Dinner with the enemy: How Egyptian drama El-Daif sparked a row over Islam and the hijab

In a highly polarised society, what happens when a member of the family invites someone from the other side of the social divide for dinner?

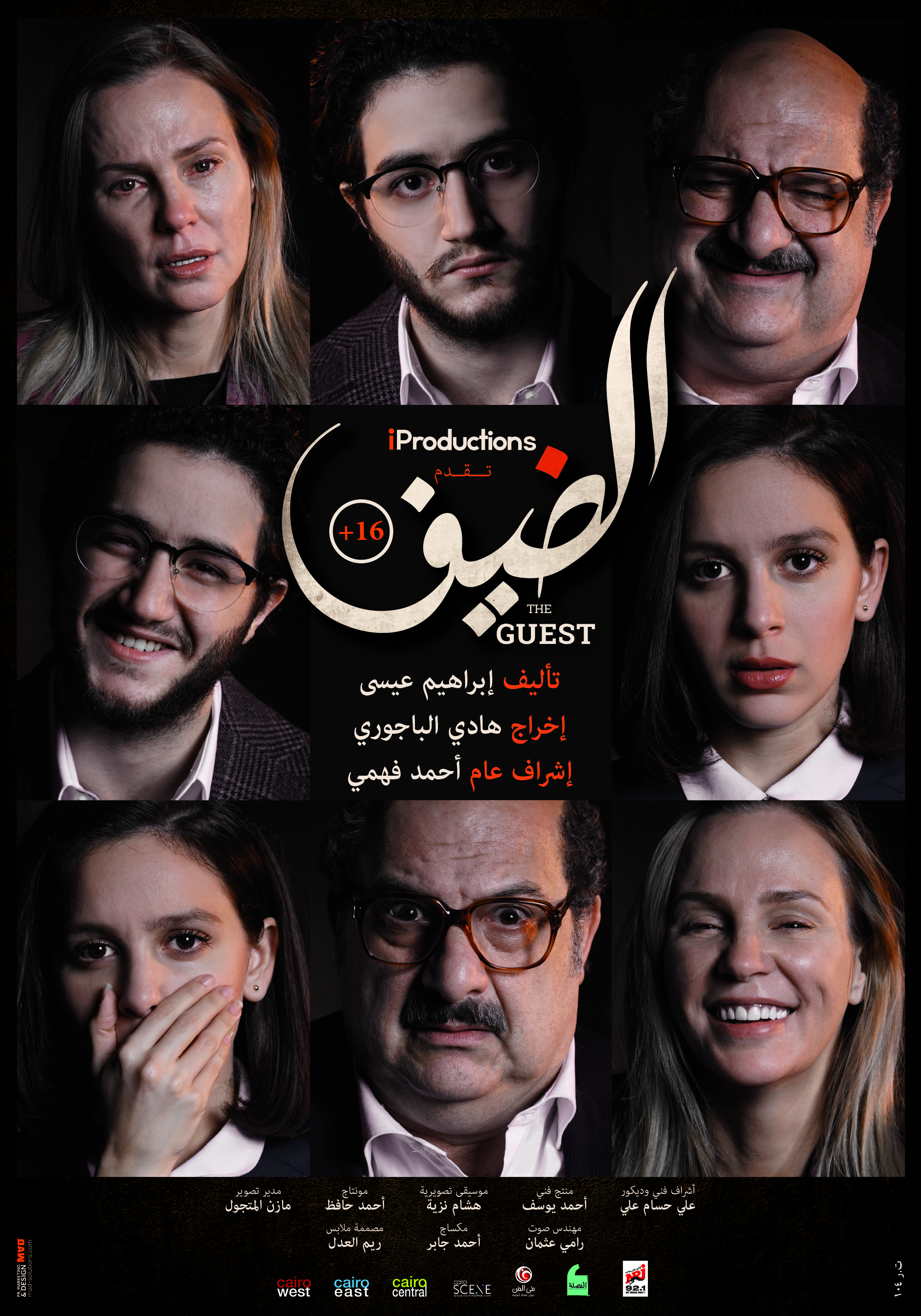

That is the subject of El-Daif (The Guest), a new drama written by journalist Ibrahim Eissa and directed by Khalid El-Bagoury that has become both a box office and a critical hit in Egypt, while at the same time attracting controversy.

'The idea of the film is quite outstanding, presenting Egyptian cinema in a new shape'

- Tarek El-Shenawy, critic

El-Daif starts with a dinner invitation as Farida (played by Jamila Awad) introduces a religiously ardent young man named Osama (Ahmed Malek) to her intellectual father, Dr Yahia El-Tigani (Khalid El-Sawy).

What unfolds is a heated discussion about religious discourse between the younger and older man. The suitor, who appears to be highly influenced by Islamic fundamentalists, keeps engaging in arguments with Yahia, which are mostly won by the wit of the latter.

But the clash later takes a violent turn as the true motives of Osama are revealed.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

El-Daif is set mainly in the house of Yahia, who in many ways echoes the character of writer Eissa, a journalist and intellectual known for his outspoken writings on religion.

Eissa is no stranger to controversy. Before El-Daif, he caused a stir with his first screenplay, for Mawlana (Our Grand Sheikh), about modern Muslim televangelists as well as the relationship between religion and the state.

Before its release in Egyptian cinemas, El-Daif won the Audience Award at the Estonian Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival in December, although it has received mixed reviews in Egypt.

"The idea of the film is quite outstanding, presenting Egyptian cinema in a new shape," Egyptian critic Tarek El-Shenawy said.

"The producers did not seek financial gain. Rather, they have sought to create an artistic experience. I only blame them for setting the film in a single location; but in a nutshell, the distinguished performance of the four main characters sort of surpassed this point."

