Leicester, Ugandan Asians and the creation of the 'model minority'

Recalling his childhood spent in the Ugandan capital Kampala, Muhammad Amin says all he has left are memories.

“I had many friends,” the 60-year-old electrician, who now lives in London, tells Middle East Eye, continuing: “Muslims, Sikhs, Hindus, we would walk to school together and after school we’d play together in the street and not go in until we were called for our supper.

“Often we’d just eat at each other's homes.”

Amin’s grandparents left their home in the Indian district of Bharuch in 1943, as part of a wave of South Asian migrants relocating to Uganda - also a British-ruled territory.

Indian migration to Britain’s African territories had been ongoing since the late 1800s, with many moving as indentured labourers and others as merchants and administrators.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Migration from India to Africa began long before the British occupation of both regions, although British rule accelerated the process.

In Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, the Indian presence in Africa is placed as early as the first century, with monsoon winds helping traders carrying goods from further east to cross the seas.

There was also mention of Indian trading posts along the East African coastline in the writings of 15th-century explorer Vasco da Gama, and accounts by Admiral Hayreddin Barbarossa, head of the Ottoman naval fleet.

Today, African countries like South Africa and Kenya are still home to large Asian diasporas, including people from both contemporary India and Pakistan.

They include the current British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, whose mother was born in Tanzania and father in Kenya.

Former British Home Secretary Priti Patel is also a child of Gujarati-Ugandans.

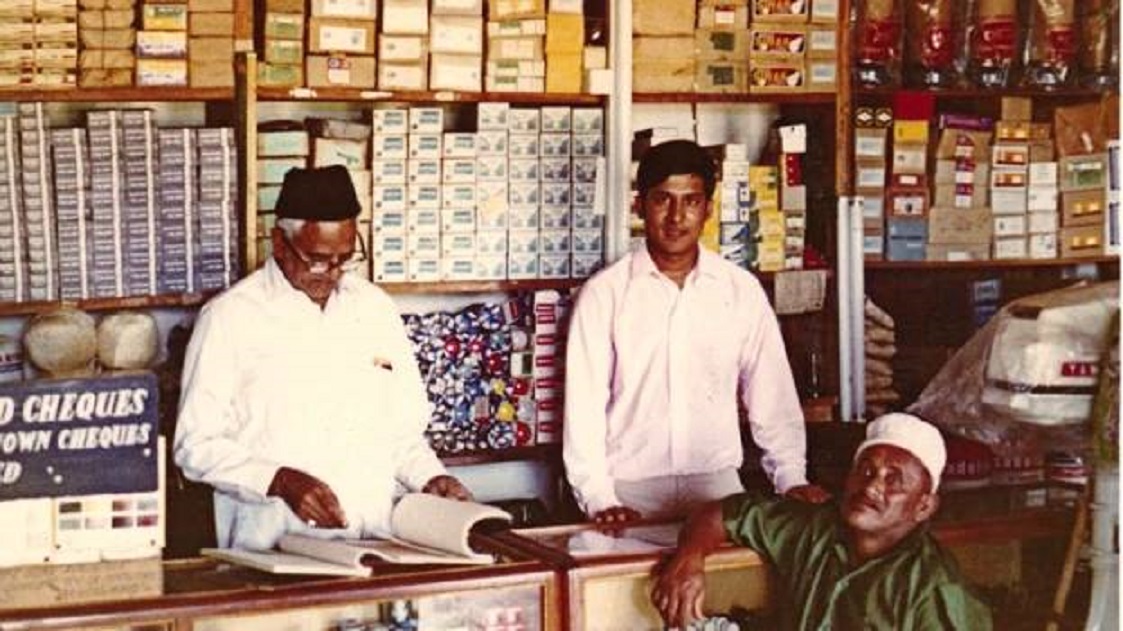

African-Asians were known for their entrepreneurial know-how and often set up shops, factories and other businesses in their new countries.

The Gujarati community, in particular, both Hindus and Muslims alike, were known for their business acumen and described as having an “inner gift for innovation and entrepreneurship” by Gujarati social historian Makrand Mehta.

