Lost words: The struggle to save Turkey's disappearing languages

To reach her home, Ms Vaic, a 90-year-old woman from Turkey’s northeast Black Sea region, must climb a steep hill to the village of Xigoba, where she lives in a traditional wooden house.

Here in the hills of Hopa, the traditional language spoken by the people is Homshetsi. It is one of many endangered languages in the country and speaking it is dear to Ms Vaic’s heart.

'The teachers did not like it when we spoke Homshetsi'

- Ms Vaic, 90

She tells Middle East Eye that she counts on traditions such as holiday gatherings to help it survive. In Turkish, her village is called Basoba and it is that name you see depicted on road signs.

With her daughter-in-law helping to translate from Homshetsi to Turkish, Ms Vaic says she also learned Turkish in school, where speaking her native language was prohibited.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“The teachers did not like it when we spoke Homshetsi. They would ask us to open our palms and act like they would hit [them] with the ruler if we spoke. They didn’t hit us though.”

The Homshetsi are one of Turkey’s minority ethnic groups, alongside the Armenians, Arabs, Kurds, Circassians and Zazas who help make up Turkey’s current population of just over 80 million.

The republic has come a long way since the 1980 coup, when the constitution was designed to ban the public use of minority languages. Still, the damage done in those dark days makes the task of protecting these ethnic tongues much harder, members of three minority groups told Middle East Eye.

The next generation of Homshetsi, Laz and Syriac people of Turkey may not be able to speak their mother tongues, according to UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, which classifies three languages in the country as extinct and 15 more as endangered.

This is a region that has been home to countless peoples and cultures for thousands of years.

Grassroots efforts such as holding weekly chat sessions or publishing chronicles are necessary, but they fall short of ensuring the long-term protection of the Homshetsi language, according to Harun Aksu from the northeastern Artvin province.

Living about 20km from the Georgian border, Aksu is the author of the Homshetsi-Turkish dictionary, which contains 2,500 root words.

“Language is culture, language is identity. If our native language is not spoken by the future generations, then the identity will die along with it,” Aksu said.

In only two decades, the dictionary author says, the language he shared with his parents and grandparents may fade away, mainly due to urbanisation and unsupportive state policies.

Nomadic culture

Numbers are vague as to how many native speakers there are in Turkey, but some 100-150,000 are believed to speak Homshetsi, an archaic western Armenian dialect also spoken in western Georgia, Russia and parts of Armenia, where the group migrated from two centuries ago.

Nomadic by culture, the Homshetsi people live in the evergreen hills of northeastern Turkey and widely make a living through breeding livestock, selling tea, wood, butter, milk, and yogurt. While women traditionally work harder and longer than men, it is up to all native speakers today to help their mother tongue survive.

“On Saturdays, we speak only Homshetsi at home. My son even writes poems in Homshetsi,” Aksu said proudly.

Remembering his younger days, Aksu said anyone who spoke Homshetsi at school in the 1980s was punished. “The teachers would force spicy paste in our mouths".

The tie between the Armenian - thus Christian - identity and the Homshetsi culture is one reason why the group has been ostracised, according to the activist, although the Homshetsi in Turkey widely identify themselves as Muslims.

'I wish the Turkish government would put the Homshetsi language as a mandatory lesson'

- Harun Aksu, author Homshetsi-Turkish dictionary

Turkey’s linguists and academics are not courageous enough to seriously research the language due to this historic connection to Armenia, argues Aksu, adding that there is a “sly pressure” on the Homshetsi people in their social lives as well.

This pressure, Aksu believes, is rooted in Ankara’s “Turkification” and “assimilation” policies targeting the country’s many minority identities, starting with the foundation of the modern Turkish state in 1923 and stiffened through the 1980 coup.

“I learned Turkish in school. So, did I become Turkish the day I learned Turkish?” Aksu asked.

“The national student oath forced us to say that our existence should be gifted to the Turkish existence. Only when I grew up did I understand what that implies,” he added.

The pledge of allegiance was removed under the conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) administration in 2013, sparking a backlash of criticism from secularists and nationalists in Turkey.

“Nationalists still ask me if I love Erivan," Aksu says, referring to the former homeland of his people, before the creation of Turkey. "But I have no particular sympathy for it. My homeland is Turkey, it’s Hopa".

Saying the Homshetsi are happy to live in Turkey and fulfil their military duties, Aksu said the Netherlands, where Dutch is the official language and a spectrum of minority languages are under state protection, is a great example for what he wishes to see here.

