Middle East cinema: Why you can't watch some of its best films

For cinema audiences beyond the region, the Middle East and North Africa is rarely regarded as a hotspot for genres such as science-fiction, comedy, fantasy and horror.

Unlike other non-English areas – say Scandinavia, South Korea or even Bollywood - Arab movie exports to international festivals and cinemas are usually socially realistic dramas, hybrid documentaries and experimental art films.

Often such films add to the one-note view of the Middle East as a war-infested zone only abundant with refugees and immigrants.

Conversely, it's rare that such films dent the box-office in the Middle East, where comedies are usually the most popular and bankable genre in MENA, just as they are the world over. Rarely does a festival breakout hit such as Nadine Labaki’s Oscar-nominated drama Capernaum attract local audiences.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

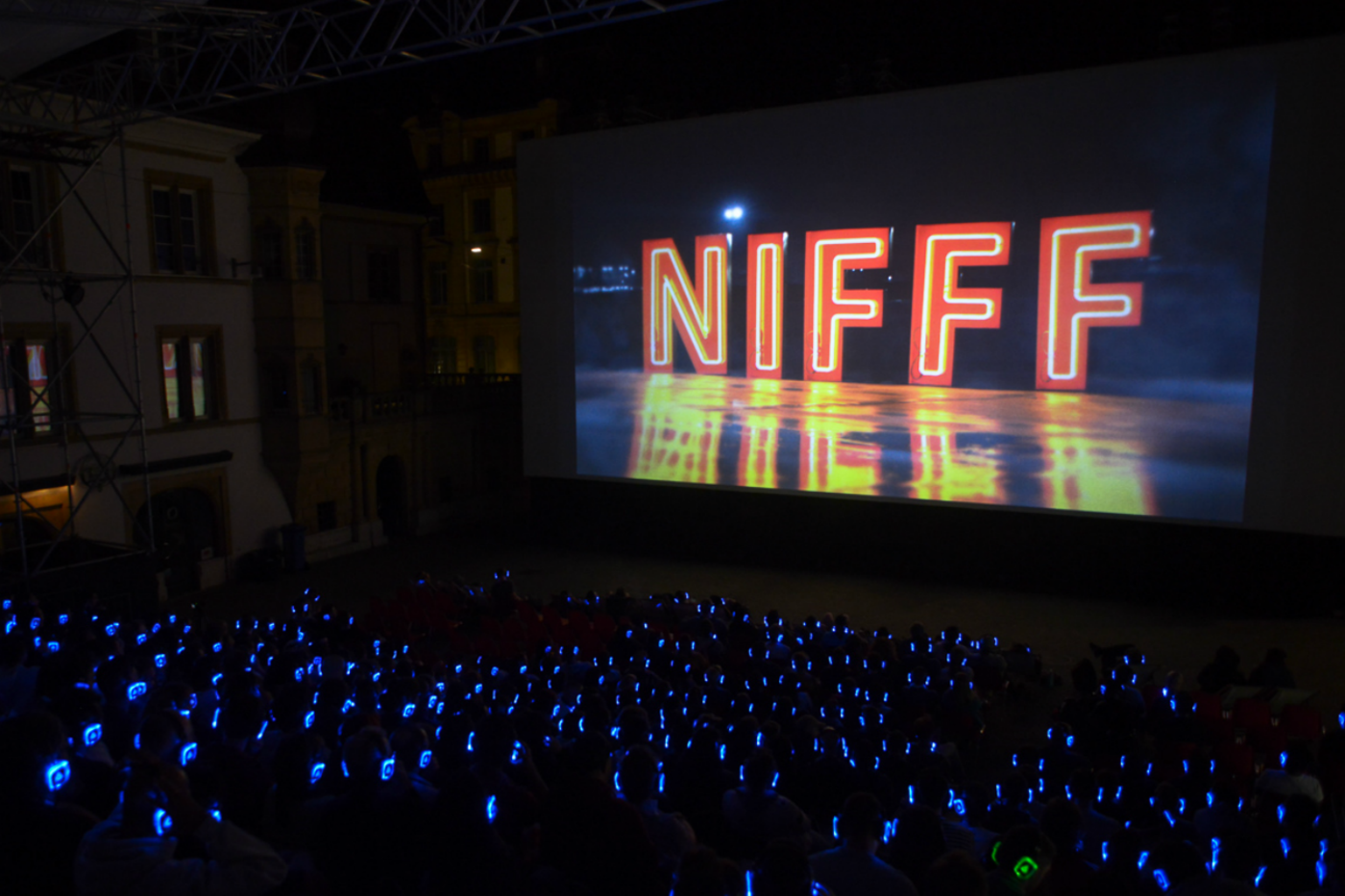

Anais Emery, artistic director at the Neuchâtel International Fantastic Film Festival (NIFFF), which focuses on genre films, told MEE: “People are now interested to see fiction from the Middle East, and not just the news. Fiction is a good tool for expressing our fears and desires, and thus, knowing more about the other.”