In the early 20th century, they set up shop as dukanwallahs, which means “shopkeepers” in several South Asian languages.

Asian grocery stores and cafes served African customers, as well as those who came from the subcontinent.

Amin’s own family owned a chain of businesses in Kampala, including a refrigeration company, which afforded them a comfortable lifestyle.

That was until 1972.

The expulsion

At 11-years-old, Amin remembers listening in on panicked conversations between community elders.

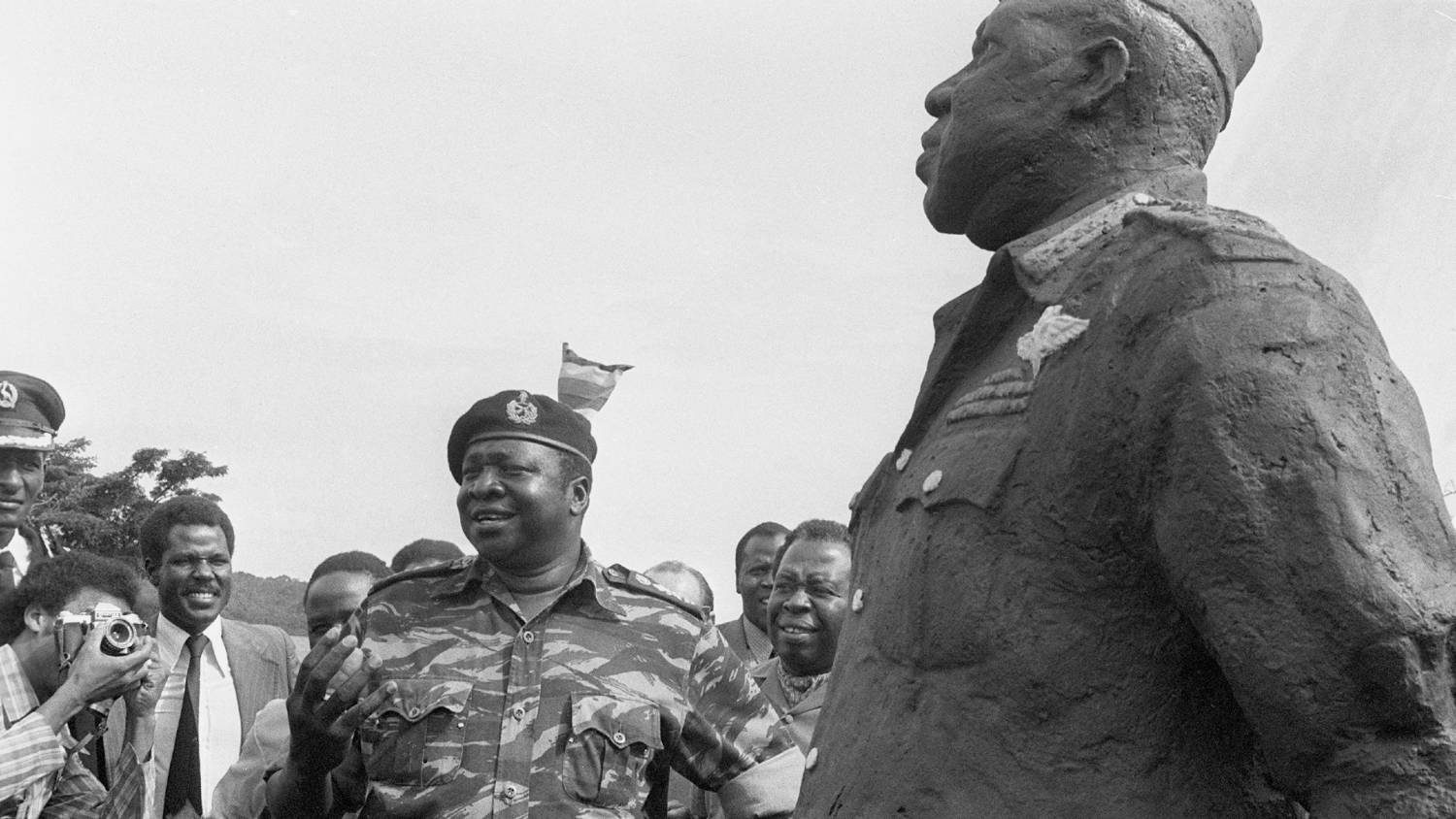

Uganda’s ruler Idi Amin had found a convenient scapegoat for the country’s economic ills in the form of the Asian community, who he openly accused of exploiting indigenous Africans.

