Jews, money and antisemitism: How the hate myth was born

The American animated comedy behemoth Family Guy might not be the first thing you associate with an exhibition concerning antisemitism. But enter the Jewish Museum London during the next two months and you may find excerpts from the show drifting your way.

Walk into "Jews, Money, Myth", its current event, at another point and instead you may be greeted by South Park or Borat or political figures like Donald Trump or Nigel Farage.

All take their place in a video piece by Turner Prize-winning artist Jeremy Deller, which draws together footage – satirical as well as chillingly straightforward – demonstrating a long-established stereotype that shows no signs of going away: that Jewish people are greedy and that they love money above all else.

Bringing together manuscripts, prints, ceremonial objects, artworks and cultural ephemera including board games and costumes, the exhibition lays out a complex, 2,000-year history of stereotyping.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

It runs from the theological roots of associating Jews with money to the myths and reality of the medieval Jewish moneylender. The visitor is then taken into the world of modern commerce and capitalism, in which the lives of working class Jews are often obscured and antisemitic conspiracies about the world being run by a cabal of malign Jewish bankers continue to infect the political discourse from the United States to the Middle East and beyond.

Judas, silver and betrayal

The story begins, more or less, during the time of Jesus, and the fate of his disciple Judas Iscariot, who the Bible says betrayed Jesus to the Jewish chief priests in exchange for 30 pieces of silver.

Like Jesus and his fellow disciples, Judas was Jewish, but from the 12th century onward, he began to be transformed into a personification of all Jews at a time when many Jews in Europe were pushed into unpopular economic roles such as usury (lending money for interest), which the dominant Catholic church regarded as sinful.

This personification was not kind: Judas became known as the archetypal traitor, a symbol of greed and heresy. He was the man who stood on the wrong side of the Bible’s line: in the Book of Matthew, “it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God”.

Judas was attached to material wealth, not spirituality, wedded to this world rather than the world to come. Crude depictions of the disciple, who had been shown by others to be Jesus’s closest confidante, presented him as a ghoulishly Jewish caricature of evil and greed, complete with a money bag, bright yellow cloak and red hair.

Some aspects of his appearance have continued to have symbolic resonance. The colour yellow was used to distinguish Jews (and other non-Muslims) from Muslims in the Umayyad Caliphate, and Jews and Muslims were during certain periods required to wear distinguishing clothing in Catholic-dominated medieval Europe. The yellow star branded Jews as having betrayed Jesus, a branding that was re-introduced by the Nazis.

The jewel in the crown of the Jewish Museum’s exhibition is a beautiful, beguiling and far more complex portrait of Judas. Rembrandt’s Judas Repentant, Returning the Thirty Pieces of Silver (1629) shows the disciple trying to return the money he has taken in exchange for his act of betrayal.

Kneeling on the ground, his hands clasped together, scalp bloodied from tearing his hair out in anguish, Judas is tormented by what he’s done - and yet still his eyes seem to meet the money he has thrown to the ground. The deadly pull of the silver is not quite extinguished. The priests are unmoved. They refuse Judas. He leaves the temple and hangs himself.

A game of hate

In the medieval and early modern period, the figure of the Jewish moneylender was more often represented in a way that recalls the crude depictions of Judas with moneybag and red beard.

This was despite the fact that it was not only Jews who worked as money lenders, even though lending money at interest was sinful in Judaism as well as in Christianity.

The role was often taken on by Jews because the antisemitic societies they found themselves in brought forward little in the way of alternative occupation.

This concept of the Jewish moneylender in Europe, most famously embodied by Shylock in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice (first performed in 1605) and later by Charles Dickens’ Fagin in Oliver Twist (1839), is shown to be at the heart of associations between Jews and money, as artefact after artefact attests.