Audience members spoken to by Middle East Eye agreed. "El-Daif has very well depicted taboos never discussed before in Egyptian cinema, showing how Islam is misinterpreted as a religion that forces a woman to cover herself from head to toe," said Nagwa Ali, 40, an accountant, as she was leaving a Cairo cinema.

"The argument over hijab [women’s Islamic veil] in the film is very convincing, calling on people to think rather than just to be told what to do."

But other critics say the film is long-winded and static, although praising it for tackling taboo subjects otherwise ignored in Egyptian cinema.

The attacks begin

In the film, Yahia faces blasphemy charges due to his views about his interpretation of Islam and its teachings that have appeared in his books and articles. His life is at risk, which leads the government to assign policemen to protect him and his family against extremists.

Ironically, the fierce debates and controversy portrayed in El-Daif are mirrored in real-life arguments around the film, leading to calls for it to be banned.

By questioning the credibility of old and contemporary Islamic scholars and their interpretation of religious rules, especially regarding the hijab, El-Daif has stirred the wrath of lawyer Samir Sabry, who has filed an urgent lawsuit before a Cairo court against Eissa and has called for the film to be banned.

Sabry is a controversial lawyer well known for filing legal cases against high-profile individuals for allegedly breaking indecency laws. In an interview with The New York Times in January 2018, he said he has filed more than 2,700 lawsuits over 40 years, targeting actors, clerics, politicians and belly dancers.

"It is clear that there will be grave damages if the film continues to be screened [in addition to] the bad impact it [could] leave in the hearts and beliefs of Egyptians," Sabry said in a media statement.

The first court hearing will be held on 23 February.

Religious ire

Not only did El-Daif stir the outrage of Sabry, it also angered Islamic scholars, including Khalid El-Gindi, a prominent preacher and member of the Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs.

"Six religious institutions including Al-Azhar [the highest Islamic authority in Egypt and the region] have stipulated that hijab is a heavenly order. Nevertheless, Eissa comes with his film to simply try to convince people otherwise," El-Gindi said angrily in a telephone interview with TV host Sayed Ali broadcast on Egyptian Al-Hadath Al-Youm satellite channel.

El Gindi also upbraided the Egyptian censorship authority which, although it took a few months to approve the film, surprisingly did not cut any scenes.

"It's a real disaster. We have a censorship authority that does not care about the Quran being misinterpreted and misquoted ... and sheikhs [who don't defend] their religion," El-Gindi said.

In the film, Eissa sums up the ideologies he has been advocating in his writings and TV shows over the past two decades. "The story of El-Daif is derived from the Egyptian and Arab reality, from prevailing extremist thoughts and ideologies and from terrorism," Eissa said at the premiere.

"We have always faced terrorism with thought. Rather, we [now] need to face it with art."

How the hijab stokes anger

El-Daif avoids the stereotypical image of a religious fanatic, introducing a handsome light-bearded young man dressed in an elegant outfit who comes from a well-bred family and who has studied engineering in the USA.

He has managed to influence the intellectual's daughter to the extent that she agrees to wear the hijab despite her liberal upbringing.

Many women in Egypt wear the hijab for social rather than religious reasons, submitting to social and family pressures while also seeking to avoid sexual harassment. However, the attire does not protect women from unwanted attention and abuse, as women who have spoken to MEE confirm.

Verbal harassment never stopped after me wearing the hijab

- Heba Medhat, student

"Verbal harassment never stopped after me wearing the hijab, despite the words of encouragement I heard from my family to put it on, which made me insist on taking it off afterwards," Medhat said.

"In many communities in Egypt, especially lower and middle classes, you find women wearing the hijab only on the street and remaining without it in the presence of total strangers when they are at home! Is that what the so-called Islamic teachings said?"

Egyptian feminists and liberal thinkers have their own explanation of the hijab as being often associated with the rise of the conservative Saudi Wahhabi doctrine that emerged in Egyptian society in the mid-1970s.

In his book, Whatever Happened to the Egyptians, the late intellectual Galal Amin argued that the hijab was mainly introduced to Egypt through the thousands of Egyptians who migrated to Gulf countries, especially Saudi Arabia, to work during the 1970s and 1980s.

Enlightening the 'suitor'

Throughout the course of the film, the audience hears views on several issues that have repeatedly been raised by militants in Egypt since the 1970s, following the advent of Islamist movements in the country.

Among these is whether the hijab is an optional outfit for Muslim women, rather than an obligation stipulated by Islam as Al-Azhar scholars and as conservative Salafists advocate.

While Islamic scholars believe that the hijab is considered a religious obligation, symbolising the submission of women to God's orders, Eissa, through his protagonist, El-Tigani, argues that the Quran has never said this explicitly.

"No single verse in the holy Quran condemns women for not wearing the hijab or threatens to throw them in hell for this reason," El-Tigani argues, addressing Osama.

"Son, until the 1970s, the daughters and wives of Al-Azhar sheikhs were not veiled. Neither was the wife of the Muslim Brotherhood leader," El-Tigani added in an attempt to enlighten the so-called suitor.

Modern marriage is another of the themes El-Daif depicts, as the future mother-in-law, portrayed by Shereen Reda, harbours her own secrets which shock the narrow-minded Osama.

Eissa: Art is to stir the mind

In the first six weeks of screening, El Daif took around seven million Egyptian pounds (about $400,000) and remained in third place at the Egyptian box office. It is still showing at most Egyptian cinemas.

"Deals are underway to screen the film in a number of Arab and European countries," said an official at the film's production company, iProduction.

Responding to the huge reaction to the new film, Eissa wrote on Twitter: "I'm proud of the views liking the film, and even the arguments [raised] around it, or those disapproving or criticising it. This is the job of art, to address the conscience and stir the mind."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.