“I wish my language was protected by state measures, and not by UNESCO. I wish the Turkish government would put the Homshetsi language as a mandatory lesson in the curriculum where we live, and teach it like it teaches English. The situation today makes me very sad".

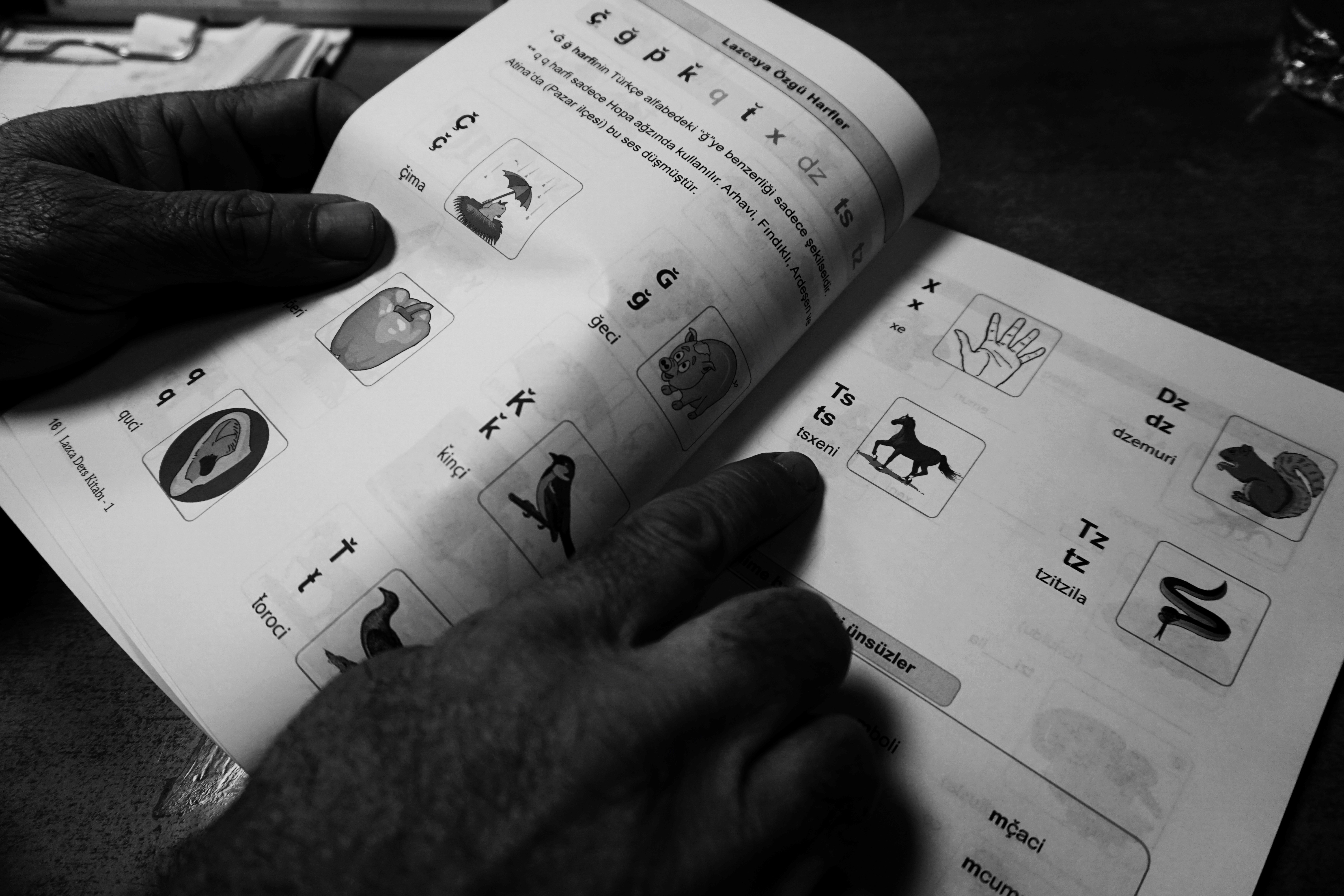

The Laz people and their language

Also living in Turkey’s northeastern Black Sea region, Turkey’s third largest minority ethnic group, the Laz people share a similar past and anxiety for their cultural future.

While their existence as a minority group is much more widely acknowledged than the existence of Homshetsis across Turkey, the Laz language is similarly marked as “definitely endangered” by UNESCO.