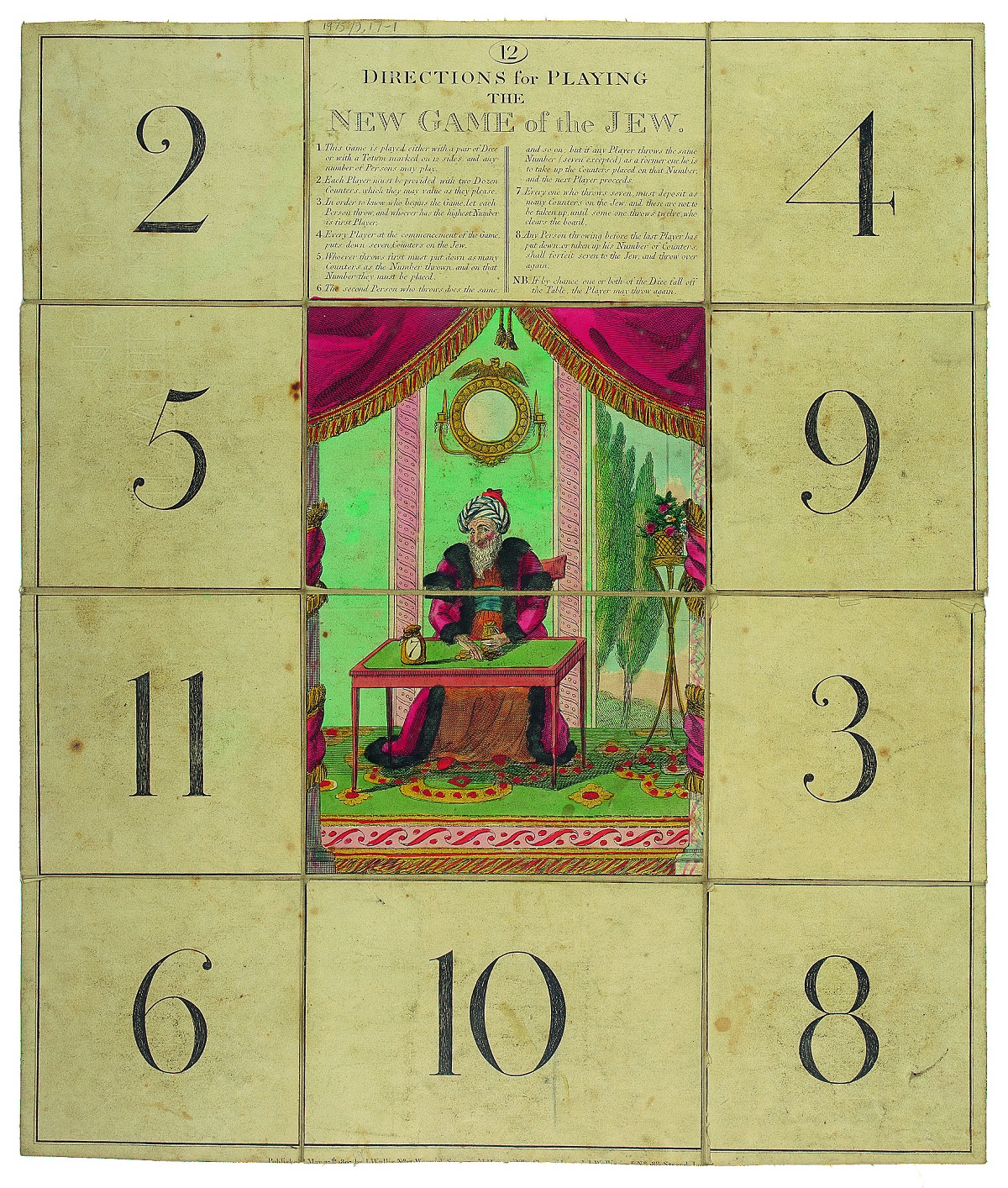

From 1807, a children’s dice game called The New and Fashionable Game of the Jew comes with an illustration of an old man in a turban, a stereotypical Jewish banker in fine robes hoarding his money, prepared to rip off all those good Gentile boys and girls with his tricky ways. Stephen Sondheim, the Jewish-American composer, owns a copy and describes it as the game that “taught kids to be antisemitic”.

A few years earlier, in 1798, Nathan Mayer Rothschild disembarked in London from Germany. The new arrival was to become phenomenally successful, establishing the first branch of the Rothschild family bank and going on to finance a series of British military campaigns.

