Liverpool Arab Arts Festival celebrates its 20th anniversary

Earlier this month, vocalist Walead Ben Selim opened his performance to a small but packed audience inside Liverpool’s Philharmonic Hall with a nonchalant statement: “If you want to dance, join us.”

It did not take long for the rapt audience to rise and sway to the rhythm of the tunes as they rose to a crescendo, blending rap, electronica, and old and contemporary Arabic poetry. It was also not the first time the 38-year-old Moroccan musician, who sports an enormous afro, had mesmerised his crowd: his debut at the Liverpool Arab Arts Festival (LAAF) came in March 2020, when the event was forced to move online as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. The festival’s organisers were impressed with his 45-minute set, to a backdrop of the mountains of southern France.

Bringing in people from all over the UK, and internationally, this year’s festival was curated around the theme A Point of Connection - Nuqtat Wasl in Arabic, which is fitting, at a time when people are yearning to connect after almost three years of pandemic lockdowns, social distancing and masks.

This year, the festival marked its 2oth anniversary, and ran from 7-17 July in different venues and spaces throughout Liverpool. As well as the opening concert, it included contemporary dance, artistic workshops, exhibitions, poetry, spoken word, storytelling sessions (podcasts), as well as the launch of a new bilingual publication of poetry from diasporic Yemeni communities in the UK. And it culminated with a family day event.

History of the festival

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Taher Qassim, co-founder of the festival, hails from Yemen but has resided in the city for over 25 years. Registered first as a charity in 1998, LAAF holds various art events throughout the year and operates primarily through its educational programmes.

“We started with tiny projects in schools where our own children went, and then we got invited to other schools,” Qassim said. As his initiative picked up momentum, he began organising parties where he included Arabic music, and sometimes Irish music, too.

Despite a nativistic turn in British and international politics, he says Arab immigration to the UK has a rich history. From as early as the end of the 19th century, Yemenis and Somalis first began fleeing their countries for the UK, some making their way to Liverpool. When the British protectorate disintegrated in Aden, Yemen in 1967, a huge wave of Yemenis followed. Later, at the turn of the 21st century, with invasions, wars, revolutions and crackdowns dominating the Middle East landscape, larger and more diverse communities followed suit.

Over the years, the festival has continued to grow in size and number of attendees, many of whom are interested in learning more about the different events and cultural elements from the region.

Images, words and rhythms

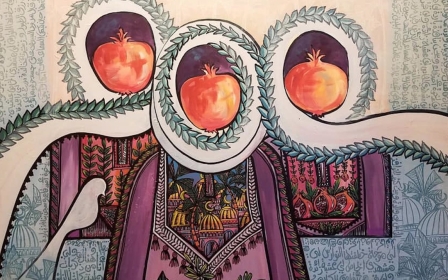

Photos are a powerful tool to connect people. Although the festival’s theme speaks to a world trying to physically bond after a pandemic, its ethos is perhaps best encapsulated in its collaborative approach. One example is the exhibition between Arab Image Foundation and Beirut Printmaking Studio.

Founded in 1997, Arab Image Foundation is custodian to 500,000 photographic objects from the Arab world. For the exhibition, 19 residents from Beirut’s Printmaking Studio selected images from their special collections, spanning the 1870s to the 1970s. The artists then responded by creating intaglio prints, displaying the positive prints of the original photographic negatives alongside a diptych.

"The wonderful thing about working with LAAF was this freedom to manoeuvre,” Heba Hage-Felder, director of Arab Image Foundation, told MEE. “We also gave the artists carte blanche, the liberty to explore and look at the collections and choose what negatives they wanted to work with.”

The exhibition was held at Liverpool John Moores University’s Exhibition Research Lab at the School of Art and Design, which perfectly aligned with Hage-Felder’s goals of seeking to inspire a younger audience and to showcase how two disciplines interact to create new interpretations around photographic images. It featured alongside a new video commission by emerging British-Algerian artist Hannaa Hamdache.

Mike Pinnington, a writer and editor based in Liverpool, attended the exhibition and was impressed. “They're both doing different things, obviously, but often speaking to the same experience - of migrants, of dealing with cultural and historical contexts. I'm glad to have seen both - the festival does a job of platforming communities rarely given consideration in the UK beyond the usual barbed questions of belonging in a predominantly white society."

