How Arbaeen fosters a common identity between Iraqis and British Shia Muslims

In early September, against the backdrop of deadlocked attempts to form a government and periodic civil unrest in Iraq, British Shia Muslims travelled to the southern Iraqi cities of Najaf, Karbala and Samarra, joining millions of others from around the world to commemorate Arbaeen.

The religious occasion marks the fortieth day of mourning of the anniversary of Ashura, the day on which Hussein ibn Ali, the third Shia imam and the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, was killed at the Battle of Karbala, nearly 1400 years ago.

Hussein had refused to pay allegiance to the new Umayyad caliph, Yazid ibn Muawiyah, who he believed was acting against the ideals of Islam. As Hussein and his family attempted to travel towards Kufa in modern day Iraq, they were surrounded by the Umayyad army.

Hussein’s camp was cut off from water supplies and almost all of the 72 male friends and family members who had accompanied him on his journey to Kufa were killed, while the women and children were taken captive.

The event played a formative role in the creation of the Shia identity, in which opposing injustice and oppression has become a key ideal.

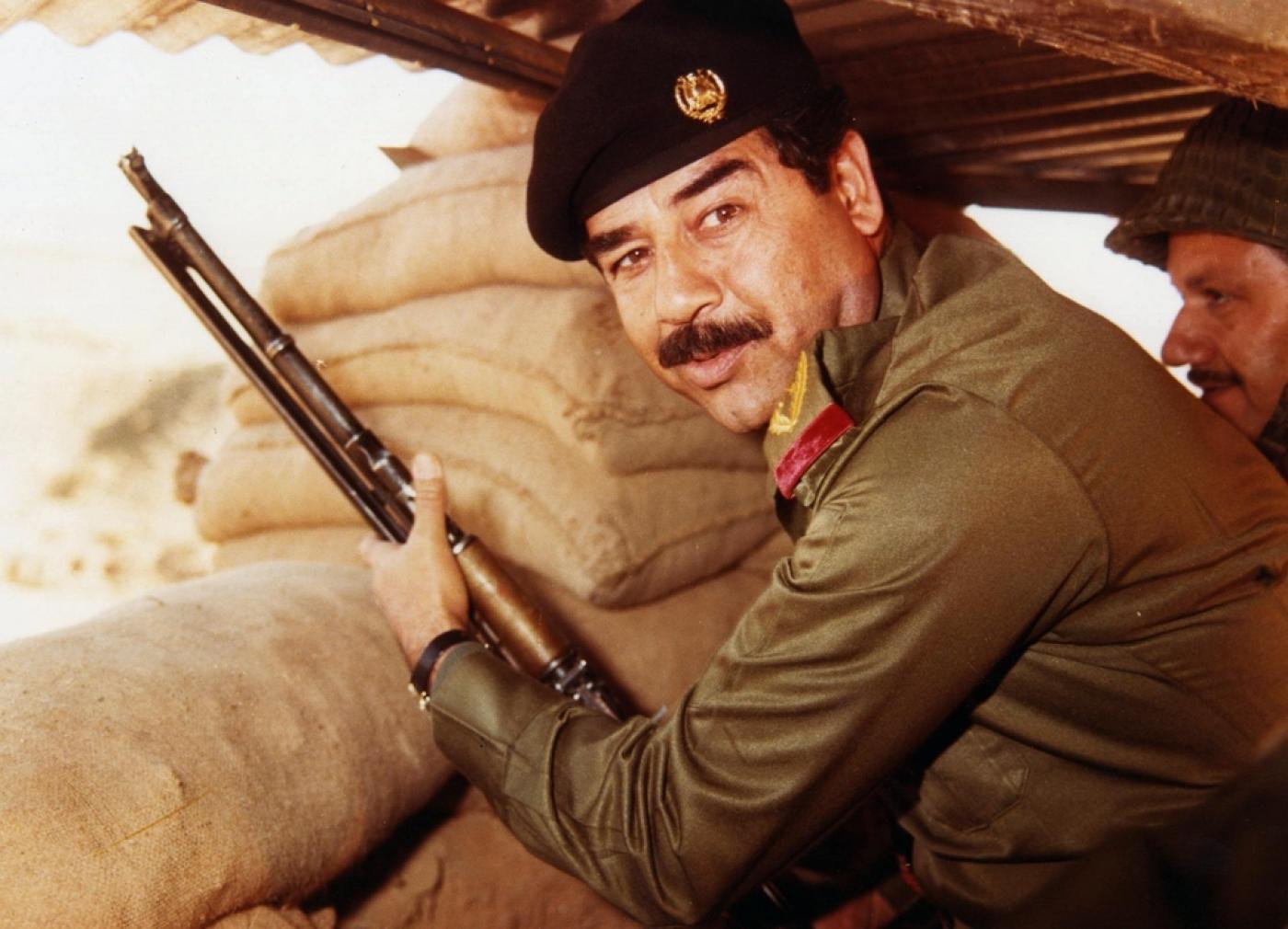

Since the fall of former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein in 2003, there has been a resurgence of previously restricted Shia mourning rituals. Karbala, Najaf and Samarra have drawn a steadily increasing number of visitors, and now play host to Islam’s largest annual pilgrimage, known in Arabic as the ziyara.

In 2019, the number of pilgrims taking part in Arabeen commemorations reportedly exceeded 14 million. Even more are expected this year, despite the volatile political situation in Iraq.

Braving the risks

Since the escalation of the ongoing protest movement in Iraq, the UK has advised its citizens against all but essential travel to the country.

Even before the current unrest, however, British Muslims, alongside pilgrims from elsewhere, have travelled to Iraq despite the political instability and the threat posed by organisations like the Islamic State (IS) group, which targeted Shia Muslims in bomb attacks.

Nabeela Zaman, a British Shia of Bengali heritage, travelled to the southern shrine cities during Ashura in 2022.

“It’s not something I even looked at,” she said when asked whether the political situation made her reconsider her travel plans.

What drives her, and others, is the feeling that by visiting the shrines, they are serving a higher purpose.

Zaman said: “The ziyara is not like Hajj, it’s not an obligation. But I feel – and I think many feel – that when we go for ziyara, we’ve been called there by a higher power.

“For many, it is a once in a lifetime opportunity and that is why we don’t let anything stop us.”