Genre in the Middle East: Ignored by festivals

The notion of “genre films” is a fluid one – typically it refers to features that share common themes or narratives, be they thriller, science-fiction or western. Often they feature common conventions (such as the car chase in a thriller) or characters (the sidekick in a comedy). More recently the term "genre" has come to refer to science fiction, fantasy and horror (festivals more accurately describe this grouping as “fantasy”).

Genre films have been the bread and butter of Egyptian cinema, the region’s chief producer, since its golden heyday of the 1930s. But while the classics of thriller master Kamal El Sheikh - such as Life or Death (Hayat Ou Maut, 1955) and The Last Night (Al-Laylah al-Akheera, 1964) - did travel at the time, the vast majority of the country’s rich and highly diverse genre cinema still remains unknown outside the Arab world.

The midnight sections of most major film festivals – often reserved for genre movies - opt for American, French or Asian fare rather than that from the Middle East.

Rare titles do make the cut such as Babak Anvari’s Under The Shadow, an Iran-Iraq war horror drama that owes a debt to Henry James’s story The Turn of The Screw. But to do so they need foreign backing (Under The Shadow is a British co-production) or the seal of approval from a western institution (it premiered in Sundance) or include elements traditionally associated with MENA (here, conflict between two neighbouring countries). Otherwise, Middle Eastern genre features are too casually dismissed or disregarded altogether.

A growing number of Middle Eastern productions have tried to challenge the reigning dichotomy of art-house versus mainstream, with critically praised genre films that range from crime dramas and thrillers to outright horror and fantasy.

Recent features and thrillers have marked a breakthrough in both technical attributes and narrative sophistication, such as Marwan Hamed's Egyptian film The Blue Elephant (El Fil El Azrak, 2014), about a medical professional who comes across an old friend in a psychiatric hospital for criminals; and Rattle The Cage (Zinzana, 2015), from the United Arab Emirates, in which a prisoner's fate depends on a sadistic cop.

But overall the results are artistically patchy, highlighting the continuing challenges for Middle East film-makers, including lack of finance, mainstream audiences unwilling to embrace unconventional films and that bias towards social dramas.

Is genre getting the platform it deserves?

Festivals devoted to genre films - known as fantastic festivals - have been a growing fixture on global film circuits for several years, but often remain unexplored by Middle Eastern cineastes.

The likes of the Neuchatel International Fantastic Film Festival, which began at the turn of the millennium, are challenging this gap in knowledge with the diversity and boldness of their programming. Held in Switzerland in July, it has grown into one of the most important forums for thrillers, horror, fantasy and sci-fi films.

It deserves plaudits for its left-of-field programming and marquee guests – including Jean Dujardin (The Artist) and Takashi Miike (Audition, Ichi the Killer) – who draw a young enthusiastic audience. But most important of all is its forward-thinking programming and initiatives that all pinpoint the future of genre filmmaking.

This year’s symposiums included the impact of gaming on society; stereoscopy as a precursor of fantastic cinema; and, most intriguingly, a discussion with computer-generated actors. There was also Reflections of Sub-Saharan Africa, an eye-catching retrospective of African genre cinema - the first of its kind at a festival.

NIFFF has evolved into a hub for exploring the past, present and future of genre film-making. For audiences, the experience can be eye-opening; for the industry, it’s a crash course in how to produce different types of genre-driven stories.

It is also increasingly frequented by also Middle Eastern film-makers. This year, three very different films from the region used different forms to inspect political issues, thereby illustrating how genre features are an elastic and creative way to circumvent state censorship.

With Abou Leila, Algerian director Amin Sidi-Boumedine turned the sparse Saharan backdrop into a Lynchian hallucinatory nightmare about the violent legacy of the Algerian civil war.

Moroccan newcomer Talal Selhami took a leaf out of the Gremlins storybook for Achoura, an American-flavoured coming-of-age horror tale, set during Ashura, that explores the lingering trauma of the Maghreb’s authoritarian rule.

And Danish-Iraqi Ulaa Salim examined the rising anti-immigrant sentiment in Europe in the futuristic thriller Sons of Denmark.

“Diversity has always been one of the main objectives of the fest from its inception,” Emery told MEE. “From the start, we wanted to break the traditional notions of ‘fantastic’ to include art-house; to have a broader geographical representation; and to increase participation of LGBT films.

“The notion of programming art-house and fantastic side by side seemed inconceivable to many 20 years ago. And now, if you look at the Cannes competition for example, this has become the norm.”

To underline Emery's point, Cannes this year included Jim Jarmusch’s zombie feature The Dead Don’t Die, Won-Tae Lee’s The Gangster, the Cop and the Devil from South Korea; and Lorcan Finnegan’s social fantasy Vivarium.

Middle East film industry doesn't help

But in the Middle East, festivals continue to focus on predictable social dramas and ignore genre, despite their duty to represent and enrich regional film culture of all genres.

The handful of genre features that do qualify either have to have attracted heavy critical buzz, or to have previously played major festivals. There is no room in the Middle East for the small, unorthodox genre films on the fringes.

Nor is is there any commercial incentive for the Middle Eastern film industry to promote such films. Often producers will not push a release internationally if it has already been a success in the region: foreign markets are a luxury, not a necessity.

