Baghdad's House of Wisdom: Uniting East and West to pursue knowledge

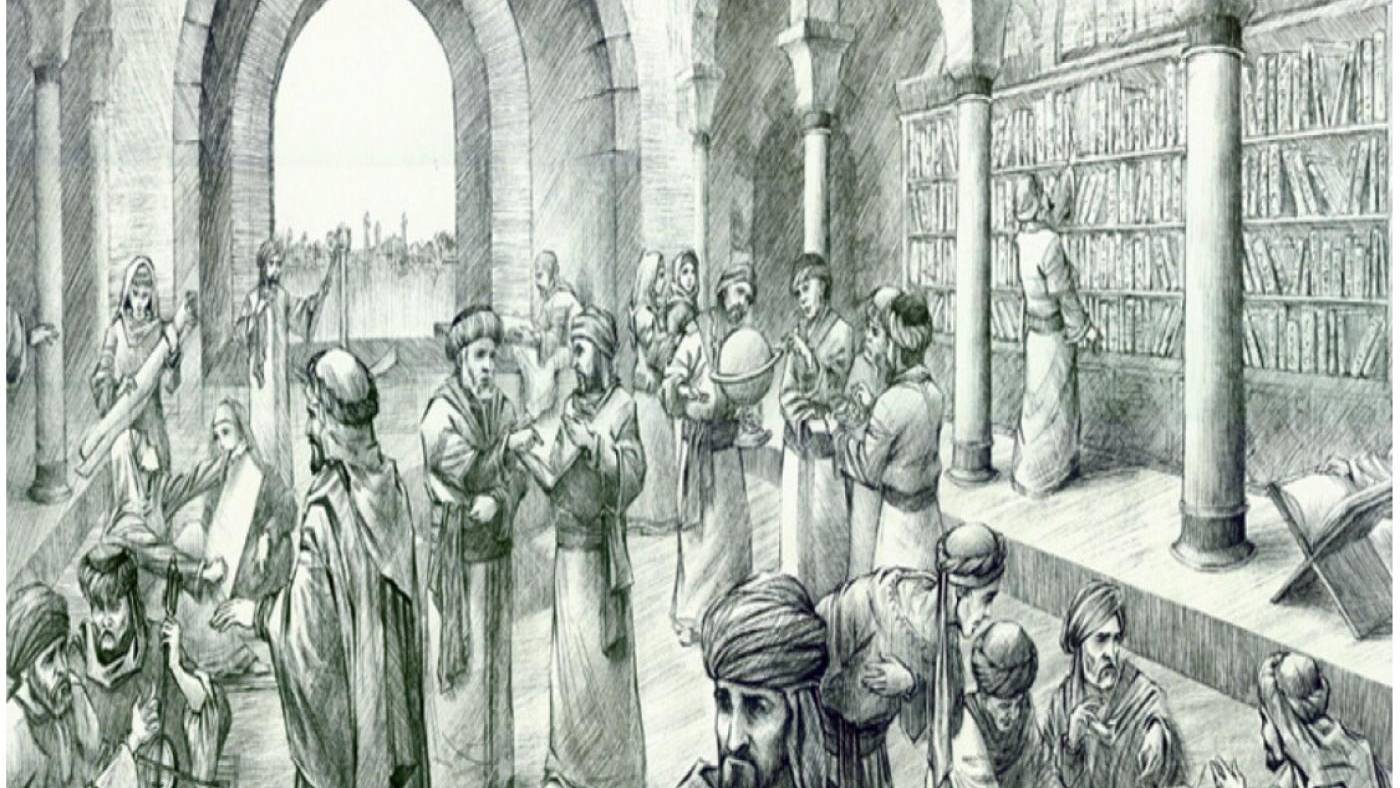

In eighth-century Baghdad, the Abbasid Caliphate took a momentous decision to found a library dedicated to preserving knowledge from across the world, known as Bayt al Hikmah, the House of Wisdom.

