Iran: 16th century folio from Book of Kings set for auction in London

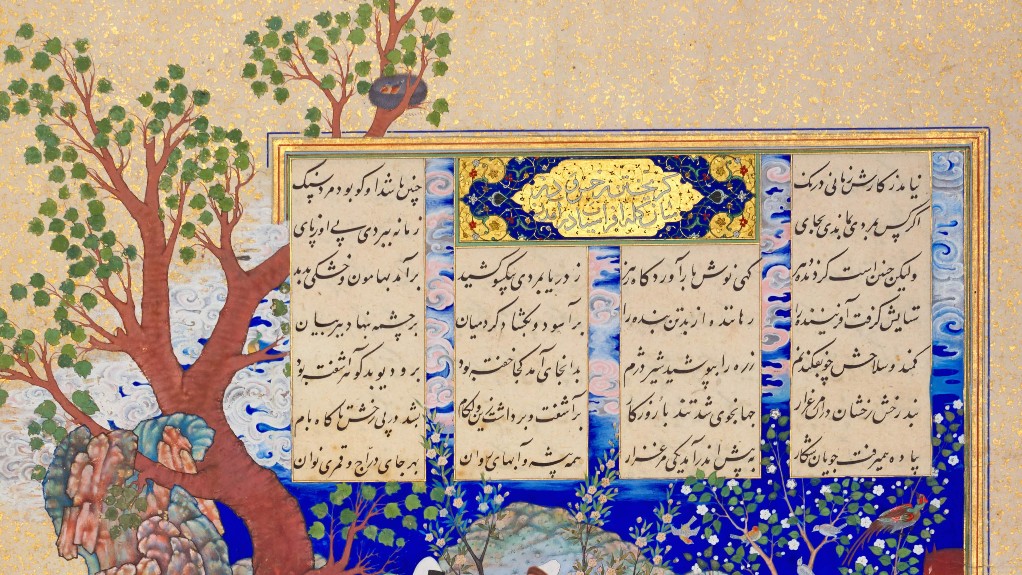

Flecked with gold and still boasting an array of magnificent hues, the rare 16th-century folio awaiting auction is unmistakably regal. And no wonder: it was once inside an edition of the Iranian Shahnameh, the Book of Kings.

Now the masterpiece is set to star in the Arts of the Islamic World & India sale held at Sotheby’s, London on 26 October, carrying an estimated price tag of £4m-£6m ($4.52m-$6.78m). Such a value is to be expected: this folio was not just from any Shahnameh, but rather from the copy commissioned by Shah Tahmasp - a manuscript generally recognised as being one of the finest works of art in the world.

Consisting of over 50,000 rhyming couplets, the original Shahnameh narrates the lengthy history of the Iranian people, spanning from the mythical beginnings of the world, through heroic stories and fierce rivalries, up to the historical invasion of the Muslim Arabs in the 7th century.

For centuries it has been seen as the ultimate guide for Iranian kings and princes, providing direction on how to reign over a population. Consequently, rulers of Iran have often commissioned their own copy of this Book of Kings.

Origins of the manuscript

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The great epic was first commissioned in 977 and was composed by Abu’l Qasim Ferdowsi, who was inspired by the 1,000 verses of Abu Mansur Daqiqi - a 10th-century poet murdered by his slave.

The major undertaking took Ferdowsi 33 years to complete and was finally finished in 1010.

Unfortunately for the poet, however, during this time dynasties changed. When he began, the Iranian lands were under Samanid rule, and emphasis was placed on protecting the heritage of the territory and its people.

By 1010, however, the lands had come under Ghaznavid rule. The Ghaznavids were of Turkic origin, and their interest in the history and language of Iran was considerably less. As a result, the Ghaznavid Sultan Mahmud paid Ferdowsi far less than agreed.

Ferdowsi died before any amends could be made, but his feelings about the snub were summed up in verses he wrote about the sultan:

“Long years this Shahnameh I toiled to complete

That the King might reward me with some recompense meet

But naught save a heart wrung with grief and despair

Did I get from those promises empty as air.”

The epic, however, has never lost value; it has always been treasured by the Iranian people. Written in classical Persian - rather than the favoured literary Arabic - and recounting the stories of the kings and heroes of ancient Iranian dynasties, the Shahnameh is seen as the protector of the Persian language and the very definition of the Iranian people.

Compendium of stories

The Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp, from which the folio currently up for auction originates, is thought to have been commissioned in the early 1520s by Tahmasp’s father Shah Ismail, the founder of the Safavid Empire.

“In fact, Ismail’s obsession with the great epic started much earlier, as he borrowed names from it for most of his sons, including Tahmasp,” Dr Firuza Melville, director of research at the Pembroke Shahnameh Centre, tells Middle East Eye.