When this writer programmed The Pool (2014), a Danish horror film at the Cairo Film Festival in 2014, it was the first of its kind – and an event that proved to be a sizeable attraction. But that was the exception.

This absence of a progressive culture in part explains the challenges that have beset Beirut’s under-funded Maskoon Fantastic Film Fest, the region’s sole genre film festival, which holds its fourth edition later this year.

It was founded by producer Myriam Sassine and script supervisor Antoine Waked of leading Lebanese production house Abbout ("maskoon" means haunted in Arabic). It has garnered critical acclaim and international recognition for its adventurous programming and engaging symposiums.

Yet it has struggled to attract a large audience in a city that remains culturally segregated. It also suffered two of its films being banned by the authorities: Gaspar Noe's hugely acclaimed Climax; and Nocturnal Deconstruction, a short by young Lebanese film-maker Laura El Alam.

Attendance in 2018 was up, Sassine told Middle East Eye last year, despite apathy of many cinemagoers: "The Lebanese audience wants to see the film they've already heard about. They have little penchant for discovery. They've become lazy. Having films from Cannes surely boosted the attendance this year."

Part of this cinematic division is rooted in what Emery describes as the “dominant white Caucasian culture” of the 1980s, which originated in the US but has moved on to shape cinemagoing habits globally. This, she says, cemented the now-prevalent view of audiences and the industry that “genre” is only about sci-fi, horror and action.

“If you look back at the history of cinema, the notion of the fantastic had a different connotation,” says. “There are long and rich traditions of the fantastic that goes back to the early silent work of [ground-breaking French director] Georges Melies."

In a 20-year period during the late 20th century, Emery says, the idea of what was a “fantastic” film was reduced to a stereotyped - and it is this that “genre” is now identified with. But she sees hope for the future.

“With the new technology, there has been an increasing conflation between different genres. Fantastic can be anything now. Film-makers are no longer confined to one type of genre; the leap or transition to the fantastic is cheaper and more flexible now. Fantastic is probably the most dynamic form of cinema at the moment.”

Yet swathes of genre-driven Middle Eastern films continue to pass under the radar internationally. Part of the reason, Emery stresses, is the lack of representation at international festivals and markets like NIFFF.

“We don’t get a lot of proposals from the Middle East,” she said. “If they don’t have important producers, sales agents or major festival representation, we don’t know how we’d see these films.”

Sassine told MEE in 2018 how Maskoon is run by volunteers and with very limited financial support. “Every year, I have to assemble the finances from scratch. Every year I wonder if we're going to make the festival happen.”

Hope for the future

Amid this vacuum, several directors in the region have attempted to bridge the gap between genre and arthouse with both previous and upcoming work.

Iran's Shahram Mokri has crafted an inventively unconventional marriage between theatre, literature and slasher flicks in horror comedy the Fish & Cat (2013); and vampire flick Invasion (2018). Tunisia had its first horror hit with Abdelhamid Bouchnak’s Dachra, inspired by The Blair Witch Project.

And a new wave of dystopian thrillers is emerging in Turkey including Orcun Behram’s Bina, or Night Bulletin (in which a government broadcast menaces its citizens); Can Evrenol’s Girl With No Mouth (disfigured children on the run from the brutish authorities); and Erdem Tepegoz’s In The Shadows (a world populated only by the working class and controlled by unseen forces).

The inclusion of Scales, Saudi Arabia's Shahad Ameen’s debut mermaid-themed feature, in the forthcoming Venice Critics’ Week, is a testament to the proliferation of the independent Middle Eastern genre film.

Other festivals, aside from NIFFF, have awoken to the region's potential. In 2017, Austin’s Fantastic Fest programmed a sidebar cheekily titled “Yalla, habibi” (which translates as “C’mon baby”), showcasing lesser-known genre efforts from the Middle East.

Among the highlights were two atypical entries from Egypt: Fangs (Aynab, 1981), a brilliantly kitschy remake of The Rocky Horror Picture Show; and The Originals (Al Asleyeen, 2017), a satire that blends social commentary with mystery and espionage.

'Directors should continue to experiment, digging into their own experiences or those of the people around them'

- Evrim Ersoy, creative director, Fantastic Fest

Both films proved to be major hits. Amy Nicholson of IndieWire wrote at the time: "The success of Yalla, Habibi dismantled a long-held misconception: that mainstream Middle Eastern genre movies don’t travel or translate abroad."

Evrim Ersoy, Fantastic Fest’s creative director, says: “The Middle East has always been distinguished for its rich traditions of storytelling, and I’ve always been curious about how the region’s genre cinema would look like in a modern setting."

Support for genre-filmmaking is still missing, he agrees: there is no desire within the regional industry to nurture and develop fantasy talents.

But there are positives.

“On the technical side, there has been a lot of improvement. Structure-wise, the film-makers are still in the free-wheeling form phase. They’re at that stage when they’re still trying to find their own voice, in coalescing their different influences into unified structures.

"Directors should continue to experiment, digging into their own experiences or the experiences of the people around them.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.