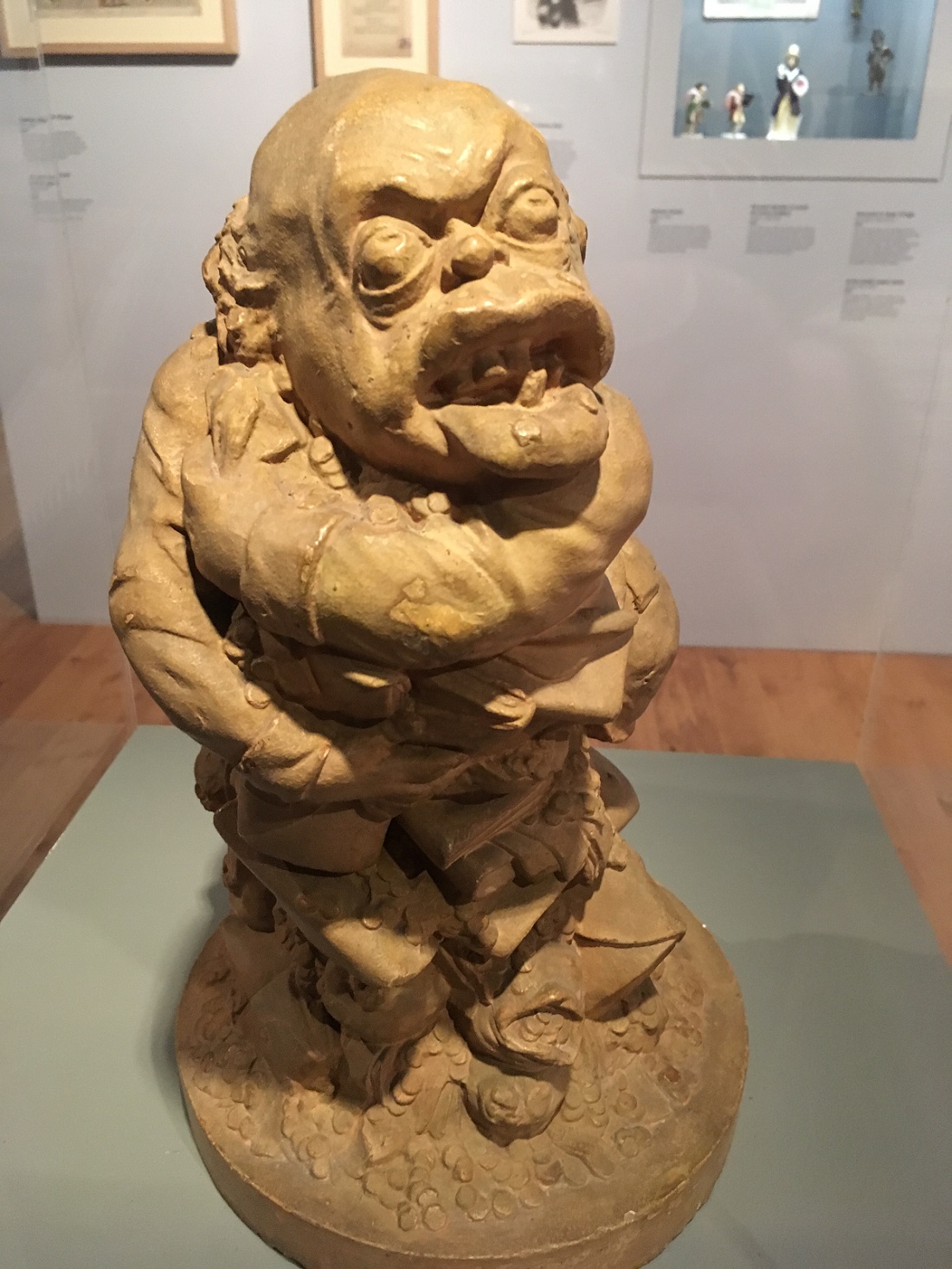

The sculpture of him by Jean-Pierre Dantan is one of many gruesomely antisemitic works of art on display at the exhibition, the Jewish banker shown as a grossly dehumanised figure, all rolls of fat, engorged lips and bulging eyes.

Rothschild’s rise to power started the theories of influence surrounding his family that continue today and which have proliferated on YouTube and social media.

The development of commerce in the 18th and 19th centuries transformed the economic status of some Jews, leading to the rise of two prominent and contradictory stereotypes: that of the Jewish banker and that of the Jewish beggar.

Anxiety and disgust with the cruelty of capitalism could too easily be distorted into antisemitism, with figures like Rothschild used as representatives of a system that ground down millions of people not simply because they were powerful capitalists, but because they were Jewish. Some of those victims of capitalism were, of course, Jews themselves and often economic migrants living precarious lives.

But stereotypes are not rational: at the same time as Jews were being shown as grotesquely wealthy capitalist pigs, they were also being depicted as hopelessly devious beggars, leeching off society.