Rather like the poem itself, work on creating the manuscript spanned many years and so was completed during Tahmasp’s reign - hence its name.

That the commission took so long is unsurprising; comprising 759 folios of text and 258 paintings, each page has been created from specially crafted paper enhanced with gold-speckled borders and illuminations.

What’s more, the layout - from the number of verses and columns included, to the decision on the scene depicted and its balance with that of the opposite page - had to be determined for every individual piece and overseen by an artistic director.

'For an Iranian to be familiar with Ferdowsi’s epic is more than for an Englishman to be familiar with Shakespeare’s Hamlet'

- Dr Firuza Melville, director of research

With the manuscript having been produced in the royal atelier in Tabriz where only the very best artisans were called to work, it is believed that Sultan Muhammad, one of the most influential artists of the period, may have been taken on this responsibility.

The folio in question has been attributed to the son of Sultan Muhammad, artist Mirza 'Ali. It is one of six folios thought to have been painted by the second-generation artist.

According to Melville, the Shahnameh has been a cultural symbol for Iranians for centuries, if not millennia.

“For an Iranian to be familiar with Ferdowsi’s epic is more than for an Englishman to be familiar with Shakespeare’s Hamlet or an Italian with Dante’s Divina Commedia,” she says.

Gifted as a peace offering

Despite the sheer effort put into producing one of the world’s most luxurious books, it did not remain in Iran long. In 1568, the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp was given away.

Gifted to Ottoman Sultan Selim II to mark his accession to the throne, it arrived in Edirne together with an array of porcelain, textiles, and silk carpets carried by a procession of 34 camels.

Why such a beautiful and expensive copy of such a significant epic was passed onto a different dynasty entirely is mainly down to two reasons.

Not only had Shah Tahmasp’s interest in art and literature decreased greatly as he became more religious, but there were fears of an Ottoman invasion. A treaty had been signed during the reign of the previous Ottoman sultan, Suleiman, however whether Selim II would maintain it was another matter. The gifts, including Tahmasp’s wonderful Shahnameh copy, were perhaps an offering of peace.

“By gifting this manuscript to the new sultan, Tahmasp was killing two birds with one stone,” says Melville. “He was opening a new page in the diplomatic and political relations with their constant rivals and enemies, the Ottomans, and saving himself from temptation of such a luxurious piece of art and literature which he refused to appreciate.”

Unbound, sold and distributed

The history of the Tahmasbi Shahnameh does not stop in Turkey, however.

While it remained in the library of Topkapi Palace - the imperial residence of Ottoman sultans - for more than three centuries, by 1903 it had made its way to Paris and into the collection of Baron Edmond James de Rothschild.

In 1959, the Rothschild family sold it to Arthur Houghton Jr, who would later become the president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The fate of the 16th-century manuscript changed dramatically in 1964, when it was unbound to allow a Harvard curator to photocopy the pages. It would never be rebound.

The owner, Houghton, decided that it was time to disperse the separate folios, gifting some to museums, including the Metropolitan, and selling others. It was only following Houghton’s death in 1990, that the dispersal stopped.

Four years later, in 1994, the remaining pages were sold back to Iran in a covert operation. Kept under wraps for fear it might cause uproar, a deal was struck: in return for the incomplete Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp, Iran would give the Houghton family Willem de Kooning’s painting Woman III, estimated to be worth $20m.

A trade like this was necessary; not only were official diplomatic relations between the countries still tense and sanctions still a possibility, but Iran was also short of hard currency. Examined by experts to ensure authenticity before being loaded into nine boxes in front of witnesses, the partial Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp arrived back in Iran more than 400 years after it first left.

The particular folio being auctioned by Sotheby’s in October was first sold by Houghton in 1988. It depicts the hero Rustam recovering his horse Rakhsh from the herd of rival Turanian Shah Afrasiyab.

“Rustam gets thrown into a river by the div [demon] Akvan, and Rakhsh runs away, joining a royal herd which belongs to the Shah of Turan. In this folio, the artist shows the moment when Rustam, after his miraculous survival, appears in the meadow and sees his beloved Rakhsh among the horses of Shah Afrasiyab,” says Melville.

“Presumably, he is the red chestnut stallion: this can be a reference to the etymology of the name Rakhsh which meant the colour red and was most likely borrowed from the Soghdian language. He is the only one who is covered with an exceptionally ornate, bright turquoise green and ultramarine blue saddle.”

With its superior artistry and exquisite calligraphy, one small folio brings an ancient world of heroism and mythology to life. Imagine, then, how wondrous a whole series of these folios would have been. That was the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.