That’s a sentiment echoed by British Indian Muslim, Mohsen, who spoke of an incident 2007, in which his tour group narrowly escaped an explosion.

“People were scared, but it didn’t stop us from coming back,” he said. “We have love for Imam Hussein. Nothing will stop us from coming back.”

The targeting of Shia pilgrims by IS and al-Qaeda members has in some cases made pilgrims more resolved to continue.

Discussing her experience of visiting the Hassan al-Askari shrine in Samarra in 2009, after it had been desecrated by al-Qaeda insurgents in 2006 and 2007, Nabeela Zaman said: “I remember how it felt, seeing the shrine like that. It makes you more determined to come back.”

“In 2017, there was no change in the number of pilgrims we took to Karbala,” said Romana, a volunteer with the UK branch of Spiritual Guides, a tour company organising pilgrimage trips to Iraq, adding: “Daesh [IS] was at the height of its power, and pilgrims were still committed to coming to Iraq”.

Historic dangers

The pilgrimage to Shia shrines in Iraq has long been fraught with risk for both locals and foreigners.

Under Saddam’s rule, foreign pilgrims were heavily monitored by the state. Fearing a Shia political revolution in Iraq that would mirror that of Iran’s, the Baathist government kept a watchful eye on all pilgrims to the shrine cities.

Yasmin, who travelled to Iraq extensively during the 1990s, recalled her experience in Karbala and Najaf, saying: “You were never allowed to be in the shrines alone. Two government guards were always watching you. You felt monitored. Even prayer books which contained pictures of the Marja (spiritual guides) were banned.”

British nationals who were not of Iraqi origin were also detained by Saddam’s government.

Mulla Asghar, a prominent figure in the global Khoja community, was arrested on one of his ziyara trips, where he was held in a Baghdad jail for three months, until international pressure forced his release.

Despite this, both under Baathist rule and post-Saddam Iraq, foreign pilgrims have remained comparatively insulated from the political and security threats faced by Iraqi citizens.

For Iraqis, the risks were much greater. Mulla Asghar spoke of meeting Iraqi prisoners who had been held at the notorious Abu Ghraib prison for over 10 months, charged with the crime of frequent visitation to the shrines.

Since the fall of the Baathist government, pilgrimages have grown in scale as fear around repercussions for Shia religious observance has melted away.

Given the religious and cultural significance of the shrines in Iraq, and the vital role religious tourism plays in Iraq’s national economy, significant measures have been taken to protect the pilgrimage routes, particularly for foreign visitors.