However, Uganda’s Asians had been in a precarious situation for decades prior to Amin's decision to expel them from Uganda.

British rule across its empire had weakened as a result of the Second World War and, by the 1960s, newly independent African states were getting rid of the remnants of colonial rule in a process known as Africanisation.

By then the Asian communities in countries, such as Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Malawi, had grown to several hundred thousand.

They lived largely separate lives from their African neighbours and their economic success, as well as their proximity to their former British overlords, made them susceptible to nationalist anger.

Provoking an exodus of Asians was also a way for Idi Amin to exert pressure on British officials who had taken issue with his abuses and maverick approach to governance.

Most East African Asians had left India and Pakistan while those countries were still part of the British Empire. As a result, they retained British nationality and the UK was their refuge of choice. The Indian government, for its part, wanted no role in the matter.

Amin was aware of rising anti-immigrant sentiment in the UK and sending Ugandan Asians to its doorstep would help stoke tensions there.

In 1972, he played his hand, setting a 90-day deadline for Uganda's 80,000-strong South Asian community to leave for "sabotaging the economy of this country".

The exiles found themselves between three countries that did not want them.

In 1968, the British parliament passed the UK Commonwealth Immigration Act, which was explicitly created to exclude East African Asians on racial grounds.

This was also the period when Conservative politician Enoch Powell was prophesying “rivers of blood” brought about by immigration.

Speaking of the Ugandan-Asians, the hero of Britain’s anti-immigrant right, declared: “Their so-called British passports do not entitle them to enter Britain.”

Nevertheless, faced with the embarrassment of leaving British nationals to their fate, 27,000 were allowed to enter through a quota system. Canada took some Ugandan-Asians, as did the United States and Germany.

“I didn’t realise just what was going on until me and my brothers and sisters got on a plane with our parents… and landed in London.”

Amin’s family joined thousands of families arriving in Britain with few possessions and facing an uncertain fate.

In the following decades, Asians from other African states also made their way to the UK fearing a repeat of events in Uganda.

Uganda memories

In a reversal of fate, Jaffer Kapasi is today the honorary consul general of Uganda to the UK, having been appointed by the Ugandan government in 2015. He is also a Gujarati community leader in the Midlands city of Leicester.

His story reflects that of many other Ugandan-Asians who left their homes in central Africa with nothing and rebuilt new lives in the UK.

"I was 18 years old and at college when the announcement was made," recalls Kapasi in a phone interview with Middle East Eye.

"At first we didn't believe it, we thought it was a joke. There were around 80,000 Asians living there, they controlled commerce and trade.

“My father refused to leave, until he saw friends being arrested, and realised Idi Amin was a mad man."

Raised near Masindi on Uganda’s western border, he fondly remembers using lanterns to light up his home that did not have electricity and gazing up at the full moon over the banks of Uganda’s Lake Albert.

“Standing on our veranda, we’d be able to see hippos throwing water on each other. That would be the scene from our back garden,” he recalls.

The son of a successful dukanwallah, his family lived comfortably despite the absence of amenities in the early years, such as electricity.

"The quality of life there was excellent, and that's what we miss the most."

His father, Akberali Allibhai Kapasi, started with a small store, which sold everything from chocolate bars to petrol, but later expanded his business eventually ending up with a chain of shops.

"He worked hard, he had business acumen and was able to make a name for himself, and he employed good honest people to work for him,” Kapasi says, remembering his father.