There are at least 1.7 million ethnic Laz citizens across the country, according to official statistics in 2011, and there are few associations devoted to preserving and teaching the language.

Birol Topaloglu, a nationally famous Laz musician, has been a leading figure voicing frustration against Ankara’s language policies for years.

He sings folk songs in both Laz and Turkish and plays the tulum, a bagpipe-like instrument, as well as the kemence and chogur, both string instruments. The village home he lives in is, like the instruments he plays, steeped in the culture of his people.

“I built this stone guesthouse from scratch when I heard that they were planning to erect a house of cement here,” he said, showing the land he bought in Artvin’s Arhavi county, his motherland.

Unlike his past routine in Istanbul, here in Artvin the musician brews tea off the branch in the early morning and cooks the traditional black cabbage he grows in the garden. “I want my culture and language to exist in the future. If the traditional home is not preserved, these values cannot survive either,” he said.

Saying the Laz language is still “indirectly banned” in Turkey, the situation breaks Topaloglu's heart. “The law seems like it allows it, but the dynamics won’t, and that’s because of the government’s old ‘one language, one flag’ policy,” he said.

'Parents are afraid learning Laz will harm their children’s accents when speaking Turkish'

- Osman Safak Buyuklu, Laz textbook author

Teachers would punish him by forcing him to stand on one foot when he spoke Laz in elementary school, he noted, looking back.

Now, a few state schools in the area offer elective Laz classes, following a “democratisation” policy installed in 2013, which foresees similar opportunities for a few other minority languages including Kurdish, Adyghe and Abkhaz in certain regions.

Ankara’s move is welcome but seen as insufficient after years of ignoring demands coming from its ethnic minorities, with the primary request standing as the right to education in mother languages.

At this point, mandatory lessons in state schools where Laz people traditionally live is the only way to avoid language extinction, according to Osman Safak Buyuklu, author of numerous Laz textbooks and publications.

“[Parents] do not prefer their children to take the elective courses,” he said, sitting in his office at a gas station in Arhavi, drinking tea collected and dried nearby. “They do not see it as a profitable skill like learning English is... They are afraid learning Laz will harm their children’s accents when speaking Turkish and fear it may hurt their careers,” he added.

Noting that it was the popular and late folk-rock singer Kazim Koyuncu who helped break a certain level of prejudice against the “caricaturing of the Laz accent in Turkey,” Buyuklu explained that his mother tongue is comparatively tough to pronounce.

“Our accents are made fun of, but the reasons behind that remain unspoken. We have a lot of consonants in one word and use vowels differently. So, we can’t make certain sounds when speaking Turkish,” Buyuklu said.

“The truth is, many people in Turkey are not even aware that Laz is a language on its own, or that the kingdom of Lazica existed in this region centuries ago".