Race and capital

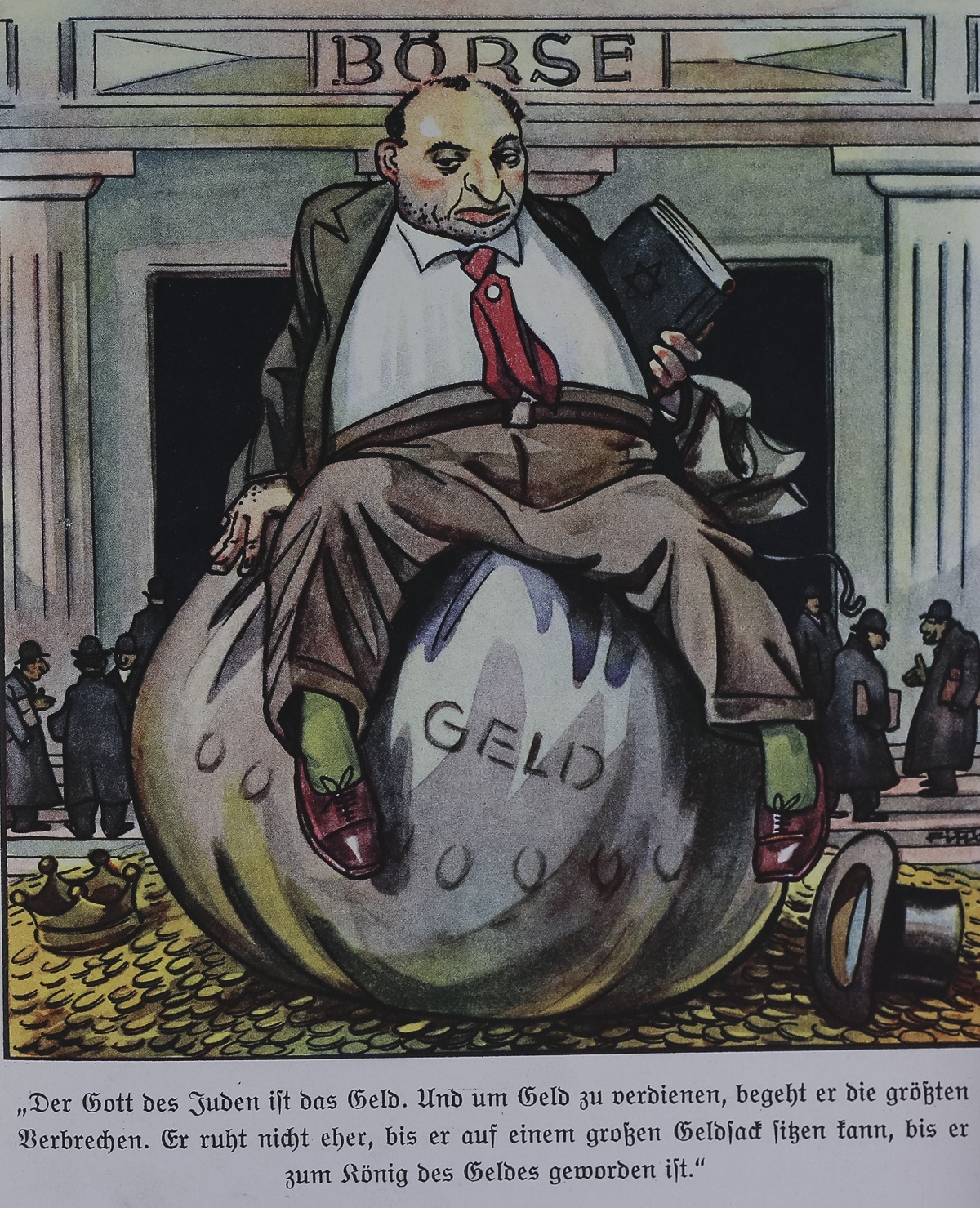

As the spectre of communism came to haunt Europe, the same trick was pulled: Jews were rich capitalists yet were also devious Bolsheviks, intent on overthrowing the good and natural order of things.

In 1930s Germany, the Nazis made headway with both these stereotypes as they rose to power, decrying communism as another form of Jewish conspiracy while in the same breath assaulting Jews for taking bread off the table of good honest Aryan folk.

Nor was it just in Germany: in 1933, an entry from the Oxford English Dictionary listed one of the definitions of the word “Jew” as “to cheat”.

These myths and stereotypes persist. Arguments about capitalism can still veer into racist territory. Justified criticism of the state and government of Israel can still drop horribly into conspiracies about Jewish power and wealth.

The relative financial success of Jewish communities around the world is coloured in sinister shades. The struggle of ordinary Jewish people is denied.

At the Jewish Museum London, the context is provided, and the fact is separated from the fiction.

Jews, Money, Myth is at the Jewish Museum London, 129-131 Albert Street, until 7 July.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.