'We knew there were demonstrations against us coming, the National Front were active at that time. We didn't know where we'd be housed, or schooled'

- Jaffer Kapasi, honorary consul general of Uganda

Bound by common ties of language and business ethics, the Gujarati community worked together, overlooking religious or caste differences, becoming business leaders and traders in plywood, cotton, tea and sugar.

With the expulsion came the loss of those businesses and possessions, but what they retained was arguably just as important.

The Kapasi family, as well as others in the Asian community, retained their business ethic and sense of community solidarity in the UK.

In Britain, many members of the community clustered in certain areas, such as Leicester, which now has one of the largest Asian communities in the UK as a proportion of the total population.

In their new homes, the recently arrived communities set up businesses serving each other, with new cafes and shops catering to South Asian tastes, and later expanded into industries, such as the textile industry.

The community also sought to take advantage of the educational opportunities their new home had to offer.

In the younger Kapasi’s case, this route took him into accounting, a field in which he has his own practice.

Encountering racism

But life in the UK was not all “rainbows and roses”. Besides the destitution they experienced, the Ugandan-Asians also faced a hostile reception amongst many British people.

Kapasi summarises: “We knew there were demonstrations against us coming, the National Front were active at that time. We didn't know where we'd be housed, or schooled, there was a lot of strain, especially for my parents."

An unwelcoming Leicester City Council, fearful of more foreigners arriving to a city that had already become home to a post-Second World War Indian community, went to great lengths to limit a new influx.

When Idi Amin ordered Asians to leave Uganda today in 1972, Leicester Council placed an advert in the Uganda Argus, telling them not to come to Leicester.

— KeyserSosse (@KeyserSosse) August 4, 2020

Had quite the reverse affect didn't it ?👇 pic.twitter.com/CbeCTuCmHl

It took out an advertisement in the Uganda Argus stating: "Present conditions in the city are very different from those met by earlier settlers… thousands of families on the housing list… hundreds of children awaiting places in schools… [social and health services] stretched to the limit."

Kapasi remembers the advert and, in an ironic twist, admits it helped decide his family’s choice of home.

Since the council had mentioned its existing Asian community, his father decided to head to Leicester, where they would be able to access food, speak their language, and practice their culture and faith.

Others settled in London's Harrow and Wembley boroughs, like Amin’s family.

Reviving Leicester

Former UK Prime Minister David Cameron once described Indians and Asians from Uganda as “one of the most successful groups of immigrants anywhere in the history of the world”.

Those who left Uganda were only allowed to take with them £55 (UK sterling), which was around $140 in 1972.

In cities like Leicester, some either set up fledgling businesses from the assets they had managed to retain, while others sought to secure employment, often in manual unskilled roles, such as in textile factories or in companies like Imperial Typewriters, which was based in the city.

By saving enough, they were able to set up their own businesses, transforming the city’s fortunes and preventing it from the fate experienced by other post-industrial cities, such as those in northern England.

In the Leicester of the 1970s, the traditional industries of hosiery and shoe manufacturing were crumbling and most of the machinery used in the large factories was inoperable. Those who could took over the factories and found ways to recycle the machinery to allow manufacturing to continue.

The commercial successes that followed opened up opportunities for other industries, including restaurateurs and clothes shops.

Large parts of the city, once derelict, such as the northern Belgrave area, became bustling retail centres, packed with jewellery shops, restaurants and fabric stores.

In the 50 years since Leicester became home to thousands of Ugandans, it has also become the poster city for multicultural Britain. It has the largest Diwali celebrations outside of India, and is also home to numerous mosques, Hindu temples, and Sikh gurdwaras, as well as synagogues, Buddhist and Jain centres.

Though recent violence in the cosmopolitan city made headlines this summer poisoning communal relations, for the old guard within Leicester’s Asian community, their shared struggle was enough of a uniting factor to deter communalism.

Kapasi says such religious discord is anathema to the city’s residents.

"We’ve lived here for nearly 50 years, there's been complete harmony.

“There are Christian Gujaratis, Hindus and Muslims of different sects, there has been peace and harmony.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.