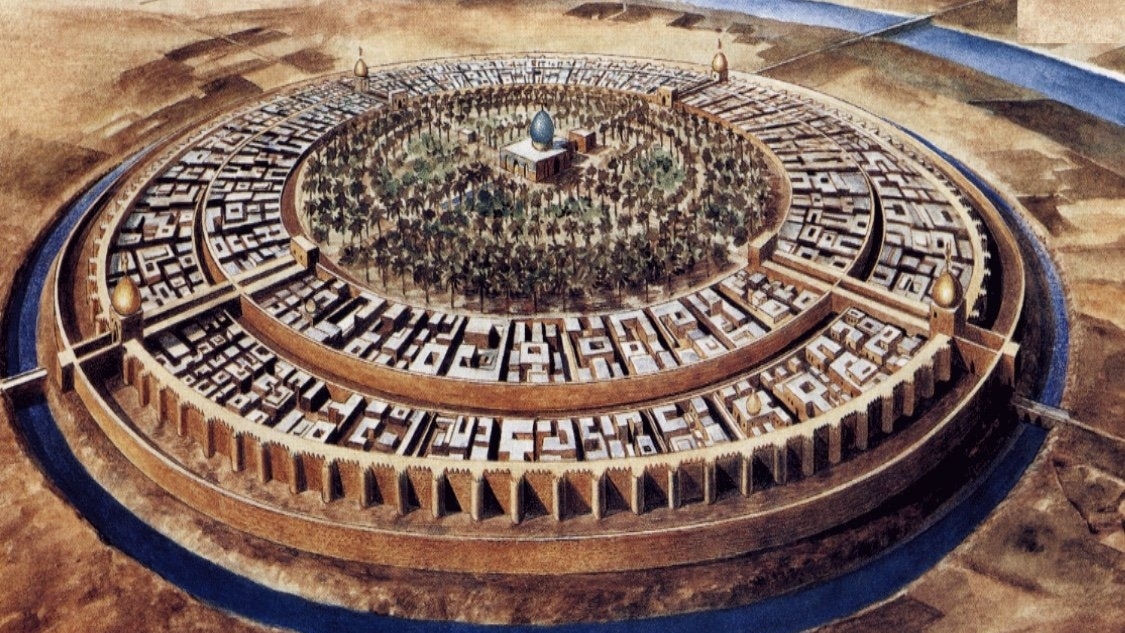

Inspired by the ancient Museum of Alexandria (Mouseion), the project was envisaged during the reign of the Caliph Al Mansur (754-775) as a simple repository of books, the Khizanat al-Hikmah (Library of Wisdom), but it would expand, under the rule of Harun al-Rashid (765-809), into a flourishing academic centre.

It is said that within its walls, the theologian, Al Jahiz, wrote his pioneering work, The Book of Animals, and that Ali ibn Isa al and Khalid ibn Abd al-Malik obtained a measurement that enabled astronomers to calculate the circumference of the Earth.

The eighth-century mathematician al-Khwarizmi (who introduced what later came to be known as Arabic numerals), the astronomer Yahya ibn Abi Mansurh, the philosopher al-Kindi, and the mystic al-Hallaj, were all regular patrons of the library.

Rashid was keen to make Baghdad a centre of intellectual growth and discovery and a flourishing home of the arts.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Immediately upon taking power, he commanded his vizier Yahya al-Baramika to transfer part of the palace’s private library into a public space.

Before that decision, the works were exclusively reserved for court scholars, however now the library could be accessed by general public.

What was now known as Bayt al-Hikmah (the House of Wisdom) soon attracted scholars from far and wide, and rapidly expanded to include a translation house, an observatory, and accommodations for visiting scholars.

In Arabic, the term bayt (house) refers to a “covered space”, contrary to dar which refers to a complex comprising several bayt.

Therefore, the House of Wisdom at the time of Rashid was called Bayt al-Hikmah as it was comprised of a single building.

But Rashid’s eldest son, the seventh Abbasid caliph, al-Mamun (786-833), had greater ambitions for the building.

Adept at the sciences since his early childhood, he had extensions built for each of the house’s different branches of knowledge, where scholars from around the world came to exchange knowledge.

Thus, Dar al-Hikma was born, and Baghdad, known then as Madinat al-Salam, became a hub of intense intellectual activity.

Al-Mamun: A patron of sciences

Al-Mamun’s dedication to collecting texts and expanding the repository of classical knowledge earned him the nickname “the sage of Baghdad”.

But the great humanist also advanced the frontiers of knowledge by commissioning the translation of his trove of literary and scientific works into Arabic.