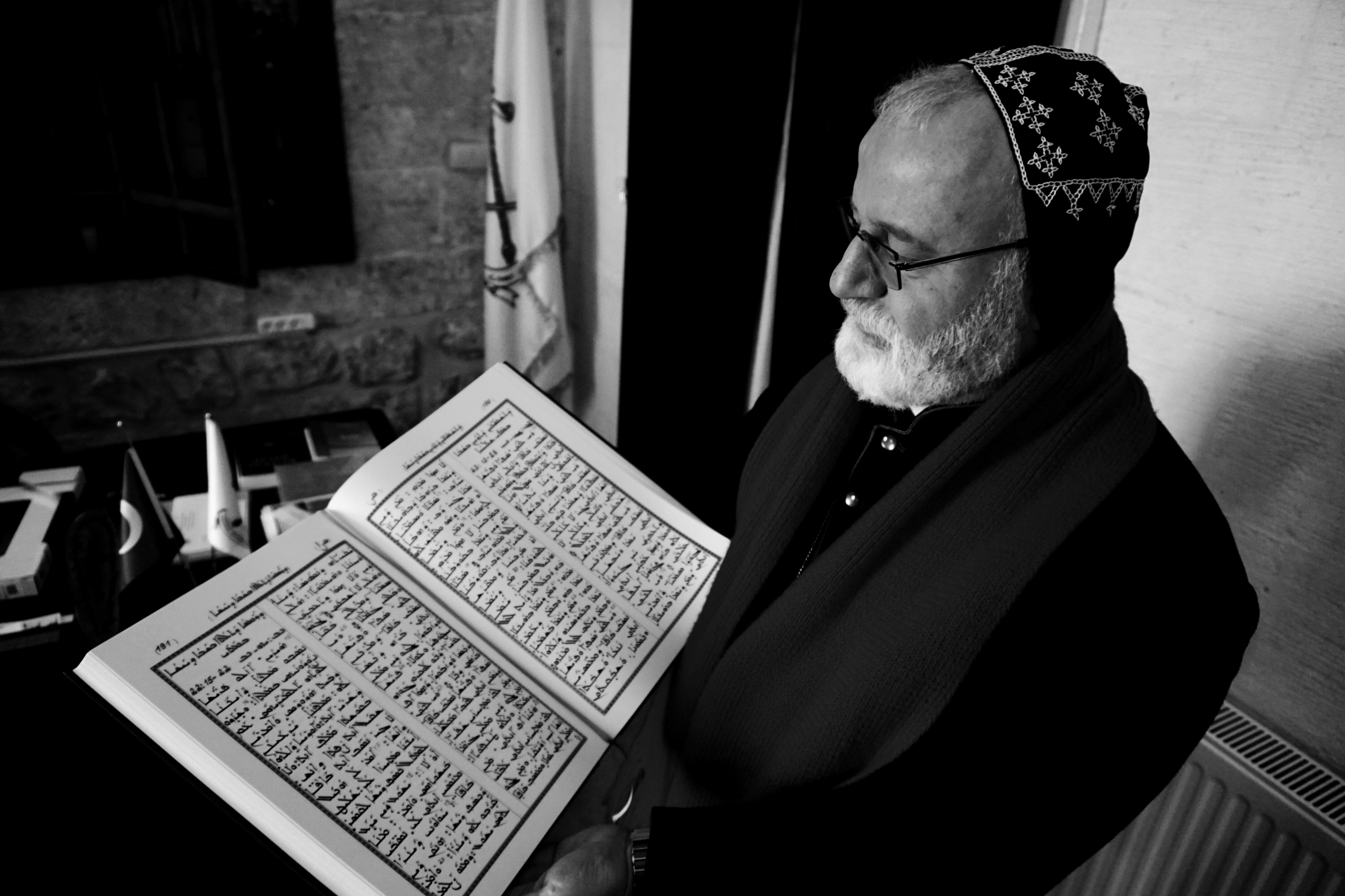

Syriac: ancient lingua franca

Members of another ethnic minority are eager to get a similar message out. The Syriac Orthodox community’s homeland covers a number of Turkey’s desert provinces by the Syrian border, some 600km south of the eastern Black Sea region.

There are around 70 Syriac families in the southeastern Mardin province’s city centre, Abot Gabriel Akkurt, Patriarch of the Deyrulzafaran Monastery, said. Some others live in villages in the outskirts, where their mother tongue is better preserved according to the patriarch.

“Syriac is ancient, one of the oldest languages in the world,” Abot Akkurt said. “We may be a minority today, but we were already here when other civilisations arrived.

“This land has always belonged to the Syriac,” he added.

According to Abot Akkurt, the Middle Aramaic language was the dominant tongue across the Middle East for centuries, especially from the 4th century on. “Everyone spoke Syriac back in the day. It was like what English today is".

“That is why this language matters for the whole of humanity. Since then it remains almost unchanged from its original version, those who can speak and write Syriac can easily read artefacts from millennia ago,” he said.

According to the patriarch, Syriac will be able to continue to protect its own existence, as the community will keep going to church, where prayers are made in their mother tongue – although churchgoers rarely know and speak the language.

That is because monasteries are the only facilities where a Syriac Orthodox citizen can learn his or her mother language in Turkey, Aydin Alkan, a 19-year-old guide at the Deyrulzafaran Monastery said. He is one of those few, and said he is still hopeful his language will carry on without support from the Turkish government.

Living inside the “Saffron Monastery,” there are a few students, two patriarchs and staff workers. Funds come not from the Turkish government, but from Syriac communities in Turkey and around the world.

Syriacs are famous for their homemade wine and double roasted coffee, and nowadays they make money selling the cultural brand to tourists in the city centre.

“I love living here, but we’ve been assimilated,” one churchgoer, Deniz Kirilmaz said, referring to her city where it is ordinary for a local to speak four regional languages fluently.

“I just really wish I could understand our Syriac, and make prayers knowingly,” she added.

MEE asked the Turkish government for comment, but had not heard back by the time of publication.

This article is available on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.