on how they would continue their work towards social change - while students they had been active in the 2006 protests in France, opposing government attempts to deregulate labour, and in the creation of the RUSF (University Network Without Borders) to help foreign students get resident cards.

But they were certain they wanted to create “some sort of space” in the public housing district of Provinces Françaises.

“We didn’t know what shape our project would take at the time, but we did know where. That was what mattered,” Piacentino says.

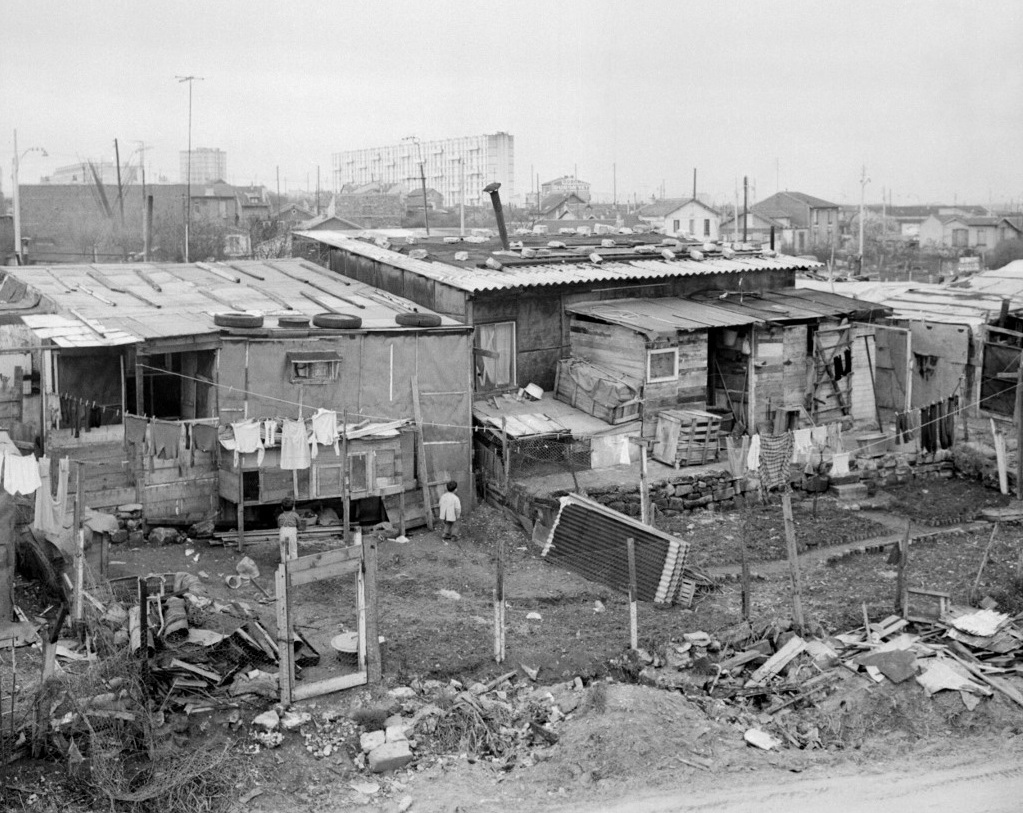

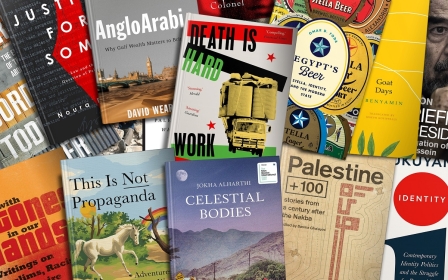

Offering more than the usual novels or great names in literature, the store includes books by French writers Faiza Guene’s La Discretion, Vehlmann Fabien’s Le Dernier Atlas and Vivants by Mehdi Charef, an Algerian author who lived in the bidonvilles (shantytowns) in Nanterre.

Because it is stories like these, of parents and grandparents who have experienced exile but whose stories are lost if they aren't passed on, that are indispensable in keeping memories alive for younger generations to learn about the culture of their heritage.

“We wanted to put the concept into practise in our bookstore. To make it a place for remembering past struggles, for remembering those stories and the difficulties of transmission.

“We wanted the name of the store to contain all of that. In La Double Absence, Sayad says that the impasse linked to exile can only be left behind through political existence,” M’Birik says.

Regenerating readers

Their commitment to promoting books and neighbourhood solidarity began in 2012. For three years they regularly held a bookstall near the Nanterre subway station exit.

“We didn’t want to wait until we had an actual place, [so] we founded an association and started holding our open-priced book sales. It was our way of meeting people,” M’Birik says.

“We organised neighbourhood parties and local events too, with the help of Nanterre’s extensive network of local associations. So, when our store finally opened, everyone was like ‘You did it! You opened your store!’ They were all waiting for us.”

Their venture has come on the back of a government-led regeneration project (2014-20) which has seen the University subway station renovated. Construction on a new shopping centre is being built and a number of office and apartment blocks have gone up around the older public housing units, which have also undergone a transformation.

Although there are some efforts to support and engage vulnerable communities in this neighbourhood where many of the area’s more deprived population live, permanent initiatives like a retail outlet targeting the local community are few and far between.

Everyone welcome

The idea of a hybrid Arabic-French store name did not sit well with everyone, especially with one financial backer who conflated it with a faith-based project.

In recent years tensions have escalated in France over the place of Islam and Muslims in the country, with President Emmanuel Macron's government presenting a strict draft law aiming to tackle "Islamist separatism". There are fears this could contribute to the conflation between Muslims and terrorism in a country already rife with Islamophobia.

However, for M’Birik and Piacentino, they were making a strong political statement with their bookshop.

“Some investors, especially one of the bankers, felt it should be just another bookstore, a place for rich people and whites. [They said] it would never attract people living in a working-class neighbourhood, meaning the poor and the non-white. It was an incredibly problematic vision,” says Piacentino.

'How can you defend the idea of universal access to culture when there are no spaces dedicated to mainstream culture, when what you do is inaccessible to most?

- Halima M'Birik, co-founder of El Ghorba Mon Amour

“They told us we were making a twofold strategic error, by opening our store here and choosing a half-Arabic name,” she says.

Despite the response, the two friends stuck to their original idea and opened the bookstore selling general books rather than activist literature.

“It’s something we gave a lot of thought to. The fact that there aren’t any bookstores in Nanterre today also influenced our decision,” Piacentino says.

M’Birik, who used to work in Nanterre’s public library, adds that their book selection was intended to be as inclusive as possible.

“We have to do away with the elitist mindset. A trade books retailer that sells mainstream literature is a way of encouraging people. Everybody here is welcome.

"How can you defend the idea of universal access to culture when there are no spaces dedicated to mainstream culture, when what you do is inaccessible to most?” she says.

“Taking this kind of stand would only replicate and reinforce patterns of exclusion and division. Opening a non-specialised bookstore was our way of saying that everyone is welcome. The idea is simple really - to reach as many people as possible".

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.