From Andalusia to China, al-Mamun implemented two different strategies. The first was to claim rare scrolls and ancient texts as war booty.

More than 800 works of Ancient Greek literature were thus procured under the terms of the peace treaty signed with the Byzantine Emperor Theophilus.

The second was to dispatch missions to emperors and other rulers throughout the empire to facilitate the gathering of valuable manuscripts, such as the 2nd-century astronomical treatise by the Greek scholar, Ptolemy, whose English name, Almagest, derives from its later Arabic translation.

Translation as a tool of transmission

The Abbasid caliphs’ appetite for knowledge was such that an entire body of classical scientific literature - including works by Aristotle, the Greek physician Galen and the Indian surgeon Sushruta - was translated into Arabic, thanks to the House of Wisdom.

One popular narrative holds that the impetus behind the translation movement was because of Al-Mamun’s encounter with Aristotle in a dream.

The philosopher apparently urged the caliph to preserve the knowledge of ancient civilisations by gathering classical literature and sponsoring translation.

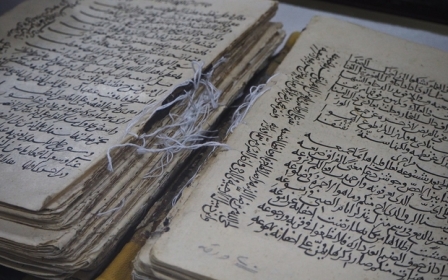

Works translated at the House of Wisdom include Aristotle’s books Rhetoric, Poetics, Metaphysics, Categories and On the Soul, as well as Plato’s Republic, Laws and Timaeus.

The primary working languages of the Baghdad academy were Greek, Syriac, Persian, and Arabic. However, translations at the House were subject to three conditions: translators had to be knowledgeable in the field of translation, to be fluent in at least two of Dar al-Hikma’s official languages, and to work from original sources only.

It was even said that translators were awarded the weight of each successfully completed book in gold. From that time on, Arabic was the international language of science and learning.

The doctor Hunayn Ibn Ishaq (1405–68), accompanied by his son Ishaq ibn Hunayn and his nephew Hubaysh, was one of the most important translators of Greek medical and scientific treatises.

Later, al-Mamun would appoint him head editor in charge of revising all translations at the House.

But Ibn Ishaq was not simply content with translating and editing works. Instead, he expanded the vocabulary of Arabic by introducing new scientific terms.

He took Greek words, such as "philosophia" that became "falsafa" in Arabic, and found translation solutions via what contemporary translators would call equivalents.

For example, to translate the word pylorus into Arabic, Ibn Ishaq refers to the word’s etymological meaning (guardian, in ancient Greek) and uses the word bawab (porter) in Arabic.

The Assyrian scholar Yahya Ibn al-Batriq (730-815) translated all the major works of the ancient Greek physicians, including Galen and Hippocrates. He also compiled the universal Kitab Sirr al-Srar, known in the West as the Secretum Secretorum (Secret of Secrets).

Additionally, each of the translations was annotated by scholars from the field in an effort to explain the sciences to the general public.

Abdullah Ibn al-Muqaffa (724-759) was another pioneer of literary translation sponsored by the House of Wisdom.

The father of Arabic prose, he translated and adapted a wealth of works from Persian, including his renowned Kalila wa Dimna, an adaptation of the ancient Indian collection of tales and fables Panchatantra, which would inspire the 17th-century French poet Jean de La Fontaine centuries later.

Period of decline

Following the death of Al-Mamun, the House of Wisdom entered a period of slow decline and would collapse for good with the arrival of the Mongols under Hulagu.

In 1258, the Mongol army ransacked the city of Baghdad and threw such a great number of manuscripts into the river Tigris that the waters ran black with ink.

Foreseeing the impending tragedy, the Persian astronomer Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201-74) saved several thousand manuscripts by moving them to the Maragheh Observatory in northwestern Iran, built by Mongol ruler Hulagu in 1259.

The memory of both the House of Wisdom and its larger incarnation Dar al-Hikma has since inspired a wealth of initiatives in both the East and the West, committed to carrying on the spirit of the pioneering translation house, including, most recently, the House of Wisdom - Translate, in Paris, launched by the French philosopher and academic Barbara Cassin.

This article was originally published by Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.