Many foreign pilgrims fly directly into Najaf, and those who fly to Baghdad are often provided with security until they reach the south of Iraq.

According to the British ziyara tour guides that spoke to Middle East Eye, the Office of Ayatollah Sistani will frequently provide private security for pilgrims who travel to Samarra, and the shrines themselves are protected by armed wings of various political groups in the country.

In a similar vein, Iraq’s energy crisis - in which widespread power cuts spark frequent protests in the summer months - has had a minimal impact on foreign pilgrims. Equipped with expensive private generators, local hotels do not experience the frequent power cuts that plague wider Iraqi society.

Connecting with Iraqis

The relative insulation from the Iraqi political climate enjoyed by foreign pilgrims has not precluded the development of strong ties between Iraqi citizens and non-Iraqi British Shia pilgrims.

The British Shia population, a significant proportion of which has South Asian origins, and remains ethnically and linguistically distinct from Iraq, finds itself increasingly connected to Iraq in more than just a religious capacity.

The Arbaeen commemorations carried out in the south of Iraq include an 80km walk from the shrine of the first Shia Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib in Najaf to the shrine of Hussein in Karbala.

Iraqis living on the road towards Karbala will open their homes to pilgrims, inviting them to rest in their houses.

Yasmin, who has attended the Arbaeen walk annually for the last decade, told Middle East Eye: “I’ve never experienced anything else like it. Whenever I go, it feels like I am coming home.”

The growing centrality of the Arbaeen walk, and Iraqi culture, in the commemoration of Hussein’s death is highlighted by the replication of the walk by communities in Britain.

This year, Hyderi Islamic Centre, a Shia mosque in London, recreated the Arbaeen walk in its neighbourhood, depicting the trajectory of the walk for those who were unable to travel to Iraq.

Walkers encountered different Mawkibs present on the route - these are stations that provide food, medical services and shelter to pilgrims on the route to Karbala, as well as traditional Iraqi food that is often served to pilgrims on the walk.

'I feel – and I think many feel – that when we go for ziyara, we’ve been called there by a higher power'

- Nabeela Zaman, British Shia Muslim

The effect of these experiences on the visiting populations is demonstrated by the extent to which fundraising for charitable organisations in Iraq has become a mainstay of the British Shia experience.

During Ramadan and Muharram, British Shia communities, most of which are non-Iraqi in origin, will fundraise to aid programmes in Iraq.

Particularly among the British South Asian Shia diaspora, fundraising for aid groups in Iraq will often take precedence over fundraising campaigns for aid in their countries of origin.

These funds are not channelled exclusively towards Iraq’s Shia community.

British charities such as the Zahra Trust have worked across Iraq, distributing food, heaters, and clothing to vulnerable communities, as well as supporting the building of water wells in remote locations.

Other British Shia Muslims have travelled frequently to Iraq in times of unrest to provide medical aid in the southern governorates during Ashura and Arbaeen.

Romana has travelled to Iraq annually since 2004 in order to provide medical assistance to those in need. Addressing the motivation behind her decision to offer such help in Iraq, Romana said: “We are connected to Iraq through our love for Imam Hussein, but it is also wider than that. Our love for Imam Hussein also connects us to this community.”

She emphasised that her support of the Iraqi population was not limited to one community but also extended to others that make up the social fabric of the country.

During the defence of Najaf and other shrine cities, members of other religious communities had fought alongside Shia fighters against Islamic State group.

Referencing the 2016 IS advance towards Najaf, she said: “I have worked with a lot of orphanages in Iraq. The parents of these children, who were not only Shia but from a range of faiths, fought IS, they defended Iraq, and they defended the shrines, because Ayatollah Sistani asked them to. Irrespective of their religious denomination, it is their right to expect support from us.”

Others who have participated in Arbaeen in the south of Iraq spoke of the unifying power of the ziyara.

“It’s incredible. You meet people from every part of the world. China, Indonesia, Pakistan, the Middle East… and you’re all connected,” said Yasmin. “You are connected because you are walking to the same place with the same objective”.

The British Shia connection to Iraq highlights a different manifestation of trans-national Shiism. In place of soft power harnessed by political groups and states in the region, this phenomenon demonstrates how shared faith facilitates connections, which transcend modern nation states.

Some of those interviewed by Middle East Eye did not wish to give their surnames

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.