Yemen in Conflict

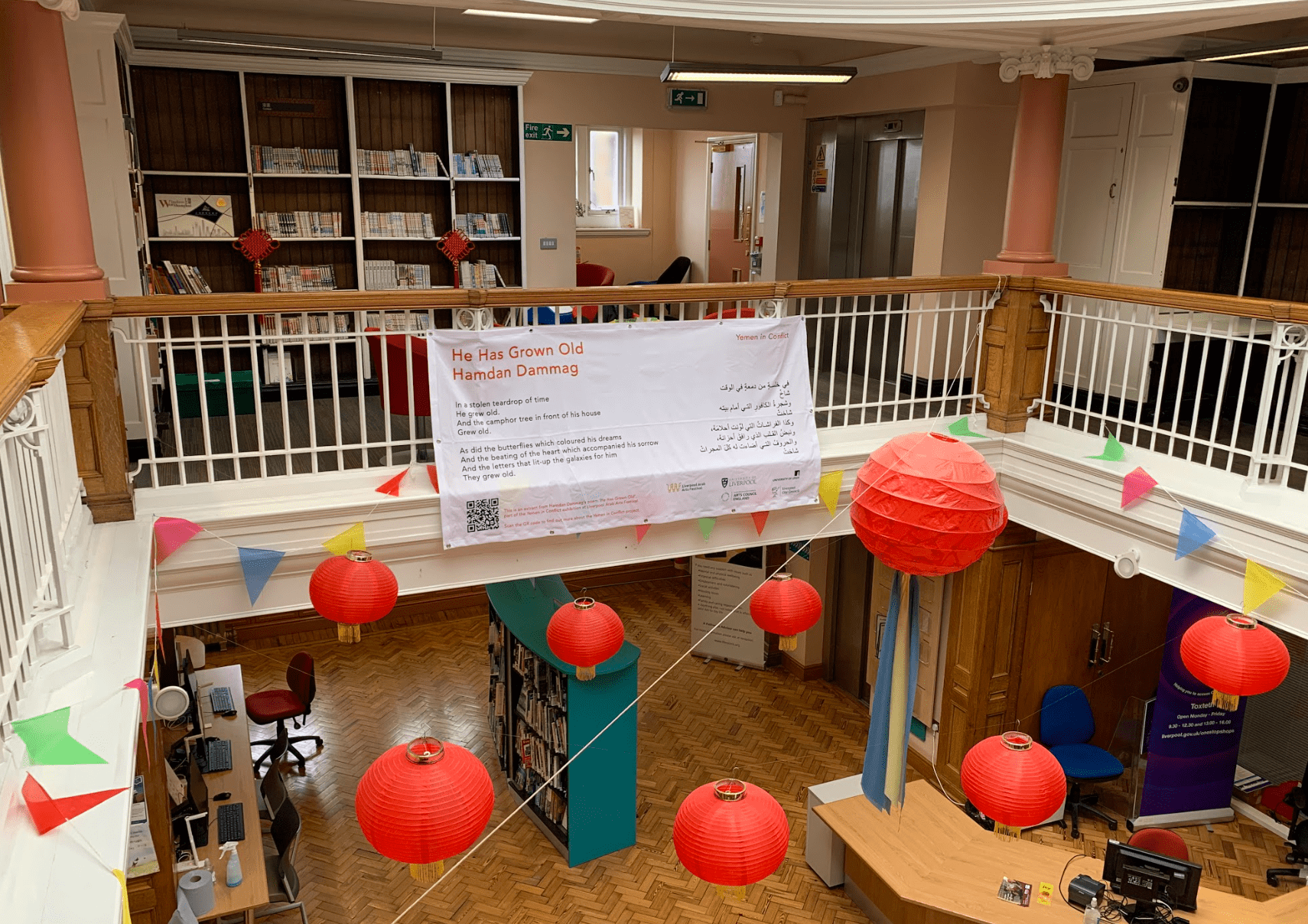

Another major project that looked at connection was Yemen in Conflict, an ongoing collaboration between Liverpool Arab Arts Festival, the University of Liverpool and the University of Leeds, which probes how storytelling might bolster both political and public awareness of the situation in Yemen. Literature, as always, accompanied the programme.

On one of the festival days, the Merseyside Yemeni Community Association brought people together to celebrate the launch of a Yemen in Conflict book, a new publication of poetry from the Yemen in Conflict project. The location chosen was a site that has strong community resonance, as opposed to only organising events in the city centre, which can sometimes create a barrier.

Additionally, on that same day, Comma Press provided a sneak preview of Egypt +100, a new anthology exploring the events of the 2011 Tahrir Square revolution through the lens of science fiction. Speaking about it together were Egyptian writers Mansoura Ez-Eldin and Ahmed El-Fakharany, with one of their English translators, Paul Starkey.

For those who were not able to attend in person, there were digital ways to experience some of the vibrant events through a podcast titled ARTISTS/IDEAS/NOW and a virtual talk with A.MAL, an art and research initiative featuring a group of young female artists based between Morocco and the UK, who presented their work on family archives in an engaging conversation that resonated with the work of Arab Image Foundation.

'It’s our favourite festival, and we love Liverpool, a small city of warmth, cosyness and beautiful architecture'

- Louai Alhenawi, composer

The pulse of the festival, however, returns to music. The renowned London Syrian Ensemble, a stunning collective of eight musicians and graduates from Syria’s renowned Damascus Conservatoire, revealed their new project, Sounds of Syria, a dynamic and emotional response to the recent diasporic experience caused by revolution, war and upheaval.

Composer and Ney soloist Louai Alhenawi has performed at LAAF before.

“We love LAAF, it’s our favourite festival, and we love Liverpool, a small city of warmth, cosyness and beautiful architecture.”

Food, crafts, music and family

Traditionally held on the final Sunday of the festival, Family Day is a chance for everyone to gather in the heart of the city, over food, craft, stories and music.

Ending the festival on a high was the Hawiyya Dance Company, who brought a unique blend of Dabke and contemporary dance and took the stage alongside the El-Funoun Palestinian Dance Troupe. The groups put on a spectacular and high-energy performance, in addition to TootArd, a trailblazing duo from the Golan Heights, Aar Maanta, young Somalis described as "the voice of our generation", Ali Al-Jamri’s children’s dollhouse project and more.

Al-Jamri, a poet and English teacher, described how the theme of the festival, and the way it allowed people to connect, was what stood out the most to him.

“What is the Arabic that all children can access? All children, no matter their degree in Arabic, can ask their mother: ‘When will dinner be ready?’ Or ‘I’m hungry, feed me,’” he explained.

From here arose the al-Usra wal-Sufra project, where children wrote poems in both languages, which will be on display next to a doll's house created by locally based multidisciplinary artist Rosie Stanley.

“In the same way that many of us created our homes in these English houses and build them up in the Arab way, we took this typically English doll's house and remodelled it so that inside it is an Arab’s home,” Al-Jamri said.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.